Cem Sağbil on Sculpture, Shifts in Direction, and Mythology

An artistic journey extending from Turkey to Germany… A bond forged through permanence, mythology, and the ancient… Cem Sağbil revisits humanity and time through the deliberate slowness of sculpture.

Sculpture is sometimes a silence carried from one geography to another; at other times, it is the weight of time resting on a shoulder, in a hand, in the body itself. In Cem Sağbil’s universe, sculpture becomes both a physical and conceptual space. On one side lies the technical rigor of bronze; on the other, the unseen layers of mythology.

His artistic path has never followed a straight, continuous line. Instead, it moves through shifts in direction, ruptures, pauses, and a stubborn, deep-rooted progression. It is a journey that began in Turkey, sharpened in Germany, and ultimately returned to Turkey to mature within the fires of bronze casting workshops. Along this journey, concepts such as belonging, body, myth, and mystery matter as much as the idea of permanence.

Today, as his sculptures inhabit public spaces in Paris—merging with a different cultural memory—and as he brings Anatolia’s ancient goddesses into the rhythm of the contemporary world, Sağbil constructs a slow and persistent artistic language in an age defined by speed. Perhaps for this very reason, sculpture remains a form of thinking for him—one of the clearest ways to speak with time, with people, and with memory.

When and how did sculpture first enter your life? When you look back, is there a moment when you thought, “This is where my direction changed”?

Looking back, yes—there have been several turning points, several dramatic shifts in the direction of my artistic life. The first happened in my first year of high school. I received a slap from my art teacher because he didn’t like my painting. He was the only one who disliked it. I didn’t paint again until I finished high school; it was my form of protest.

I failed algebra and geometry and had to repeat a year. During that period, I took the university entrance exam and scored well, but still didn’t get a placement. None of my choices included an art department anyway. Meanwhile, the Fındıklı Academy of Fine Arts had opened applications, and you needed to take an aptitude exam. I took the exam with the hope of living a bit more freely—and I passed.

But since I couldn’t graduate due to failing two courses, I took private lessons at a family’s home, sat for the high school completion exams two months later, and that same night went to Istanbul to attend the Academy. That family played a monumental role in my life. The two months of intense studying, and the care and respect they showed me, gave me tremendous momentum both personally and artistically.

After studying at the Fındıklı Academy in Istanbul for three years, I went to Germany, where I studied sculpture and ceramics for seven years. That was another major turning point. Later, I completed four years of bronze training—another dramatic shift. I then opened a bronze workshop in Izmir. Five or six years later, I opened another one in Istanbul. I closed my workshop in Germany in 2013. Yes, when you lay it all out like this, my path has changed direction many times.

Your artistic journey began in Turkey and deepened in Germany. How did working in another country reshape your relationship with sculpture?

Even though I was somewhat familiar with Western culture, not being fluent in German naturally affected my social relationships at first. The academic system was very different; opportunities were better, working conditions more civilized… I remember thinking, “No one here seems to have any problems.” Most people worked abstractly—installations, performances—and video art was becoming dominant.

I think minorities hold on more tightly to their traditions to preserve a sense of belonging. While trying to understand my environment, I began creating mother goddess statues—Cybele figures. Over time I evolved; different materials and more philosophical topics entered my field of interest. But eventually, figurative work became the mode of expression I loved most.

Your education spans interior architecture, design, and ceramics. Do you see sculpture at their intersection, or as something independent?

Each of these disciplines is important on its own, and I truly enjoyed working in them during my training. But in time they begin to merge, and you stop drawing boundaries. In a sculpture you create, you might see a small design detail or an element borrowed from interior architecture. You begin to look at the bigger picture. I think they merge and form a synthesis.

Bronze is central to your practice. Do you remember your first encounter with it? How did your relationship with the material begin?

Early on, I was preoccupied with permanence. I tried many materials, but bronze ultimately gave me the answer I was seeking. My friend once asked me to cast in bronze the first Cybele sculpture I made for his father. It was an exciting request. I hurried back to the Academy and studied bronze casting for four more years with a teacher I deeply respected.

