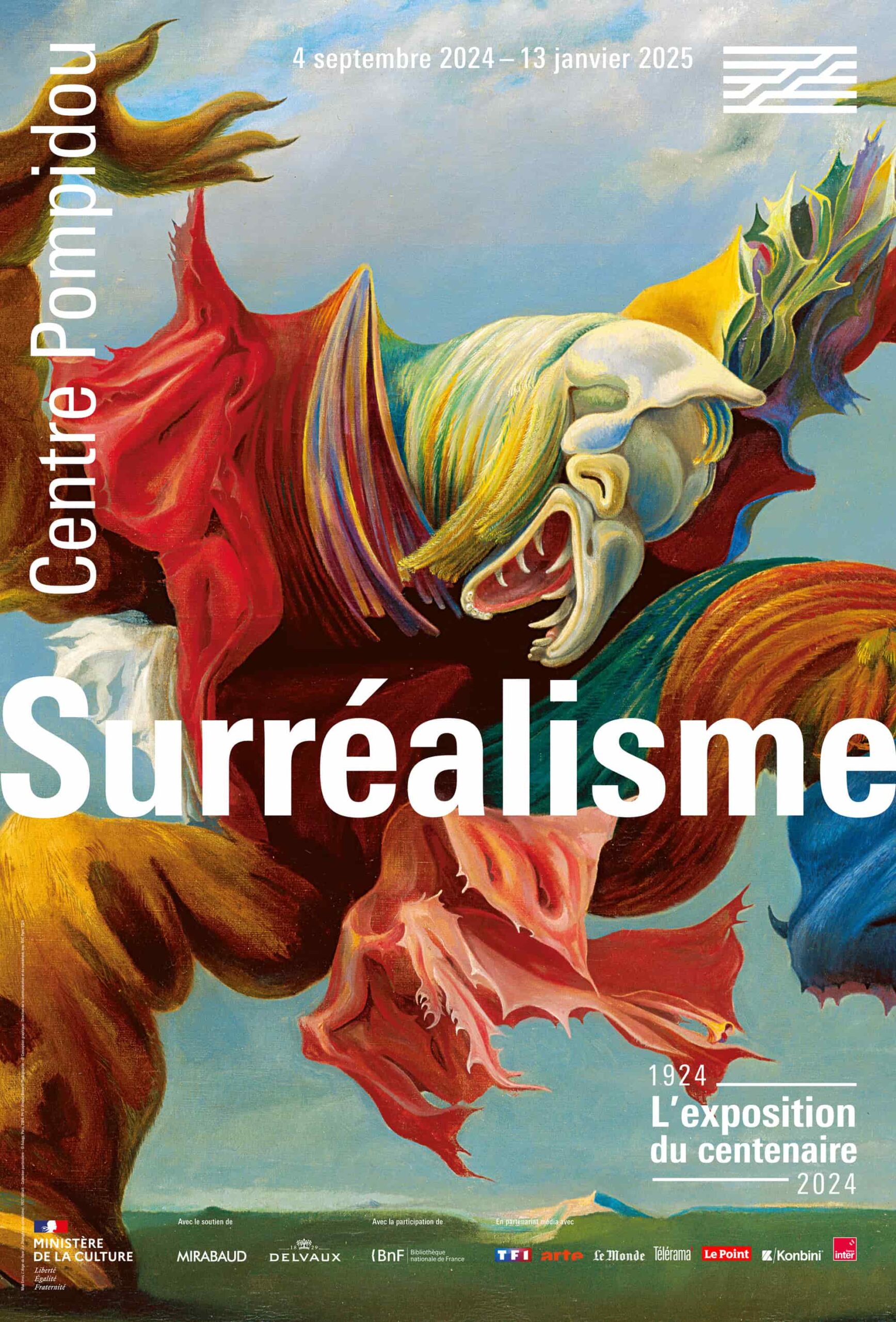

Celebrating the 100th Anniversary of Surrealism

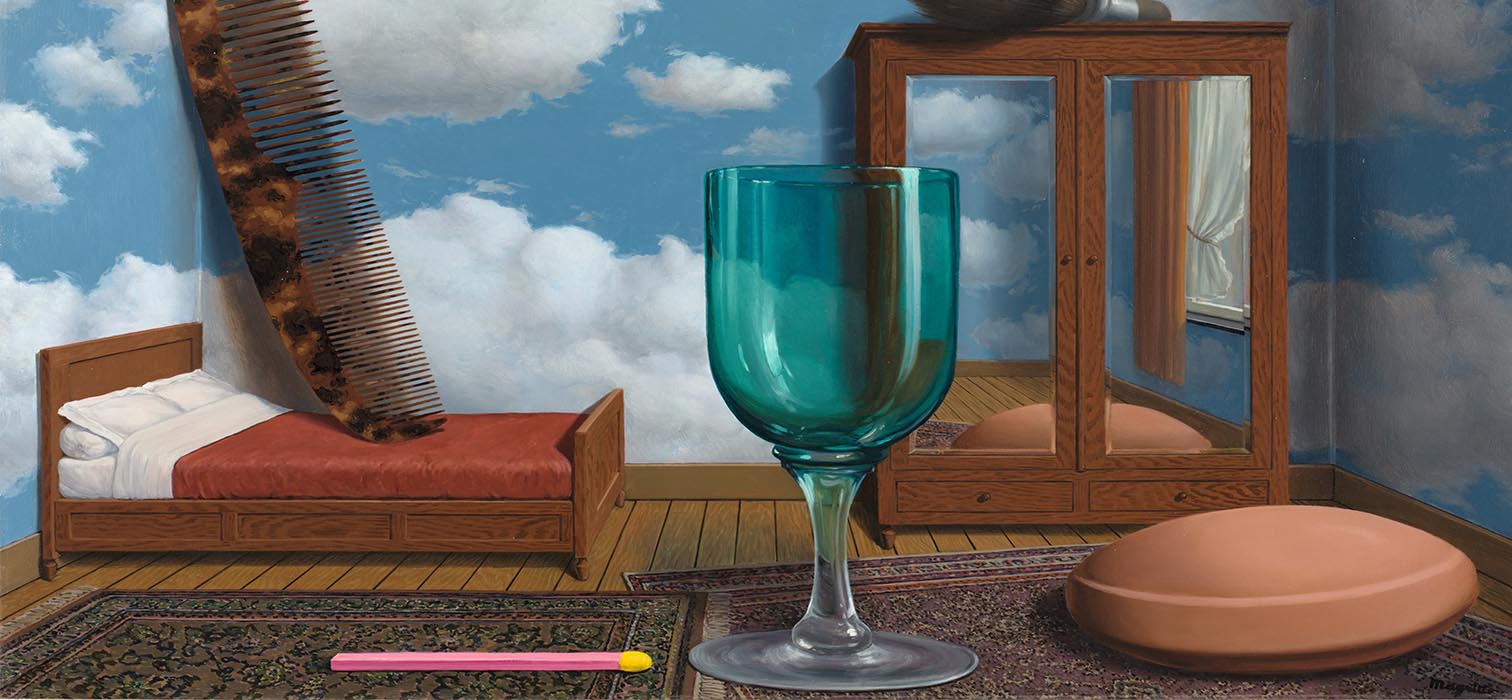

The creativity of a period of more than 40 years is revived in the exhibition prepared for the 100th anniversary of Surrealism.

