A 5,000-Year-Old Trace in Midin

To make wine in Tur Abdin is to carry the memory of the land into the present. Lucas Barınç brings Midin’s ancient traditions into dialogue with the textures of the modern world.

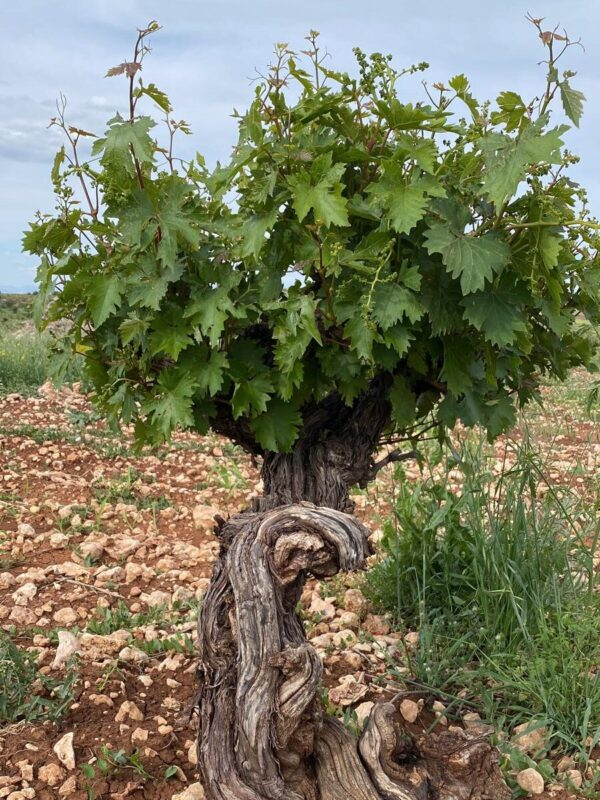

Between the Euphrates and the Tigris stretches a geography shaped by the footsteps of countless civilizations: Tur Abdin. On the map, you see rugged cliffs, sun-baked slopes, blistering summer heat, and endless stone terraces cascading into one another. Yet in the eyes of Lucas Barınç, another landscape comes into focus: vines that split stone as they search for water, vineyards 80, 120, even 150 years old, and a winemaking effort that has persisted stubbornly for millennia in this hot, arid land.

Lucas does not see himself as an entrepreneur chasing big dreams, but simply as “a man running a village winery.” That humility has seeped into every bottle produced in Midin. Here, wine is not about modern machinery, glossy branding, or polished marketing lines. It is about preserving the memory of the soil, keeping step with the rhythm of village life, and building a living bridge between past and present. Lucas grew up surrounded by grapes carried home on donkeys, games played among stone piles, and summer vines reaching skyward under a merciless sun. So even now, as he manages a winery, he says, “I’m not telling you anything new. This is simply the life we know.”

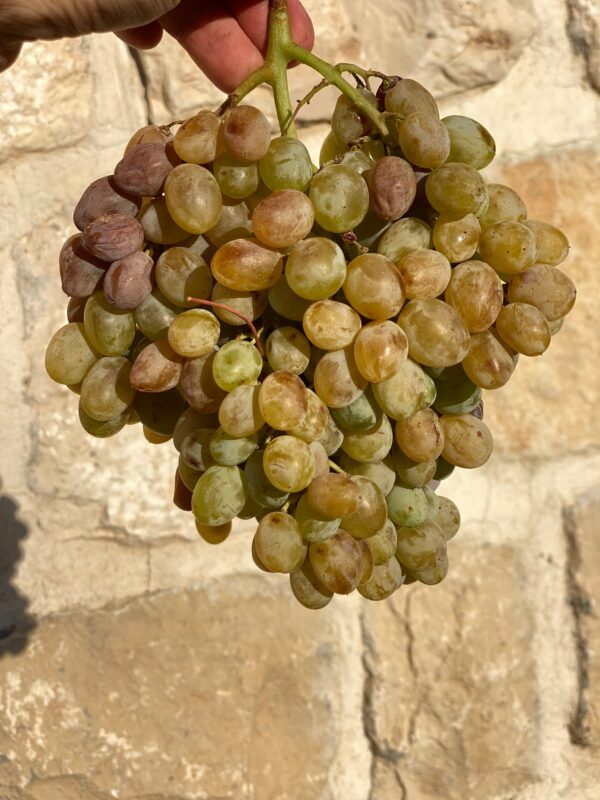

The story of Midin Winery carries two immense forces on its shoulders: the pressure of the climate crisis and the legacy of a culture shaped by religion, tradition, neighborliness, and migration. Local grape varieties—Kıttıl Nafs, Raşe Gurnık, Gavdoni, Bılbızeki, and Karkuş—are reclaiming value after standing on the brink of disappearance. Some were historically used for church wine, some for molasses, and some simply because they were delicious. The Midin Winery family sees these not as items on a “rediscovery list,” but as responsibilities handed down through generations.

