Presenting the Forty-Fold History of Baklava

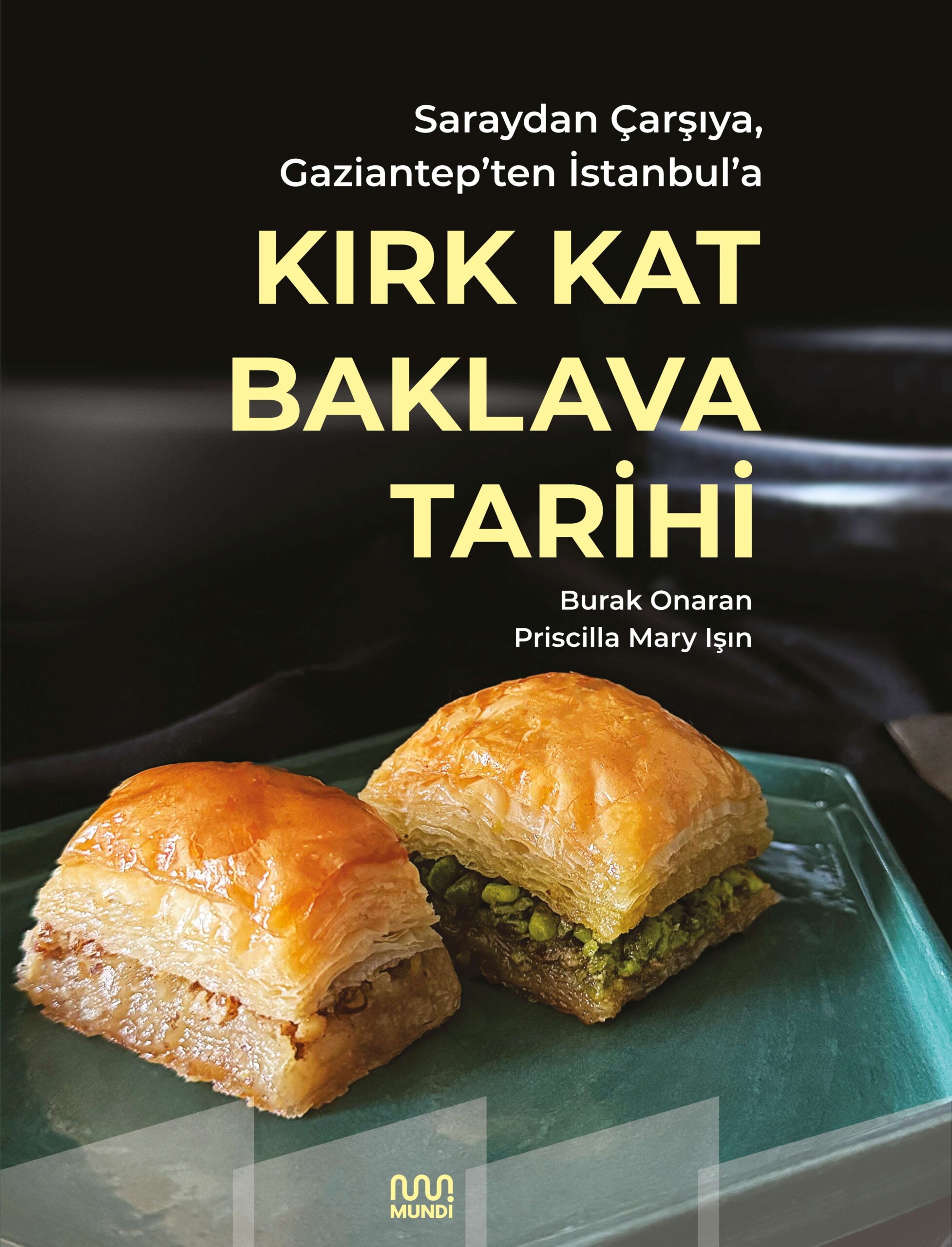

The history of baklava, which has been reflecting the joy of weddings and feasts since Ottoman times, is in Kırk Kat Baklava Tarihi (A Forty-Fold History of Baklava) with mouth-watering visuals. We listened to the story of the book from its authors.

Even though we have left Ramadan behind, we are still fond of baklava, the symbol of the feast. But how much do we know about the history of baklava? Was baklava, which is seen as a symbol of happiness and good times, always made with walnuts or pistachios as it is now? How did the 20th century’s rapid transformations affect baklava production? After more than two years of in-depth research and teamwork, history researchers Burak Onaran and Priscilla Mary Işın, the authors of Palace to Bazaar, Gaziantep to Istanbul: A Forty-Fold History of Baklava, published by Mundi Publications, shared the historical adventure of baklava with Saatolog readers.

How did you get involved with this project and what kind of a division of labor did you do?