Today, that dear friend Boğaç Sebük, his father Yalçın Sebük, and my esteemed teacher Boris Grünwald are no longer alive. But that bronze Cybele statue remains. Now I ask myself: how valuable is this permanence? I no longer know…

Establishing your own bronze casting workshop is a major step. Was it born out of a desire for independence, or was it a necessity?

Normally, it’s rare for an artist—especially a sculptor—to own a bronze casting workshop because it is an entirely technical operation. I had been commissioned to create bronze sculptures for a project in Turkey, and I planned to cast them in Germany and bring them over. But deadlines didn’t match, and the costs were too high. Thanks to a close friend, I had the opportunity to set up a workshop in Izmir. The workshop I founded in 1999 still casts my sculptures. I trained a devoted team, and they have now become even more skillful than I am.

Mythology is a key reference in your work. Is mythology a source of stories for you, or a lens through which you interpret the present?

This is the first time I’ve heard the term “repository of stories.” I prefer to call them stories or legends—they feel more mystical, more mysterious. They open a vast space for me as an artist—a timeless, spaceless realm. Even abstract concepts that resist understanding. It’s like observing our present lives from the summit of a mountain. I create with that feeling. So yes, mythology is both a collection of narratives and a way of making sense of the present.

Your works such as Hemera and The Man Holding the Moon highlight contrasts—night/day, woman/man, East/West. What draws you to duality?

My travels to other countries, especially Western ones, strengthened my sense of duality. My awareness increased over time. Without these opposites, I suppose nothing would fully make sense.

What are the conceptual or formal differences between creating for public spaces and creating for galleries?

Works displayed in galleries or exhibition spaces are generally chosen by us and shown to a small, closed audience. In public spaces, however, you must consider the cultural and political context of the country. Otherwise, you simply cannot place sculptures in public areas.

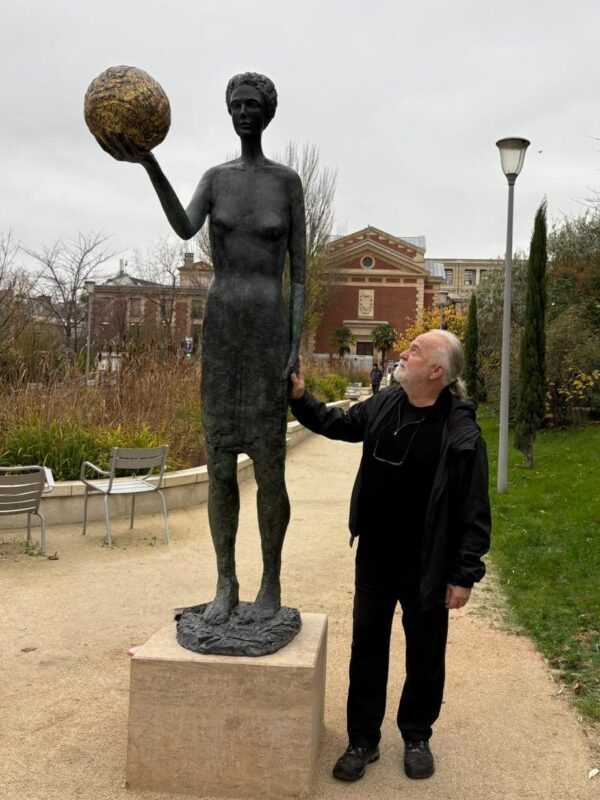

Recently, one of your works was placed in a public space in Paris. What does this mean to you?

It means a great deal. It’s wonderful that my work has been received this way. Now I feel free to make petty stuff as I like.

In a city like Paris, where history and artistic heritage weigh heavily on everyday life, what does it mean for a sculpture to integrate into the urban fabric? Did the reactions of viewers there open up new questions for you?

Yes, the question naturally arises: among more than a thousand sculptures, there are two—“Ay Tutan” and “Hemera.” At first glance, as I mentioned earlier, this feels magnificent to me; but for Parisians, it is a very small nuance within a much larger whole. Yet the truth is this: these two sculptures have earned the right to exist in that atmosphere. And the feedback I have received so far has been very positive.

Do you think that a sculpture becoming part of another country’s cultural memory transforms an artist’s own sense of “belonging”?

I don’t think so; it doesn’t change it. But the concept of belonging can gradually dissolve and fade over time.