In this interview, Lucas Barınç talks about how heat amplifies aroma, how old vines “speak,” and the risky magic behind natural fermentation. But above all, he explains why wine here more than a beverage is. Because in Midin, grapes are more stubborn than people. Because wine is the oldest memory flowing through the veins of a culture. Because in these lands, each harvest is a ritual—a whisper that the past is still alive.

Lucas’s words carry both the weight of a weary landscape and the joy of a people who hold their ground with unyielding determination. Midin Winery thrives at that very intersection. And today, each glass offers not just flavor, but a thousand-year-old story.

Inheriting a family legacy in viticulture dating back to 1525… What kind of weight and motivation does this create for you, technically and emotionally?

We’ve been doing viticulture for 5,000 years. This region —north of the Euphrates and Tigris— is the center of viticulture in the world. Considering the climate was once cooler than it is today, this was the most ideal place for growing grapes. Honestly, we don’t see it as an emotional burden or inheritance. We simply do what we love.

How do the 80–150-year-old vines in Midin make a technical difference? What do you observe regarding root depth, water access, low yield, and aroma intensity?

I don’t know exactly how old vines make a technical difference, but looking at them is spiritually nourishing. The low yields today are mostly due to climate change —rising temperatures and insufficient rainfall. What we do know is that the roots travel deep, breaking through the rock to reach moisture. In a way, the vine renews itself, but all that searching exhausts it, and eventually it stops producing fruit. As for aroma, I think we should ask our winemaker, Saba Açıkgöz.

Let’s greet your winemaker, the esteemed Saba Açıkgöz, one of Turkey’s notable figures in oenology. Lucas, could you elaborate on the oenological traits of local varieties such as Kıttıl Nafs, Raşe Gurnık, Gavdoni, Bılbızeki, and Karkuş? What potential does each one carry?

Kıttıl Nafs is mostly grown in Şırnak’s Uludere region on high terraces; the lowest vineyard is at 1,400 meters. According to the people of Şırnak, it’s the most delicious grape in the world —but in our opinion, it’s simply a wine grape. We tease them: they think that because they haven’t seen any grape other than Kıttıl Nafs. The Assyrians made wine only from this variety.

Raşe Gurnık and Gavdoni were grown for church wine. Msabık is an early-ripening grape. It’s technically a wine grape, but since it ripens early, families planted only a few vines each. We will increase that planting. Bılbızeki is purely a table grape —sweet, sour, acidic, aromatic… It has everything. Karkuş is different. It’s not for the table; it’s only suitable for wine and molasses. Still, it is the main grape of the Tur Abdin plateau because it’s hardy, grows anywhere, and rarely gets sick. The plateau stretches from Kızıltepe in the west to Cizre in the east, and from Nusaybin in the south to Gercüş in the north.

Midin’s terroir is strong: high heat, drought, stony soil, and old vines. What fundamental identity does this terroir give to the wine? How do you achieve balance in acidity, tannin, and alcohol?

Making wine from our vineyards has never been easy. We can barely get proper yields anymore. Vineyards take 10–15 years after planting to produce good grapes. A 30-year-old vineyard is an adolescent; a 50-year-old is still considered young.

Heat itself is not the issue —as long as we get the winter snow and rain we used to. Our vineyards are accustomed to heat. But after the dams were built nearby, the humidity started to affect us negatively. They create rainless, gloomy clouds in summer— weather we never had before. And when the suffocating August heat lasts for two weeks, it dries out not only the plants but the people as well.

Heat enhances aroma. Yes, tannins are high, acidity is normal, and high-alcohol wines can easily be made. We try to maintain balance. Sometimes we miss the alcohol balance in whites. Grapes can gain 5 brix in just one week. And when that week coincides with Syriac religious holidays—no one harvests. So the sugar shoots up all at once.

Using natural yeast in fermentation is a very bold choice. How does this spontaneous fermentation give the wine its character? What are the challenges?

We use yeast only for Öküzgözü. It is natural yeast, of course, but we still supplement it. Öküzgözü is the most challenging grape for us to ferment. If the Brix level is high, fermentation stalls; if it’s low, fermentation rushes too quickly and the wine loses balance. We struggle to find the right middle ground. Other grapes, however, require no added yeast. If you restrain Boğazkere, it refuses to ferment; Karkuş needs no intervention whatsoever. Choosing not to add yeast is a significant risk—complications can appear even after fermentation ends.

The viticultural culture of Eastern and Southeastern Anatolia —especially the Syriac tradition—seems to have forged a sacred bond with wine. How do you carry this culture, both technically and emotionally?

