Levon Bağış: “The History of Civilization Emerges from the Journey of the Grape”

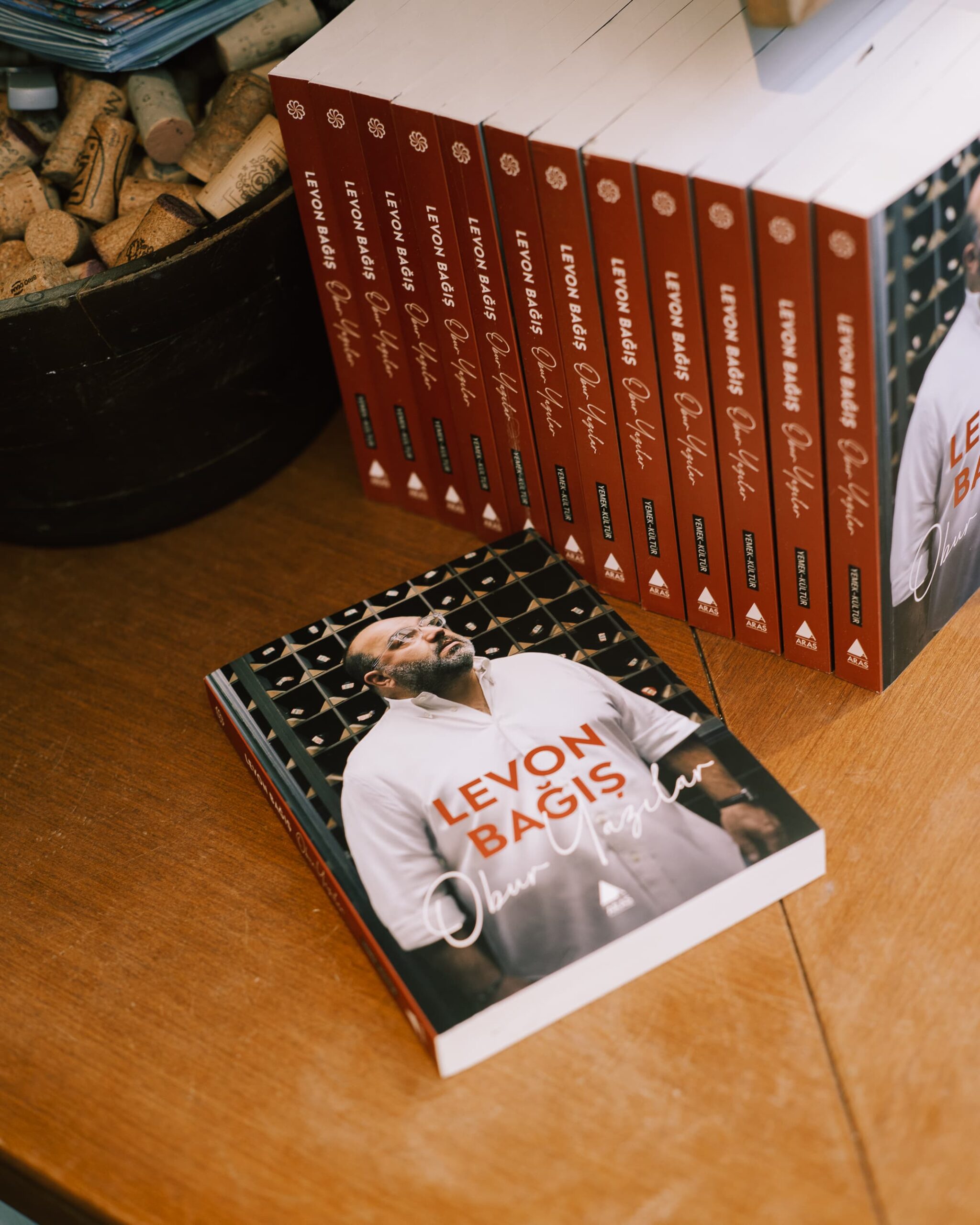

We had a deep conversation with Levon Bağış, whose book Obur Yazılar (Gluttonous Writings) has just hit the shelves, about the journey of the grape and viticulture in Turkey. Naturally, we also made Istanbul’s ears ring.