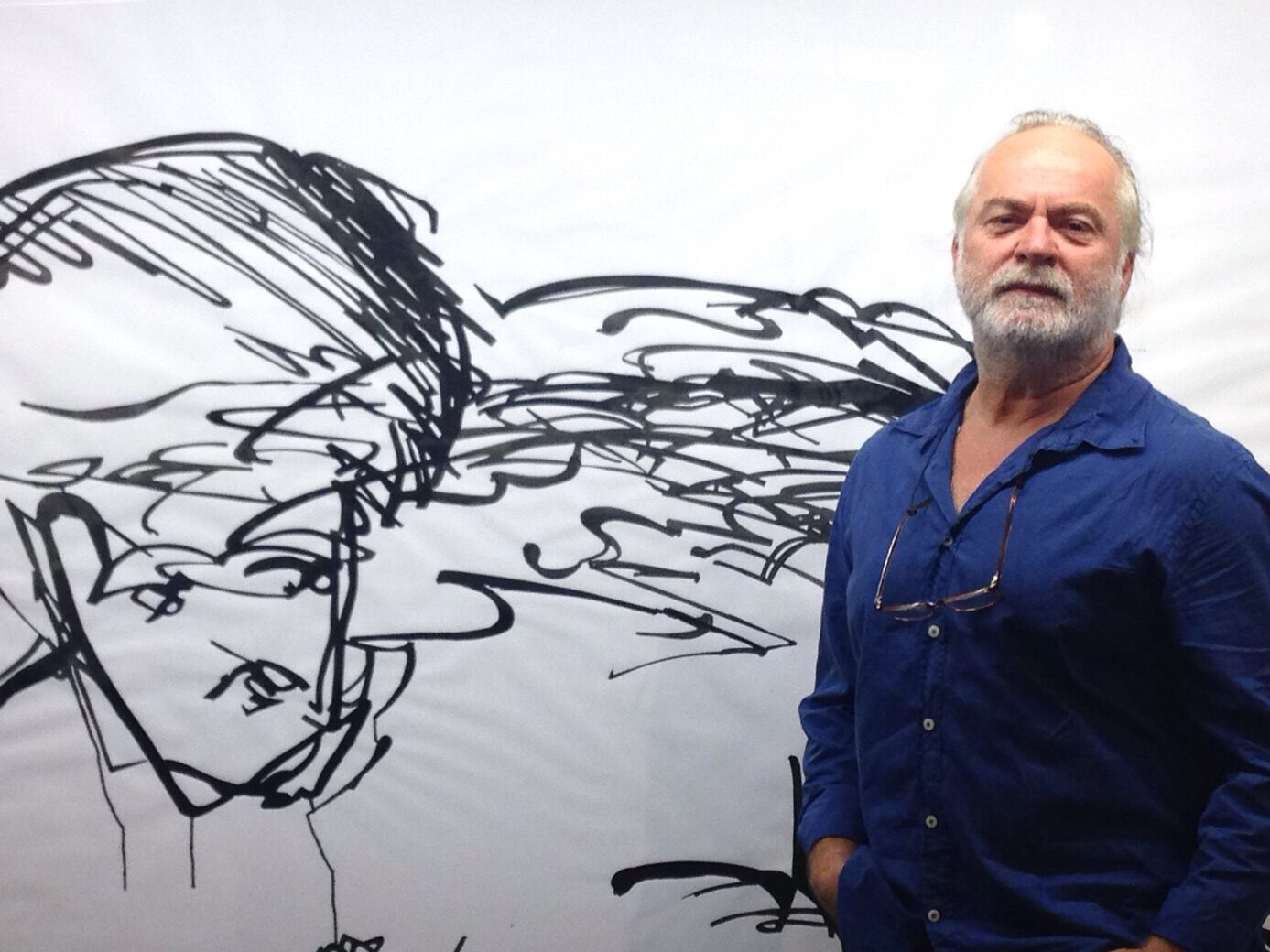

In the “Pouring Out” exhibition, we encounter a deeply personal process—sketches made on plane trips turning into sculptures years later. What do sketches represent for you: a space for thinking, or a kind of inner dialogue?