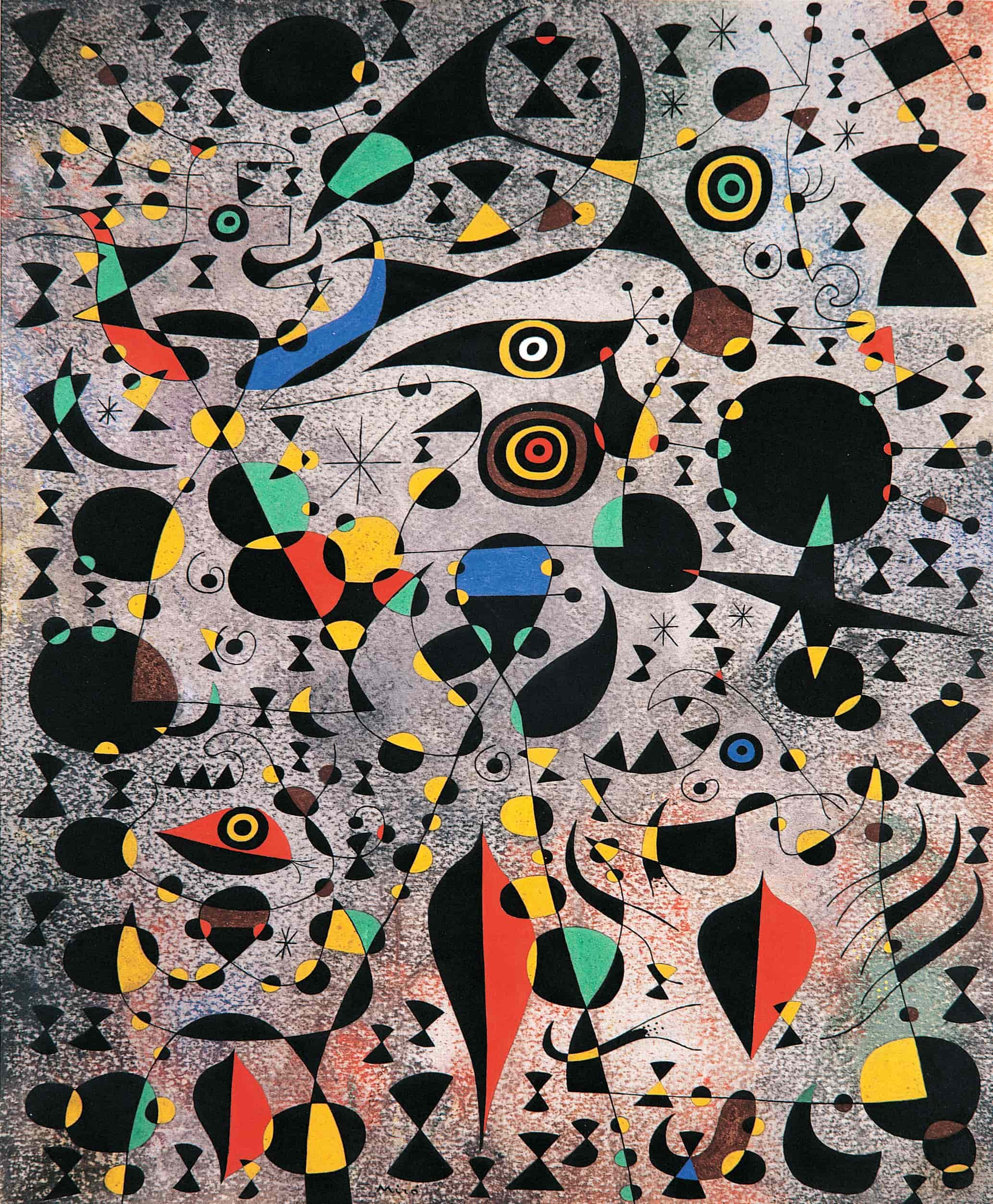

Marking the centenary of André Breton’s Manifesto of Surrealism, the Centre Pompidou’s “Surrealism” exhibition revitalizes over four decades of the movement’s creative force. This dynamic retrospective unites paintings, drawings, films, photographs, and literary works, capturing the imaginative spirit that fueled Surrealism’s impact on art and culture.