Doğu and Suray (D&S): After our previous interview with you, we remembered you saying, “I thought you would ask more questions about fatherhood.” When we saw in the introduction to your new book Obur Yazılar that “In 2017, their son Ararat was born, whom they would later name a wine they would produce,” we had to ask—how is life with Ararat?

Levon Bağış (LB): If I were to describe life with Ararat in one word, it would be “fun.” Before becoming a father, you imagine raising and educating your child, thinking, “This is how my child will be.” Then you realize, with some horror, that he is actually arriving with his own character, thoughts, desires, and truths. In the end, it’s the opposite of what you expected. While you think you will educate him, before you know it, that tiny being is educating you. If I had to sum up my relationship with Ararat, I’d say, “He is training me.” Fatherhood changes your entire perspective—your understanding, your perception, and the decisions you make. In simple terms, it turns a father into a man. And in that sense, it’s incredibly rewarding.

D&S: You also mentioned on We Talk Food Even at Dinner (Yemekte Bile Yemek Konuşuyoruz) with Sinan and Nilay that you were keen on ensuring Ararat experienced aspects of your own childhood and built certain memories—perhaps as a way of passing on the culture of being an Istanbulite?

Levon Bağış: I was born in 1980, and I think of my generation as an in-between one. As children, we played ball in the streets, rode bicycles, scraped our knees, climbed trees, and stole fruit. But we also had an Atari, and later, computers entered our homes. We witnessed the arrival of technology rather than being born into it, which makes a difference. The new generation, however, is immersed in technology from birth—a reality that is both fortunate and unfortunate.

I believe they should also experience aspects of the past. A child born in Istanbul should be able to recognize the fish at a market stall, know the names of the winds, and distinguish whether it’s lodos or poyraz blowing. To truly belong to a city, you need to understand its codes. That’s what I want for Ararat.

This is why spending summers on the island is important to me. There, children can still play in the streets, learn to ride a bike, and then set off with friends to explore. They can still buy ice cream from a street vendor. And most importantly, they can swim in the sea. In a city like Istanbul, I believe everyone should have one foot in the water.

D&S: When we read the introduction to At a Long Table, we thought: You have always had a political stance and have never hesitated to reflect it. How did this stance take shape and develop?

Levon Bağış: I believe that everything is class-based and rooted in economic foundations, and I see class struggle as something very valuable. I am not in favor of sharing poverty—I am in favor of sharing wealth. In other words, we will create wealth, and we will share that wealth, God willing.

The reason for my political stance is probably where I grew up, and especially my father. If you asked me to describe him in one word, I would say only one thing: he is a man of justice. The main quality I seek in my family and friends is a sense of justice. And by justice, I don’t just mean the justice of an individual or a specific group—I dream of a world where people truly live fairly. This may be a utopia, but we must believe in utopias. We cannot live without embracing them. My favorite saying is: “Be realistic, ask for the impossible,” as Che Guevara said. We will ask for the impossible, but that does not diminish our right to be realistic. A sense of justice and fair sharing are important. It matters that we consume wealth and the pleasures of life together, that we sit and talk.

So when I set that long table, the most important thing for me is that everyone sitting there is equal. It doesn’t matter who they are—everyone eats the same food, shares the same conversation. The magic of that table is equality. Even if a child or a young person is there, they have a voice. They have a plate, and they share that plate with you. That’s why I find long tables so precious.

Since we’re on the subject, I want to highlight something else. I think the rise of “fine dining” in the 1980s disrupted our food and drink culture and rituals. Maybe this is connected to the times—Reagan in the U.S., Thatcher in the U.K., and Özal in Turkey. It was an era that promoted individualism, where “I” became central, and the idea of “I deserve the best” took root. Of course, fine dining is a beautiful thing—I enjoy it—but in the past, at our long tables, food was never the main star. It was about the people—the friends, the family, the conversation. Food was there, but it was never the leading role.