Burak Onaran: Murat Güllü from Karaköy Güllüoğlu and Merin Sever, the editor of Can Publishing, who is also very interested in food culture, embarked on this project based on the lack of a deep research on the history of baklava. Then they came to Mary and me. Mary focused mainly on Istanbul and palace cuisine, while I focused on the transformations of baklava over a 120-year period from the beginning of the 20th century to the present day.

Priscilla Mary Işın: I’ve always worked on Ottoman cuisine and baklava is my first love, I’ve been doing this for about 20 years now, but there’s always something new. Baklava is so important that the notes I took were hundreds of pages long. This project allowed me to do a much more detailed work, without summarizing at all, where we can put every detail. In that respect, the offer from the publishing house was very attractive. The history of baklava is a dessert that really deserves a book.

B.O.: When we were formulating the book, we wanted it to be a work of history that would come up to the present day. Historical works on such subjects are often limited to the study of origins; they do not include the recent past. They present a distant and romanticized narrative of the past. This book, on the other hand, starts from the first written mention of baklava and goes all the way up to the present day. We asked Mary to write a comprehensive Ottoman section that would make full use of the sources she had found so far, and then we moved on to the 20th century, when baklava was at its most dynamic. But when we started, we didn’t really know what the recent history of baklava would offer us; we were up for the adventure.

How far back can we take baklava?

P.M.I.: The first person to mention baklava was the folk minstrel Kaygusuz Abdal. Kaygusuz Abdal writes tons of poems, some of them are about food. Of course, they have mystical meanings. I can’t understand them, but in the poems, he says things like “hundreds and thousands of trays of baklava.” He talks about baklava and pastries. “Some with almonds, some with lentils,” he says. The next things we know about baklava are found in the palace accounting books during the reign of Sultan Mehmed II. The books do not say that baklava was made especially for the sultan, but there is no way it could have been for anyone else. By the 16th century, poets writing odes and ghazals mention baklava in their poems. From this we can see that the importance of baklava is much more than the importance given to any other dessert. The spiritual value of this dessert is first seen as related to Ramadan, but in the 16th century, whenever something was celebrated, baklava was always served. Baklava has a symbolic meaning. It is a celebration dessert. It becomes a dessert that represents happiness and goodwill. Among all the beautiful Ottoman desserts, only baklava gains such a place. It is actually interesting.

Everyone thinks that the filling of baklava is mainly pistachio, but it is not. All the baklava makers I spoke to in Gaziantep and Istanbul told me that until the mid-1970s, the predominant production was walnut.

Do you have any explanation about this??

P.M.I.: Baklava is very similar to börek, because it is made with phyllo dough (yufka). Yufka is very old and important in Turkish culinary culture. You can trace the history of dishes made with layers of phyllo pastry back to Central Asia. Mantı, kaymet, börek… These go back to the 13th century and earlier. When you combine it with the Middle Eastern tradition of adding syrup, you get baklava instead of börek. I think that’s where the origin comes from. We already see “baklava börek” written on menus and in poems centuries ago. At 17th-century banquets, they served börek first, followed by baklava.

A dessert like baklava cannot be attributed to a single culture and nation. Food is not like that—it travels. Moreover, everyone in this geography lives side by side in each other’s kitchens.

What is the role of crystal sugar in baklava?

P.M.I.: Crystal sugar is not a new ingredient, but in the past, it was more accessible to the rich. There are writings that talk about white sugar centuries ago. Iran in particular was advanced in sugar refining technology. Even in Afghanistan, you could see white sugar. It depends on the process; you process it a lot and filter it a lot, and it becomes white. So there is sugar, but it was accessible to the rich. Of course, white sugar is always the priority in making baklava, because sugar gives sweetness to baklava, but it doesn’t have its own taste. Honey, on the other hand, has its own unique taste, and that taste can overpower other ingredients. The same with jams—they contain the flavor of the fruit.

B.O.: The 20th century is much more active in terms of transformation of the ingredients. There has always been sugar from sugar cane, but in the 19th century, they managed to extract sugar from beets. This technology, developed at the end of the 18th century, spread rapidly in the 19th century, and by the middle of the century, there were huge beet fields and sugar production from beets increased in factories. As a result, the price of sugar fell rapidly and sugar became widely available and accessible. During the 20th-century world wars, glucose and fructose syrups were developed, and these became widely used in dessert production. It is not acceptable to use these syrups in desserts, but we know that they are used in commercial baklava.

So, how have the techniques of making baklava changed over time?

B.O.: The basic ingredients of baklava are flour, sugar, and oil. If sugar is one of the elements that has evolved, oil is another. Traditionally, baklava is baked in the oven with clarified butter—an expensive and high-quality fat. But especially in times of scarcity, clarified butter became harder to access. Margarine was invented in the late 19th century, again as part of a story shaped by crisis and famine. Over time, the technology behind margarine improved, and by the early 20th century, it became entirely plant-based. Throughout the 20th century, we see a shift from clarified butter to margarine in commercial baklava production. But let me emphasize even today, using margarine is still not considered acceptable by traditional standards.