Under the title “Pouring Out,” the airsickness bags on planes gradually transformed into a long-term project. The starting point was simply wanting to make good use of time spent on flights, especially when there was no paper available for writing or drawing. After filling a certain number of sick bags with daily ideas, planned sculptures, and thoughts, I realized this was becoming a project and continued with enthusiasm. Today, I have more than 700 sick bags collected over nearly 30 years.

You have a sketch archive spanning many years. How do you know when a sketch is saying, “It is time to become a sculpture”?

It’s a very complex process. Sometimes an idea settles, and it quickly becomes a sketch; other times, I start a sculpture and continue sketching while shaping it. But first, the idea must take root in my mind. After that, the process reveals itself.

The female figure and the theme of “Goddesses” have become more visible in your recent works. How has your relationship with the female body, power, and sacredness evolved?

In general, gender has always remained somewhat secondary in my sculptures. But creativity—nature’s creativity—is a concept associated with women since ancient times. It is magical, mysterious. Until the moment men realized they were the ones fertilizing… At that point, the concept of creativity shifted, and some of its magic was lost. Yet I believe this mystery, this sense of magic, still continues.

Anatolia’s ancient cultures and mythological layers are strongly present in your work. Is this geography a conscious reference, or a natural seepage?

In the early 1980s, I had the opportunity to travel around Anatolia. While studying in Germany, at the request of my classmates, I traveled throughout Turkey and acted as their guide. During that period, we visited almost every part of the country. What surprised me most was that every 50 kilometers, we seemed to leap forward or backward 500 to 1,000 years in time. I think such richness is extremely rare in the world—if it exists anywhere at all.

I don’t think one can fully experience or learn about this richness today. Not many people are curious anymore. If tourists don’t come, there is no perceived need—because culture is busy moving backwards every day.

As an artist who has been producing for many years, when you look back, is there a work that still surprises you?

When I see my sculptures in places I haven’t visited for a long time, I feel a slight sense of surprise and pride. I try not to show it too obviously, but it is very enjoyable to see them again.

Sculpture is an intensely physical and laborious form of creation. Were there times when you struggled, even considered giving up? How did you navigate those moments?

There was a period when I had to close the casting workshop for a few months because I had no financial means left. My son was little at the time; he asked me, “Did you go bankrupt?” At that moment, I thought I would only go bankrupt when I died—and a week later, I reopened the workshop.

Of course, there are difficult moments. But I believe thinking positively makes things much easier. And you should not reduce it all to sculpture alone. You also paint, think, write, draw. The palette is rich. So I never see it as a monotonous occupation, and ultimately, everything serves a purpose—the messages you aim to convey.

In today’s world, speed, consumption, and superficiality dominate. What does it mean to exist with a “slow” art form like sculpture?

Yes, we are going through an extremely fast technological era; we feel it everywhere, and we will feel it even more. It is visible in sculpture and in art at large. We have no chance of rejecting these developments. Artificial intelligence is beginning to take over everywhere. But what remains for us is still emotion, still creativity. These will carry us for a while longer. What comes after that, I don’t know.

Do young sculptors consult you often? What fundamental advice would you give to someone starting out today?

When younger artists meet me, they ask questions, they want to learn; I share what I can. But there is one truth: my truths will never be their truths. They have their own truths, their own dreams, their own paths to follow. And at the heart of it all is “curiosity.” They must not lose that.

Technology is advancing at a frightening pace; they need to stay as aware as possible, technologically speaking. Ultimately, emotion still holds an important place within us—as creators, as artists. I walk with these values; I try to convey that every time.

When a sculpture is finished, can you mentally detach yourself from it? Or does each work continue to walk with you?

There have been no breaks in the work I have done throughout my artistic life. Subjects and concepts follow each other in a kind of harmony. There may be very small mutations in between. Usually, while working on one piece, what comes next—even if it is very small—starts taking shape in my mind.

Is there a project you are working on, or nurturing inwardly, one for which you say, “its time has not yet come”?

I have several very serious projects; they are almost fully ready in every detail. I just haven’t had the opportunity to realize them yet. But that doesn’t mean I won’t.

Finally… If someone were looking at your sculptures many years from now, and you wished to be remembered in a single sentence, what would that sentence be?

I think that person will write their own story when they look at my sculptures. I don’t know if it will say anything about me.