Now, when you go to a fine dining dinner for two, whether it’s twelve or fifteen plates, it doesn’t matter—a lot of food arrives. Every ten minutes, someone comes to explain a dish. You inevitably talk about the food and the wine. But maybe you never even talk about yourself, your life, or your friendship with the person you’ve been sitting with for hours.

The table I imagine is never a fine dining table. You know that scene in The Godfather where the whole family sits under the vine, eating together? If you ask me what my ideal table is, what the only table I dream of looks like—that’s the one.

D&S: Speaking of which, let’s continue with the book Obur Yazılar (Gluttonous Writings). It is a selection of articles published in your gastronomy column Obur (Glutton) in Agos. How did this process unfold? How did you feel revisiting these articles?

Levon Bağış: I hate reading, watching, or listening to myself. I just can’t do it—every time I read an article, I find a mistake; every time I listen to an interview, I notice something missing. I don’t enjoy it. That’s why I never reread my own writings, not even for corrections. My editors have always been quite unlucky in that sense. When Gluttonous Writings was published in Agos, Altuğ, who edited my articles, put in tremendous effort. It took a long time for those articles to eventually become a book.

I don’t consider myself a bad reader. I follow new releases, buy a lot of books, and have a nice library. I enjoy owning books and spending money on them. But I’ve come to realize something—newspaper and magazine articles are tied to the moment in which they are written. They belong to that specific day and context. I never found much interest in seeing them republished later. I thought they had served their purpose at the time they were written.

The late Brother Tomo, the owner of Aras Publishing, was an extraordinary person—one of the most influential figures in my life, though he probably never realized it. He played a key role in shaping my intellectual identity. He believed these articles were valuable and should be compiled into a book. I didn’t feel I had the right to disagree with him. In the end, he insisted, and that’s how this project began. One day, the book’s editor, Rober—who had also introduced me to writing at Agos—called and said, “I spoke with Tomo Abi. I’m taking over the book this year. I’m sorting your articles and preparing them for publication. Just so you know, your book will be out soon.” And that’s exactly what happened. In short, I had almost no involvement in selecting, proofreading, or editing the articles.

D&S: In your articles, you don’t just discuss food and drink culture—you also present a philosophy of life. Some pieces are autobiographical and, at times, quite emotional. How do you capture this depth? Does it come naturally, or do you follow certain writing templates?

Levon Bağış: I don’t believe I follow specific templates, but I probably do. I don’t intentionally structure my writing in a particular way or think, “This is how it should be done.” But about a week or ten days after the book came out, I realized something interesting—I had been influenced by two writers without being consciously aware of it.

After Selim İleri, a writer I deeply admired, passed away, I picked up Oburcuk Mutfakta (Oburcuk in the Kitchen), a collection of his food and table-related memories, to flip through again. As I did, I realized how much his writing had influenced me. I wrote in a similar way to him.

Then, my dear friend Bilge Bey—a winemaker and the owner of 7 Bilgeler Winery—called me recently to chat about my book and said, “Your writing gives me a Salah Birsel vibe.” That might be one of the most beautiful compliments I’ve ever received. I love Salah Birsel’s work, and his book Boğaziçi Şıngır Mıngır is one of my favorites. So perhaps I was influenced by him as well.

I truly believe in a saying I heard from Tan Morgül: “Those who only understand football don’t really understand football.” A football man said this, and I really like it. The same applies to food and wine—those who understand only one or the other truly understand neither. Because neither food nor wine, nor any other drink, exists as a commodity in isolation. They are part of a whole, shaped by their stories and origins.

Take lakerda, for example. If you talk about it purely in a hedonistic way, focusing only on its taste, it means one thing. But if you view lakerda as part of this land’s heritage, passed down for thousands of years, it takes on a completely different meaning. The same goes for wine and raki. You could recount five hundred years of Ottoman history—of Istanbul’s history—through raki alone. Just raki. You could trace the geography of Ottoman travel and influence solely through raki. You could even tell a history of civilization through the journey of grapes. This is what fascinates me and what I find worth telling.