These are all developments that emerged in the industry starting in the early 20th century. Both margarine and glucose syrup had already entered the market in the late Ottoman period. We understand from early municipal regulations—such as “If you use glucose syrup in your desserts, label it; if you use margarine, specify it”—that some baklava producers began favoring these ingredients to cut costs as early as the Republican period.

However, the choice to use margarine wasn’t always about profit. From the 1950s to the late 1970s, margarine was widely seen as a respectable component of modern cuisine. There was a common belief that “you never know what other fats are or how they’re produced, but margarine comes from a factory—so it’s clean, sterile, and modern.”

What about the other part of the story—the flour?

B.O.: As I said, baklava is essentially a dessert made from sugar, oil, and flour. The filling can vary, but those three are the foundation. Now, regarding flour—during times of famine in the 20th century, using flour in baklava was actually banned. Naturally, this posed a challenge for baklava makers, but it didn’t stop production altogether. For instance, Burhan İnal, one of the oldest living baklava masters, told us in an interview about the flour shortages during World War II: “Flour would be sent to the military and the governor’s office, and they would send some to us to make baklava for official guests. We’d keep a bit of it for ourselves and sell it.”

The biggest changes in the use of flour came in the 21st century. The most significant development has been the rise of gluten-free baklava. At the beginning of our book, we define baklava as “a dessert made with flour, oil, and sugar.” But by the end, you’ll see that the new varieties emerging in the 2010s include versions without clarified butter, without wheat flour, and without sugar. Today, there are baklavas on the market that leave out all three of the ingredients we originally gave as the foundation.

In an 18th-century book, soldiers preparing for a military campaign are given this advice: ‘Once a week, your maid will make baklava and you will eat baklava.‘

Baklava is a dessert claimed by many nations and ethnic groups as their own. Does baklava really have a nationality?

P.M.I.: The groups that lay claim to baklava today—Greeks, Turks, Armenians, and Arabs—all once lived within the Ottoman Empire, and all had their own versions of baklava. Everyone prepared this dessert with slight variations, which is why I think the debate over who owns it is unnecessary.

Baklava is made with phyllo dough, and while rolling it does take some skill, it’s something people across the spectrum—from rural households to city dwellers and palace kitchens—learned to do. In fact, among those who migrated to Istanbul from villages without a tradition of baklava-making, the first two things they learned were how to make dolma and how to make baklava. Take that line from the 18th-century manual: “Once a week, your maid will make baklava and you will eat baklava.” It reflects how baklava was something that could be made in nearly every home, which helped it spread. It became popular simply because it was a delicious dessert—and there were many ways to make it. Some people still make it with honey, though I haven’t tried it myself. In some versions, rosewater was added, but we have very little historical detail on that.

B.O.: And of course, this isn’t a debate unique to baklava. Nation-states came into being much later and needed to define themselves—both geographically and culturally. In that process, food became a tool for drawing lines: who we are versus who we’re not. At its core, the battle over baklava is really a struggle over national identity. But when it comes to baklava, it’s nearly impossible to make a definitive claim. As Mary mentioned, baklava belongs to everyone who made it and ate it. The question of “Who made it first?” is often raised. We know, for instance, that baklava is mentioned in the works of Kaygusuz Abdal. But even if we could somehow transport the baklava he ate to today, I doubt it would resemble the baklava we know now.

Of course, we could still call it baklava—but we’d have to acknowledge that it’s gone through enormous transformations. Cultures borrow, adapt, and evolve. One group might introduce a method, another a new ingredient. You build on what came before and turn it into something new. It’s a dynamic process. If the history of baklava teaches us anything, it’s that we shouldn’t look at food through an essentialist lens. The baklava we hold in our hands today—the first image that pops up when we type “baklava” into a search engine, the glistening slices we see on bakery counters—this “authentic” version only took shape in the 20th century. A dessert like baklava can’t be claimed by a single culture or nation. Food doesn’t work that way. It moves, it blends, and it evolves. Especially in this part of the world, where everyone has long lived side by side—in each other’s kitchens.

What interesting facts about baklava did you come across during your research?

B.O.: One of the most fascinating things is how, since the 2010s, baklava has gone through a kind of revival, driven by market culture and consumer trends. There’s a growing variety now—what looks like innovation is often actually a return to old recipes. For example, baklava made with honey might seem new, but it appears in Ottoman-era recipe books. Even baklava with fruit, like melon, is nothing new.

The reason we think these are modern inventions is because, for much of the 20th century, trade and commercialization standardized baklava. There were usually just two or three types on offer at any given time, so people forgot that other versions even existed.