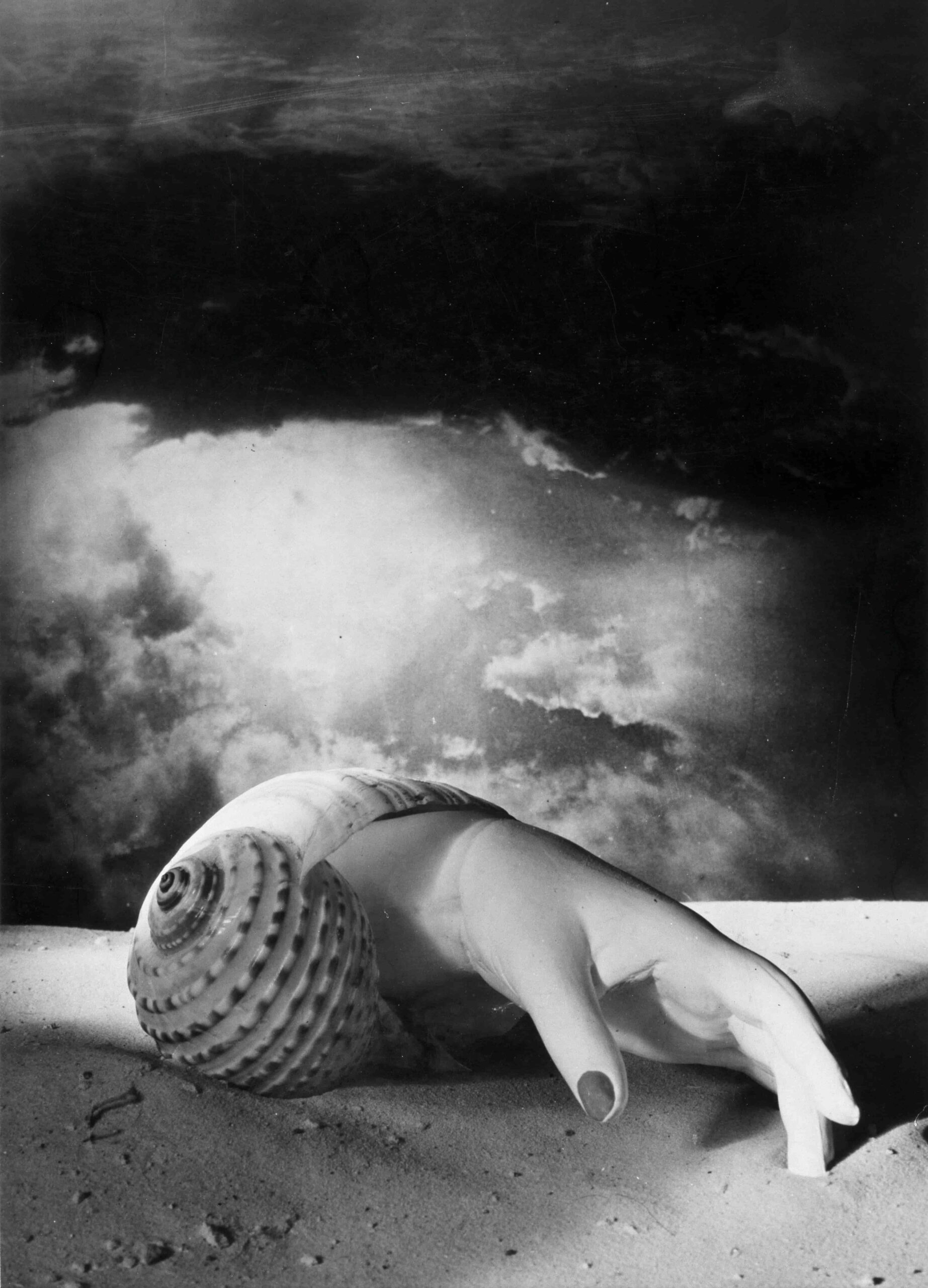

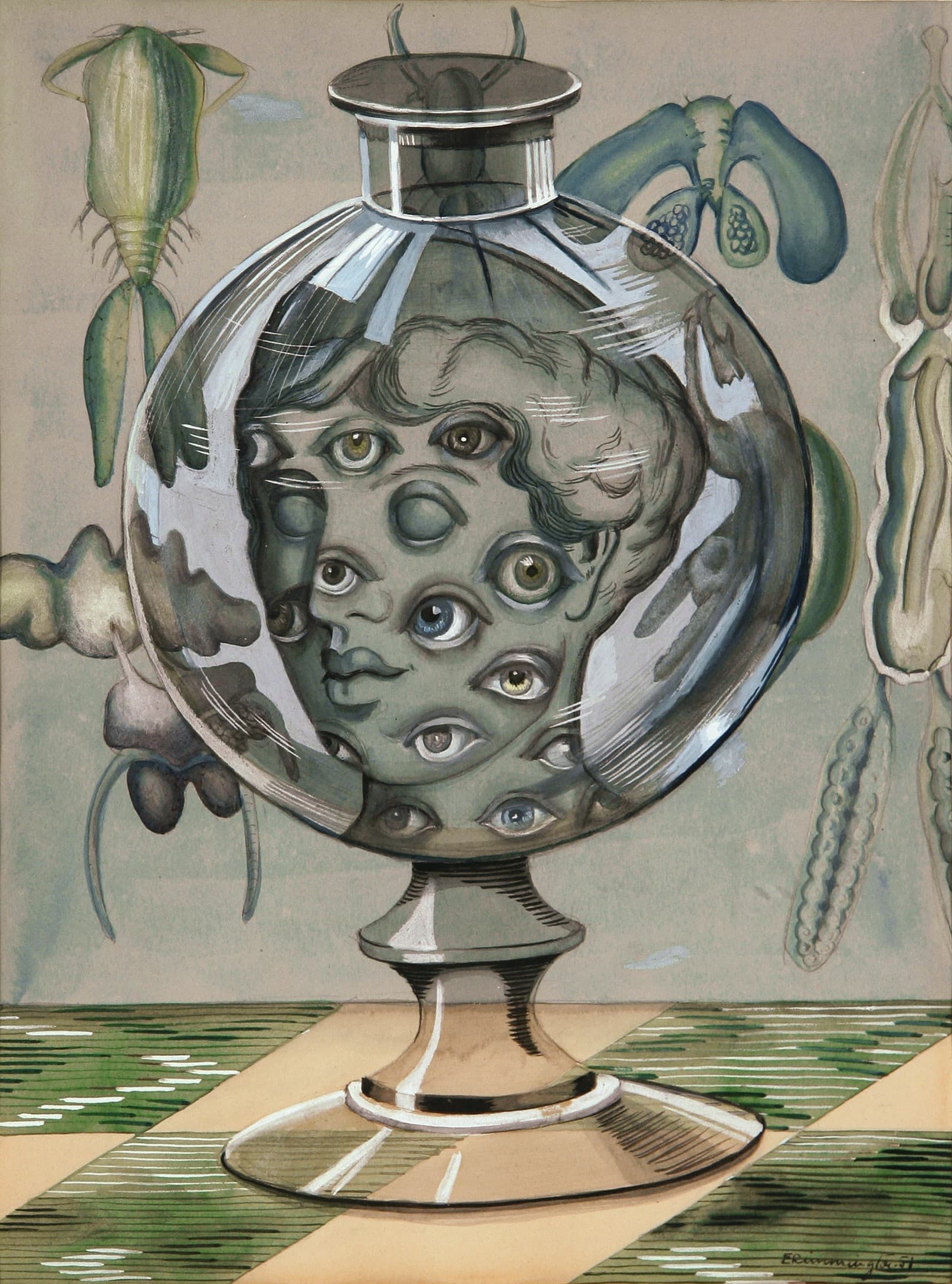

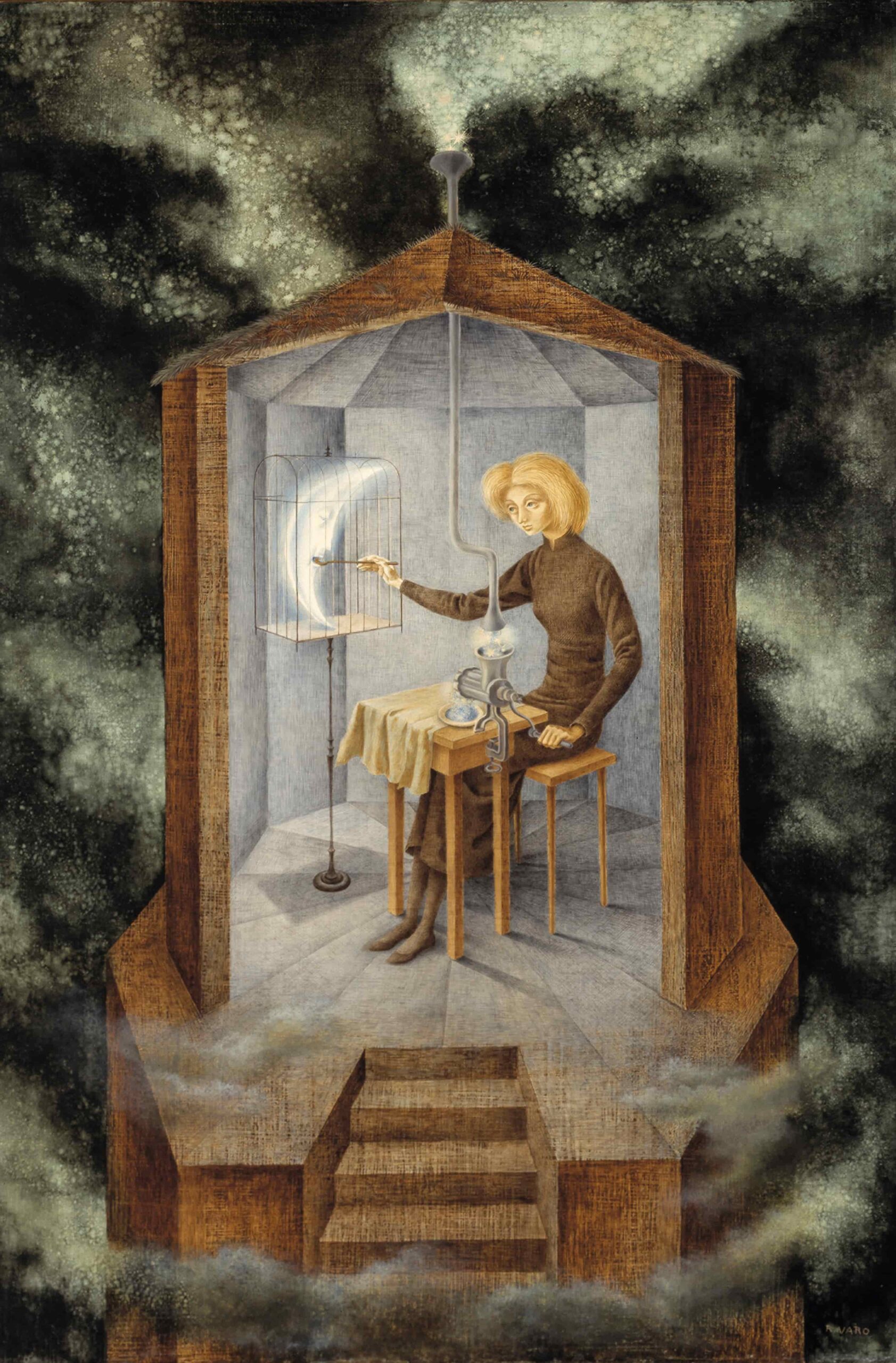

In keeping with the Centre Pompidou’s tradition of multidisciplinary showcases, “Surrealism” shines a spotlight on the often-overlooked contributions of female artists like Leonora Carrington, Remedios Varo, Ithell Colquhoun, Dora Maar, and Dorothea Tanning. The Surrealists’ resistance to a civilization driven by technological rationality, alongside their fascination with diverse cultures such as Antonin Artaud’s study of the Tarahumara people and André Breton’s exploration of Hopi traditions, reveals their modern sensitivity toward cultural diversity.

While Surrealism as a movement formally ended in 1969, its influence remains ever-present, inspiring contemporary art, fashion, film, and even comic books.

- Design Miami.Paris 2024: Where History Meets Contemporary Design

- A True Hat Maestro: Stephen Jones

- Pieter M. van Hattem: The Hunter of Magical Moments

- From Plato’s Cave to the Basilica Cistern: Yeraltının Kapıları