I write a lot about wine, but I don’t write tasting notes. My tasting notes are usually just for myself—to remind me what a wine meant to me. I believe tasting is a personal experience, and that experience should be judged on its own terms. That’s why I rarely publish tasting notes. For me, there are wines worth writing about and wines that aren’t. If I write about a wine, it’s because it is worth it to me. I view my entire writing journey through this lens—some things are worth writing about, and some aren’t. And ultimately, whatever is worth writing about compels you to write.

Vintage 2024: A Hot, Dry, and Early Harvest

D&S: Another thing that caught our attention is your habit of beginning your writings with quatrains or quotes. That’s how you started the introduction to our book. Who do you particularly like to reference, and what kind of sources inspire you when you write?

Levon Bağış: I think I’ll start my answer with a reference again. Murat Uyurkulak has a book called Delibo, and there’s a line in it that deeply affected me: “The greatest curse of man is that he has no talent for what he is enthusiastic about.” It’s truly a burden. One of my biggest ambitions in life was to write poetry. Actually, let me put it this way—I wanted to write poetry, take good photographs, and play an instrument. But I can’t do any of the three. So, in a way, I am living that curse twice over.

Since I can’t write poetry, I read good poetry. Since I can’t take good photographs, I collect photography books. Since I can’t play an instrument, I have a carefully curated record collection. I try to compensate for my shortcomings by living like a hunter-gatherer. My use of quotations comes from the same impulse. I have a good memory—when I start writing about a subject, sometimes a spark goes off in my mind, reminding me that someone, somewhere, has written something relevant. And I track it down.

We live in a fortunate geography. The rise of raki culture in the 1950s and 60s coincided with the emergence of the Second New poetry movement. As a result, the golden age of raki and the era of the poets I love most overlap. Thanks to the Second New movement, raki has a rich literary presence. On top of that, we come from a tradition with a wine poet like Ömer Khayyam. If I’m writing about wine and the word “jug” comes up, I immediately think of his poem about a jug. That’s why I use these references—because they come to mind naturally. It’s a mix of reading, writing, and, to some extent, emulation. Because sometimes, I honestly admire how a poet captures in a single stanza what I struggle to express in a page and a half.

D&S: Do you have any new book projects in mind? Or perhaps you’re not yet certain about your next book…

Levon Bağış: Actually, there is something in the works. While Rober was compiling my articles, he also archived many that hadn’t been published in Agos. These pieces had appeared in various magazines, here and there. For now, he chose not to include them in the selection, thinking we might use them later. If I continue writing elsewhere and the body of work grows, perhaps such a book could be published. I also have a wine book project that has been dragging on for about five years.

D&S: You mean our long-awaited, utopian wine book?

Levon Bağış: Yes, exactly. Our utopian wine book. That dream is still alive. Hopefully, it will happen one day.

D&S: Let’s talk a little about the training sessions you conduct. How do you approach wine education? What kind of requests do you receive?

Levon Bağış: I do it in my own way—mainly because I don’t know any other way. My sessions aren’t rigid, textbook-based, or meticulously structured. But I do have one advantage: I’ve been giving wine training almost since the day I started learning about wine. It’s been a long time, and by now, the training process has become somewhat second nature.

But here’s the thing. I believe that if someone explains something—whether it’s wine or any other subject—in a pompous, overly abstract, or half-intelligible manner, they probably don’t fully understand it themselves. So, when I talk about wine, I aim for clarity. I don’t know how successful I am, but I want even someone who has never thought about wine to grasp what I’m explaining. To achieve that, I simplify the concepts and use relatable examples. When discussing malic acid, I compare it to a green apple. To explain whether tannins and bitterness work well together, I bring up why people might drink tea with the infertile (stale) bread they bake at home. I try to connect with people through familiar experiences. Because otherwise, elaborate but vague storytelling might look impressive from a distance, but in my view, it only reveals the speaker’s lack of true understanding.