Wine runs in our veins. It’s intertwined with life here. We encounter wine almost from the week we are born. And with such abundance of grapes, people naturally feel compelled to transform them into something. Villagers usually make wine from the surplus. They make molasses, dried grapes, fruit leather, sweet almond paste —but still, grapes remain. So what do you do? You make wine.

How would you describe the style of your wines? Is it the intensity of a ‘warm climate,’ or the refined aromatic structure that comes from old vines?

We make wine entirely according to our own taste. We imitate no one. We try to remain who we are. And honestly, I don’t think anyone else should try to be like us. Our wines are full-bodied because that’s how we prefer to drink them. We never sell a wine we ourselves would not enjoy.

Names like Cehennem Deresi (Hell Creek) are more than brands; they carry the story of the land. What cultural, historical, and emotional layers influence your naming process?

Our wines, our brand, and our labels must reflect our character. We are independent and free-spirited to the core. Ours is a difficult geography, shaped by struggles over identity and religion. For this reason, we try to distance ourselves from the past as much as possible. Yet we grew up with stories, and we love bringing those stories to life. They inevitably find their way into our wines.

What techniques do you use in vineyard management —summer pruning, stress management, irrigation strategies, disease risk? Do you have any practices unique to Midin?

We do not prune in summer or winter; we prune in spring. We never irrigate —there is no way to do so anyway. The vineyards are old, fragmented, and dispersed. They are divided into a thousand pieces with different owners. Modern viticulture is impossible here. New investments are extremely costly. Wine is expensive enough as it is. Although we know when the vines may fall ill, villagers do not apply pesticides. Everything is left to fate. Because of drought, yields are low, and there is no real economic return.

Which technical process has been the most challenging for you in winemaking?

Fermentation, stabilization, bottling, oxidation risk… Fermentation is our biggest challenge because we harvest late. Cold weather sets in, and while almost every winery in Turkey is shutting down for the year, we are just beginning with Boğazkere. Sometimes malolactic fermentation doesn’t finish until spring. Stabilization is easier for us —we do cold stabilization in winter. By opening all the facility doors, we can chill unbottled wine down to 4 degrees. In short, we benefit from the winter cold.

How is your professional relationship with the local community shaped? Has a “Midin ecosystem” emerged?

We are a village winery. Although we are a family-run, commercial business, at heart we function as a social project that provides a significant service to the village. Whenever we need help, the entire village rushes in. When the village needs something, we drop everything and help. We have not made a profit yet —and perhaps we never will— but we are content with our role.

Do you have any series where you experiment with oxidation? Or do you prioritize fresh fruitiness? How do you decide on your stylistic approach?

We produce 50–60 thousand liters of wine, so we must create wines that are non-oxidative and durable. We use minimal sulfur and prioritize aroma. We also try to filter as little as possible.

Does Midin have plans to move toward wine tourism? Do you intend to introduce the region’s cultural heritage, gastronomy, and vineyards to visitors?

As a company, we have no grand ambitions of expanding or becoming a regional focal point. Over time, people hear our story; the more they drink, the more they appreciate our wines. Promotion helps, but a good wine from a small winery will always find its audience. We have no plans to step into gastronomy, but we would like to offer local bread, cheeses, and nuts to our guests.

What is the most emotional moment for you in the vineyard —harvest mornings, the taste of a grape, or a story told by an elder?

Stories move us deeply. Here, pain always sits at the forefront. Even when we try to forget and look ahead, it remains important for people to know their history. History always lights the way.

I’m curious about your distribution network and professional goals. Are you targeting local, national, or international markets?

Our dream is to market half of our wines abroad. Whether this is feasible under current economic conditions, I’m not sure. There are distributors willing to export our wines, but the distributor we choose must believe in us and share our worldview. Within Turkey, we work with Global Wines, owned by Nadiya Bıçakçı, particularly in Istanbul. Locally, since we are a small operation, we don’t need a broad distribution network. We aim to increase sales through Istanbul Airport duty free.

Where do you see Midin five years from now? In terms of tank capacity, team, analytical infrastructure, and cultural heritage, what is your plan for the future?

Who knows what five years will bring… We will not increase capacity; in fact, we will reduce production and prioritize quality and sustainability. We believe output should depend on the harvest. We operate with the mindset of “whatever that year brings.” Preserving heritage isn’t our job —the past will endure as it should. Our burden is already heavy enough with this climate and geography. The economy is unpredictable; crises may also create new opportunities, and we will adapt accordingly. So far, we have never planned for the following year. Our motto is: Work as if there will be no crisis, but be prepared as if you may pack up and leave tomorrow. Mentally, we are ready for anything.

Final question, Lucas… If wine were a person, how would you describe the personality of Midin wines—ancient, rebellious, wise, or all of the above?

I believe it is all of the above. We are a company with deep cultural roots. But above all, I would say our wines are “wise.”