Curators’ Insights

Marie Sarré, curator of the exhibition, reflects on the exhibition’s goals two decades after Centre Pompidou’s iconic La Révolution surréaliste: “Surrealism has long been viewed as an avant-garde movement that concluded by 1940, but it endured through the post-war period until its dissolution in 1969. Highlighting Surrealism’s legacy after WWII, the exhibition challenges the idea that Surrealism was exclusively European, emphasizing its reach across the USA, Latin America, North Africa, and Asia. Women’s roles have also gained new recognition—not only as muses but as essential artists within the movement. Surrealism drew mass audiences to its exhibitions, and in this spirit, the Surrealism exhibition is curated with a thematic approach that seeks to map the poetic imagery central to the movement.”

When asked about Surrealism’s lasting relevance in 2024, curator Didier Ottinger captures the movement’s enduring impact: “Surrealism has always achieved a delicate balance, blending Rimbaud’s call to ‘Change life’ with Marx’s imperative to ‘Change the world.’ From the outset, Surrealists were politically active, fighting colonialism, opposing totalitarianism, and championing freedom and human dignity. Even years later, the movement spread globally—from Prague to Tokyo, London to Cairo—like a constellation of liberation. It also welcomed more female artists than any other art movement of its time. The Surrealists’ critique of civilization, a challenge to the obsession with technology and consumerism, is a legacy that endures. Like Romanticism before it, Surrealism has kept a critical eye on society.”

One of the exhibition’s highlights is a tribute to the 1947 surrealist show designed by Marcel Duchamp as a labyrinth—a symbolic space that reconciles life and death, the real and the imaginary, the past and the future. This maze embodies the Surrealists’ embrace of opposites, capturing the spirit of the movement from its inception to its end. Visitors are invited to surrender to the surreal experience, leaving preconceptions at the door and entering a world guided by the movement’s dreamlike logic.