D&S: How important is it for you to train experts in the wine world? What’s the best approach? Do certificates matter, or is hands-on experience more valuable? Or should it be a combination of both?

Levon Bağış: Ideally, it should be a mix of both. Can someone learn about wine purely through hands-on experience, like an apprentice? Absolutely. But formal training can accelerate and systematize the learning process, making it highly valuable. However, we shouldn’t forget this: simply having a certificate doesn’t make someone a wine expert—at least not when it comes to wine.

There’s only one real way to deepen your knowledge of wine. Whether you have a degree, have studied at a university, have trained in oenology, or have taken basic or advanced courses, the true measure of understanding wine comes down to this: Can you analyze what you’re drinking? Can you determine whether it’s good? Can you articulate it to others? And to do that, you need to taste a wide variety of wines—constantly.

The biggest challenge for me and my colleagues in Turkey is being stuck in a monotonous wine landscape. We have different regions and excellent terroirs, but when we attend a blind tasting of Cabernet Sauvignon, we often encounter wines made with the same yeast and enzymes, aged in the same barrels, produced in the same style—what I call “machine carpet” wines. They’re technically flawless, well-crafted, but uniform. Wines should move away from this mechanical sameness. They need more dimension—perhaps made with native yeasts, sourced from distinct terroirs, using the right clonal selections. The winemaker should leave an artistic imprint on the wine. Our biggest challenge is that wines with true character are hard to find. They do exist, of course, but they’re rare.

About twenty years ago, when I first went to London to study wine, I attended a wine tasting where “elderflower” was mentioned as one of the aromas in the wine. Until that day, I had never even heard the word “elderflower.” While its direct Turkish translation is “mürver çiçeği,” it actually refers to the elderberry flower. After the course, my winemaker friend and I went to a florist and asked for “elderflower.” I’ll never forget it—the guy laughed at us. He said it wasn’t a flower but a berry and that we could find elderflower-flavored sodas in the market. Then he added that if we wanted to experience the aroma, we could try wines made from the “Macabeo” grape. We were stunned—a florist knew about a grape we didn’t even recognize.

That experience made us realize how, after every training session, we had the chance to visit a wine shop around the corner, buy dozens of different wines, and taste them. We don’t have that opportunity here. I know firsthand the challenges faced by my friend Ayça, the director of IWSA, one of Turkey’s leading institutions for WSET training. They struggle immensely to find foreign wines for proper training. It’s incredibly difficult to access these wines for education, and it’s frustrating that people here lack the resources to develop their expertise.

D&S: When we last interviewed you, neither “Foxy” nor “Yaban Kolektif” existed. You’ve done truly transformative and influential work in our wine world. Let’s start with Foxy, where we’re meeting for this interview. This is a wine bar with a menu exclusively featuring wines made from local grapes. How do guests react to this? Are they disappointed when they don’t see a “Cabernet Sauvignon,” “Shiraz,” or “Sauvignon Blanc”?

Levon Bağış: When my partner Maksut Aşkar and I were envisioning this place, we were determined to create this kind of wine menu—and we did. We braced ourselves, expecting resistance from customers. We thought people would react negatively to a wine list without international grape varieties, and we were prepared to stand our ground. But in the end, all that preparation was unnecessary. The reactions weren’t what we expected at all.

When we tell customers we don’t serve wines made from foreign grapes, their response is usually, “Okay, what do you recommend, then?” Of course, this is part of Foxy’s appeal. Everyone here is passionate about wine and well-educated in it. They exude confidence, which makes guests trust their recommendations—and they’re usually satisfied.

Operationally, we don’t face any major challenges. The only real drawback compared to a typical restaurant is that we can’t generate the same profit margins. High-end wines made from international grapes sell at premium prices, but local producers rarely create luxury-tier products—except for one or two. That’s the only aspect of Foxy that wears me out.

I should also mention that we have a significant foreign customer base. And by the way, I don’t say “guests” because we charge people money. I recently heard İnanç Çelengil say this on Ayça’s “Tasting Conversations” program, and it really resonated with me. It’s true… Anyway, foreign customers come here curious about endemic grapes from this region. They expect to try something local. As for our local customers, we have nearly two hundred wines on the menu—they always find something that suits their palate.