My research into the 20th century is full of these kinds of misconceptions. For instance, everyone assumes pistachio is the standard filling—but it wasn’t always that way. All the baklava makers I interviewed in Gaziantep and Istanbul said that until the mid-1970s, baklava was mostly made with walnuts. They said about 50% of it was walnut-filled, 30% with clotted cream, and only 20% with pistachios.

Also, contrary to popular belief, Gaziantep isn’t the birthplace of baklava. It became associated with baklava after the rise of the nation-state. Still, there’s a grain of truth here: Gaziantep helped define the dominant technique, especially the ultra-thin phyllo dough. That style eventually became the standard.

It’s a bit like aşure—everyone has a very specific idea of how baklava should be. Over time, the notion of “home baklava” emerged as something more “authentic” and desirable.

P.M.I.: Shop-bought baklava often tastes a little bland to me. Maybe it’s the additives. I’ve spoken to many women across regions, from Erzurum to Bingöl, who make traditional baklava at home. They would say, “We used to roll the phyllo so thin, you could read a newspaper through it.” And they almost always use walnuts in their baklava.

B.O.: That’s partly because unroasted pistachios were hard to come by until recently. Walnuts, on the other hand, could just be picked from trees in the garden. Whether home or shop baklava is considered better really depends on your social circle.

For example, Turgut Kurt recalls in his memoirs: “When I was a child, if someone brought baklava home from a shop, people would criticize the woman of the house—‘Doesn’t she know how to roll out baklava?’” In the 1930s and 40s, shop-bought baklava wasn’t popular. Being able to serve homemade baklava was seen as a sign of care and hospitality. But after the 1970s, buying baklava started to signal appreciation. Shop baklava, especially the expensive kind, became a marker of status. Just carrying that fancy bag from a well-known baklava shop became a prestige move. With the rise of advertising and celebrity baklava makers on TV, homemade baklava began to imitate the versions sold in stores.

Home baklava” is almost always made by women. I remember when I was little, my mother and the neighborhood women would gather before holidays to make baklava together. One would roll the dough, another would cut it. They’d fill tray after tray this way.

B.O.: That reminds me—while writing the conclusion of my chapter, I realized I had told an almost entirely male story. In the commercial sphere, everything is dominated by men: the dough rollers, the syrup makers, the shop owners. Women are missing from the picture. There’s this common claim that “you need strength to roll the dough thinly, and women can’t do that.” But everything you and Mary shared shows the opposite. At home, women do roll the dough, and they do it well. Yet in the professional world, the moment it becomes a “job,” suddenly it’s framed as something women aren’t suited for.

P.M.I.: I came across a source that said in the 16th century, during Ramadan, vast amounts of baklava were made in the palace to be distributed to people, including soldiers. The phyllo was prepared by women in the city and then brought to the palace. This may have been a more regular practice than we realize—but unfortunately, the records are scarce.

What kind of research process does the historiography of a specific food or dessert require?

P.M.I.: It really depends on how skilled you are at finding diverse sources. For example, to go beyond cookbooks and figure out who was actually making baklava, I combed through probate records looking for baklava trays. If someone had a baklava tray in their house, it usually meant they made baklava. So I asked: who were these people? Were they wealthy or not? You can tell by looking at their other belongings in the same records. Unsurprisingly, wealthy individuals—like lady sultans—had lots of baklava trays. But even in the early 16th century, and even as far back as the late 15th century, you find a few baklava trays among non-elite households too. These were often modest but not impoverished people—like the wife of an imam—who had baklava made at home. That’s why probate records are so valuable when studying everyday life. I also drew from poetry. There’s one poem, a full ghazal, dedicated entirely to baklava! In others, poets complain, “I’m starving, I can’t even get a bite of baklava.” Or you see lines from guards lamenting, “Ah, if only there were baklava at work, I could eat some.”

These texts show that baklava was a known, longed-for treat. Maybe not everyone could afford it often—or at all—but it existed vividly in the public imagination. The longing in those verses says a lot. Some go as far as: “If only I could eat baklava… I can’t live without it.”

B.O.: The kind of sources you use really depends on the theme you’re working with. Writing a history of baklava in the 20th century was quite different from my earlier research—because I did oral history for the first time. As a historian, I used to find it comforting not to deal with living people. So, stepping out of that comfort zone was a challenge at first, but in the end, those oral testimonies were both enjoyable and illuminating. Like with any source, though, you have to be critical—people’s memories shift, and what they recall can change over time. Still, oral history gave me access to voices and experiences that traditional sources wouldn’t have shown. Ultimately, the story of baklava isn’t just about food. It’s tied into broader political, social, and economic histories. Each source opens a different window into that larger picture.

Levon Bağış: “The History of Civilization Emerges from the Journey of the Grape”