Organized into 13 sections that unfold both chronologically and thematically, the exhibition explores Surrealism’s literary roots and the myths that enriched its imagination.

Exploring Surrealism’s Fascination with Psychics

Surrealism celebrated poets as “clairvoyants,” individuals attuned to the universe’s deeper mysteries and capable of reconnecting poetry with ancient prophecy. This mystical sensibility appeared as early as 1914, when Giorgio de Chirico painted Guillaume Apollinaire with a bullseye on his forehead—a haunting premonition of the head wound Apollinaire would suffer three years later. André Breton furthered this notion in Entrée des médiums (1922), where he documented hypnotic sleep sessions among future Surrealists.

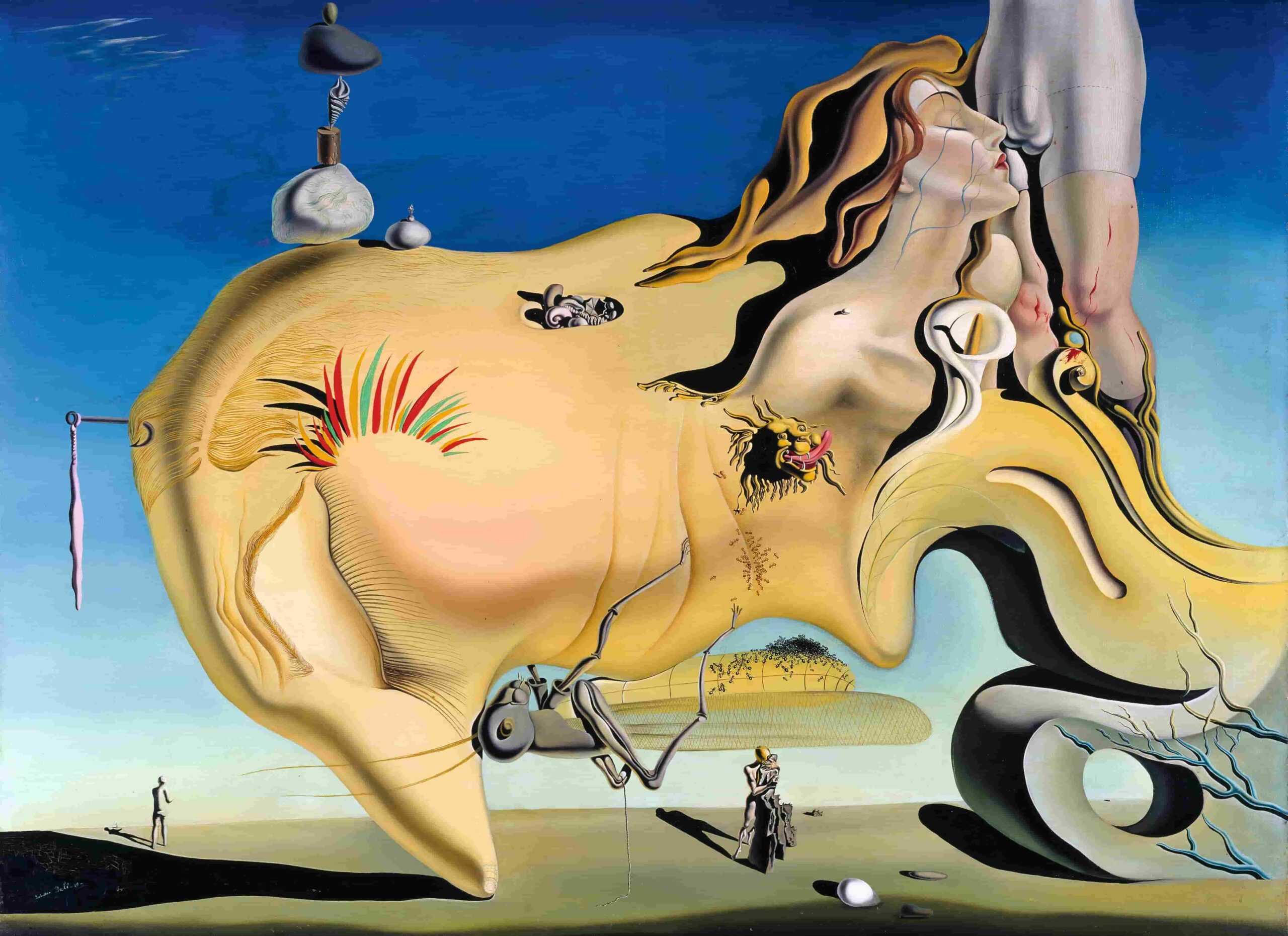

These explorations of the unconscious profoundly influenced their art, mirroring the creativity seen in individuals with psychotic disorders. Techniques like automatic writing, as seen in Breton and Philippe Soupault’s Les Champs magnétiques (1919), Max Ernst’s frottage, and André Masson’s sand paintings, brought their dreams and visions to life.