D&S: Let’s move on to the Wild Collective. Everyone we’ve shared the story of Yaban with—whether at tastings or in our shop—has fallen in love with it. We, too, admire this pioneering work. How has the Yaban project resonated with winegrowers, other producers, and consumers?

Levon Bağış: In the early years of the project, when we went to Çorum to buy Sungurlu White or to Van for Erciş Karası, we encountered winegrowers who were reluctant to sell us their grapes for various reasons. Today, those same winegrowers—along with others who initially refused—now call us as harvest season approaches, letting us know they’re preparing grapes for us.

Maybe the fate of the region hasn’t changed drastically, but at least for Sungurlu White, I can say this: in the beginning, we sourced grapes from just one or two vineyards. Now, more and more people—including the intermediary who connected us with the village—have started tending to their idle vineyards and growing grapes again.

It might seem like a small thing, but to me, it’s significant. Today, one of Turkey’s top producers is making wine from Sungurlu White. Another has planted this grape in his own vineyards. Yet another has started producing wine from Erciş Karası. These are meaningful steps. They show that efforts to keep these grape varieties alive are paying off—at least to some extent.

Of course, this doesn’t mean that just because we’ve intervened, these grapes are guaranteed to survive. But as in the story of the starfish, something is changing for the ones we’ve thrown back into the sea.

D&S: We have our own ideas, but we’d like to hear from you first. Where is our wine world heading? Especially in light of developments over the past decade—considering both consumer preferences and the production side—can you share your thoughts?

Levon Bağış: We have a major problem, and it’s not just about wine. Producing anything in Turkey is a challenge—cheese, olive oil, you name it. Our whole story revolves around dealing with agriculture and farming in a country where production is so difficult, and then trying to make wine on top of that. When it comes to wine, there are additional burdens. Winemakers are under serious threat due to laws that are in flux—some passed, some rejected, some canceled. Given this instability, it becomes incredibly difficult for any producer to invest in vineyards, expand their existing investments, or try something new and experimental.

When the top priority for all winemakers in Turkey, from the largest to the smallest, is simply survival—at the very base of Maslow’s hierarchy—progress is impossible. Producers need to feel secure and stable before they can focus on improvement and innovation. That’s why the work of all winemakers in Turkey, no matter their size or reputation, is admirable in these circumstances.

But admiration doesn’t mean we should overlook their mistakes. Today, Turkish wine producers—and even the broader wine market—need to take a hard look at themselves. In my view, we are moving toward an unsustainable market. This isn’t solely the responsibility of producers, because the wine industry is an ecosystem. Within this system, there are producers, distributors, retailers, restaurateurs, and consumers.

Wine prices in Turkey today are unrealistic. Producers may have valid reasons—some costs are genuinely high. But we also see producers pricing their wines based on a flawed logic: “If his wine costs this much, mine should be more.” Meanwhile, large supermarket chains operate with excessive profit margins. This situation is not sustainable.

When I first entered the wine business twenty years ago, pricing was already a major issue. Back then, drinking raki at a tavern was a more economical choice. Later, wine gained ground. But now, a decent bottle of wine costs nearly as much as high-alcohol spirits. This darkens the future of wine in Turkey. Another issue is that Turkey’s so-called expensive wines aren’t truly expensive.

D&S: We understand what you’re saying, but can you elaborate on your statement: “Turkey’s expensive wines are not expensive”?

Levon Bağış: Some wines are sold at around twenty euros in the market. These are quality, special wines, and globally, that price point is standard. You can buy a wine of similar quality for the same price in California. Except for a few exceptionally low-cost markets, this is the norm.

The real issue is that the wines in Turkey’s “expensive” category are actually the ones that should be affordable for daily drinking—the bottles you should be able to put on your table every evening without hesitation. These are the ones that are overpriced.