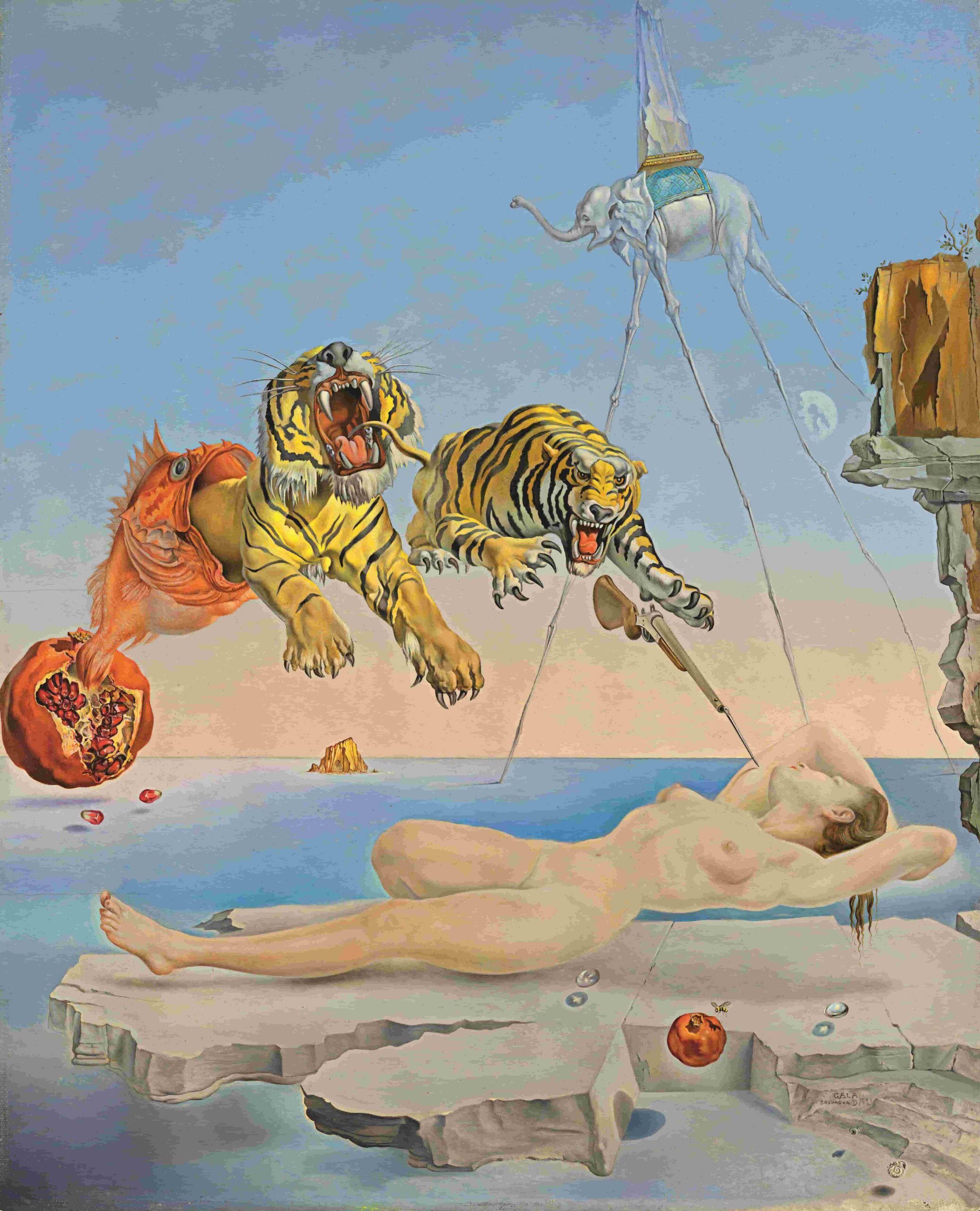

The Journey into Dreams

André Breton’s background in medicine and interest in Albert Maury’s Sleep and Dreams (1861) influenced Surrealism’s embrace of the dream world. His work at a neuropsychiatric center in 1916 introduced him to Freud’s pioneering methods of treating psychotic patients by interpreting their dreams. The Surrealists began using psychoanalytic insights in their poetry and art, publishing dreams in journals and pursuing the enigmatic images that linger on the edge of sleep.

In 1932, Breton and Paul Éluard combined dream and waking reality in Communicating Vessels. Here, Breton speculated on dreams as keys to life’s essential questions, a theme central to the Surrealist Manifesto. This ongoing engagement with dreams reflected Surrealism’s quest to transcend ordinary perception and unlock the mind’s hidden potential.

Lautréamont

In 1914, the magazine Vers et Prose reignited interest in Isidore Ducasse, known as Comte de Lautréamont, whose work had faded into obscurity after his early death at just 21. Philippe Soupault’s life was transformed upon reading Lautréamont, prompting him to share this discovery with André Breton.

Breton, in turn, introduced Lautréamont to Louis Aragon, establishing a new literary myth for the burgeoning Surrealist movement. Lautréamont’s Les Chants de Maldoror, with its tumultuous and violent narrative, resonated deeply in a world scarred by war. His infamous definition of beauty—“the chance encounter of a sewing machine and an umbrella on a dissecting table”—became foundational to Surrealism’s collage aesthetic.