D&S: Let’s leave the drinking side and move on to dining. The Michelin Guide has suddenly arrived. Restaurants are getting “Gault&Millau” reviews. Chefs are gaining prominence. Gastronomy is rapidly evolving, and everyone is striving to run a “cool” restaurant. Meanwhile, income distribution in the country is what it is. Dining out has become a luxury for most people. We seem to have a complex gastronomic world where everything is intertwined. Will this complexity stabilize?

Levon Bağış: I think it’s valuable that institutions like Michelin and Gault&Millau are recognizing Turkey. But there’s also a risk. These institutions, all over the world, tend to put pressure on local, authentic restaurants. There’s a perception that everyone must become the kind of restaurant Michelin and Gault&Millau will favor.

This is similar to what happened with wine in the 1990s—the so-called “Parkerization” effect, where wines started to conform to certain styles to win high scores. The same could happen here. Instead of making traditional dishes like baked beans and rice, some chefs or restaurateurs might think, “Why bother? I’ll just go fine dining, put white tablecloths down, and chase awards.” That mindset is a risk. Of course, these guides do try to respect local culinary values, but that’s not always how they’re perceived.

That said, recognition is motivating. People are happy to see their work appreciated. Of course, we can debate the rankings—does this place deserve a star? Should it have one or two? But all rating systems are subjective. We’ve all been surprised at wine tastings when a wine we don’t particularly like gets a high score. The same applies here.

Now, to the other part of your question. On one hand, high-end restaurants are multiplying; on the other, people’s purchasing power is declining, making dining out difficult. The fact that this has become a topic of discussion is itself troubling. Going out for a meal should be normal. If we’re talking about not being able to eat out even once a week, that signals a much deeper problem.

So what happens when fewer people dine out? Restaurants must find ways to survive. This often means cutting costs—narrowing menus, using cheaper ingredients, hiring fewer staff. Ultimately, this leads to mediocrity. When you enter that cycle, it’s a slippery slope: “Let’s use lower-quality olive oil, let’s operate with two waiters instead of five, let’s skip the busboy.” Mediocrity doesn’t stay static—it spirals downward.

If we have aspirations for gastronomy in this country, restaurants need to be accessible. But from a restaurateur’s perspective, running a respectable restaurant under these conditions is incredibly unprofitable—far more than most people realize.

D&S: In our previous interview, we talked about your cool glasses. This time, let’s talk about watches. Do you wear a watch regularly? Any special ones?

Levon Bağış: I wear a watch regularly and love them, but the watches I dream of but can’t afford far outnumber the ones I own. I’m something of a watch enthusiast. I’m fascinated by unique mechanisms—watches that chime on the hour, those that track moon phases.

But my most cherished watch is my Seiko 5, which I inherited from my father. I deeply appreciate it. One watch brand I admire is Rolex, though in recent years, some consider it a sign of ostentation. Personally, I respect Rolex for its design and ethos. I also like that it operates as a foundation, distributing its profits within a structured framework. (We both laughed and said, “Kolektif!” upon hearing this.) Rolex also sponsors our Heritage Vines of Turkey project, which adds another layer of appreciation for me.

D&S: You often end your articles with a greeting. Would you like to close our interview with one?

Levon Bağış: Do I really do that so often? Then let me answer by tying it to watches. For me, an object’s value isn’t just monetary. I have a watch from my grandfather—one of my most treasured possessions. Or take the watch I’m wearing now—at first glance, it may look like a child’s watch, but it’s a limited-edition piece featuring Corto Maltese, one of my favorite comic characters. I prefer it over many so-called “cool” watches.

Owning a watch—or even just understanding and appreciating one—is about more than the object itself. The same goes for fountain pens. In an era where people hardly use notebooks and pens, cherishing a fountain pen is an act of refinement. I call these “the subtleties of life.”

So, if I’m sending a greeting, let it be to everyone who appreciates these subtleties. Because, just like wine, a watch doesn’t have to be expensive to be meaningful. In fact, some of the most expensive wines can be disappointing, while a modest one can bring immense joy. It’s the story, the heritage, and the experience that truly matter.