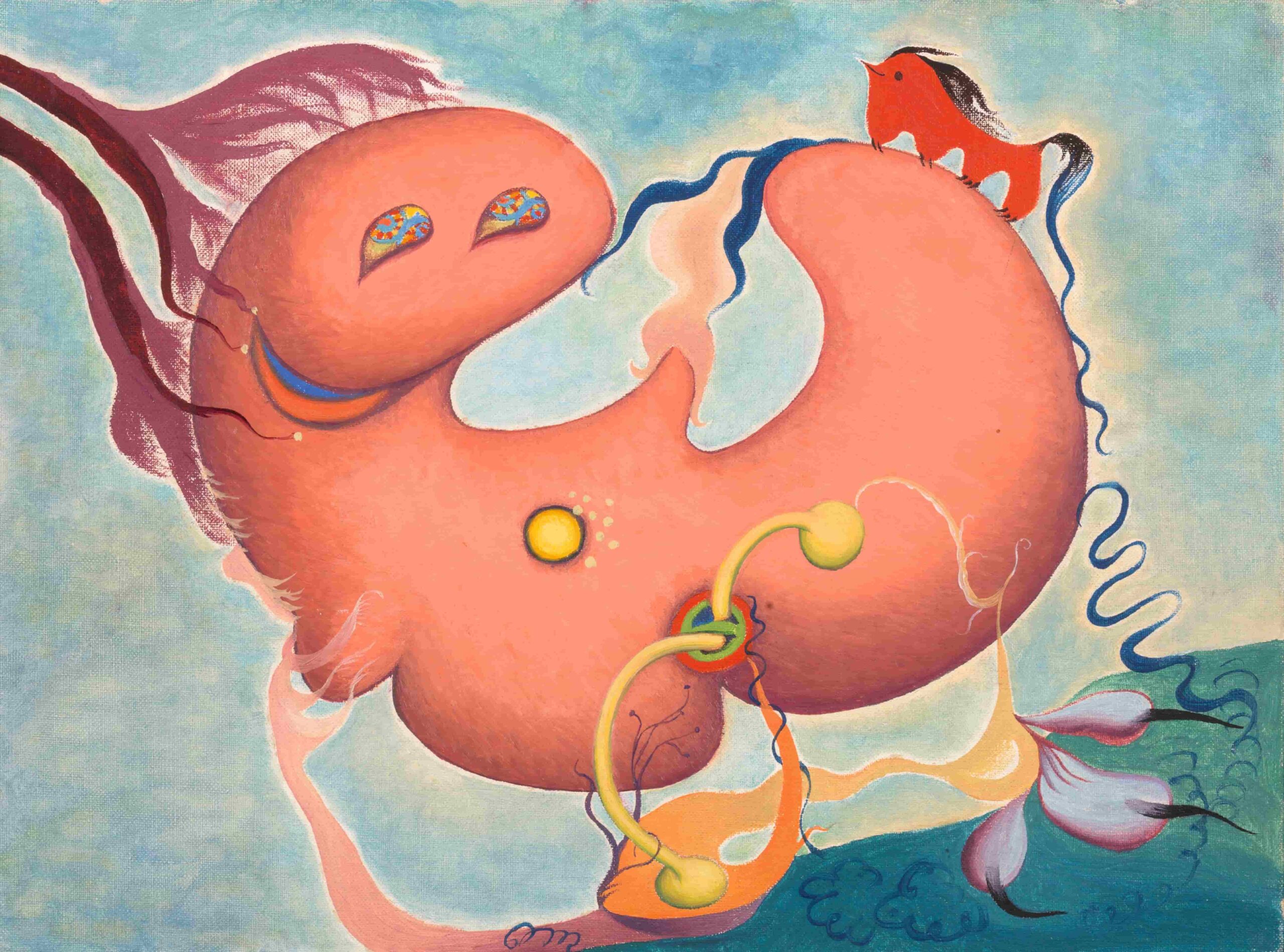

Chimera

The mythical Chimera, a creature depicted by Homer in the Iliad as a bizarre amalgamation of a lion, snake, and goat, fascinated the Surrealists with its illogical form. In 1925, they conceptualized the game Exquisite Corpse, inspired by Lautréamont’s assertion that “Poetry should be done by everyone, not by one person.” Initially conceived as a word game, the technique soon evolved into a collaborative drawing exercise. The resultant creations were fantastical beings that no single imagination could conjure, solidifying the Chimera as a potent symbol of a world steeped in anarchy and the unpredictable possibilities of collective creativity.

“Childhood is perhaps the closest thing to real life.”

Alice

André Breton once remarked, “Childhood is perhaps the closest thing to real life,” reflecting the Surrealists’ profound admiration for Alice in Wonderland, a work that encapsulated the boundless imagination of youth. In 1931, Louis Aragon penned an essay on Lewis Carroll, solidifying Alice as a central figure within the Surrealist canon. Aragon also translated Carroll’s The Hunting of the Snark, further intertwining Alice’s whimsical world with Surrealist ideals. The logic-defying realm Alice inhabits led Breton to herald Carroll as a pioneer of Surrealism in his Anthology of Black Humor, positioning Alice as a symbol of rebellion and the unrestrained freedom inherent in childhood.

Political Monsters

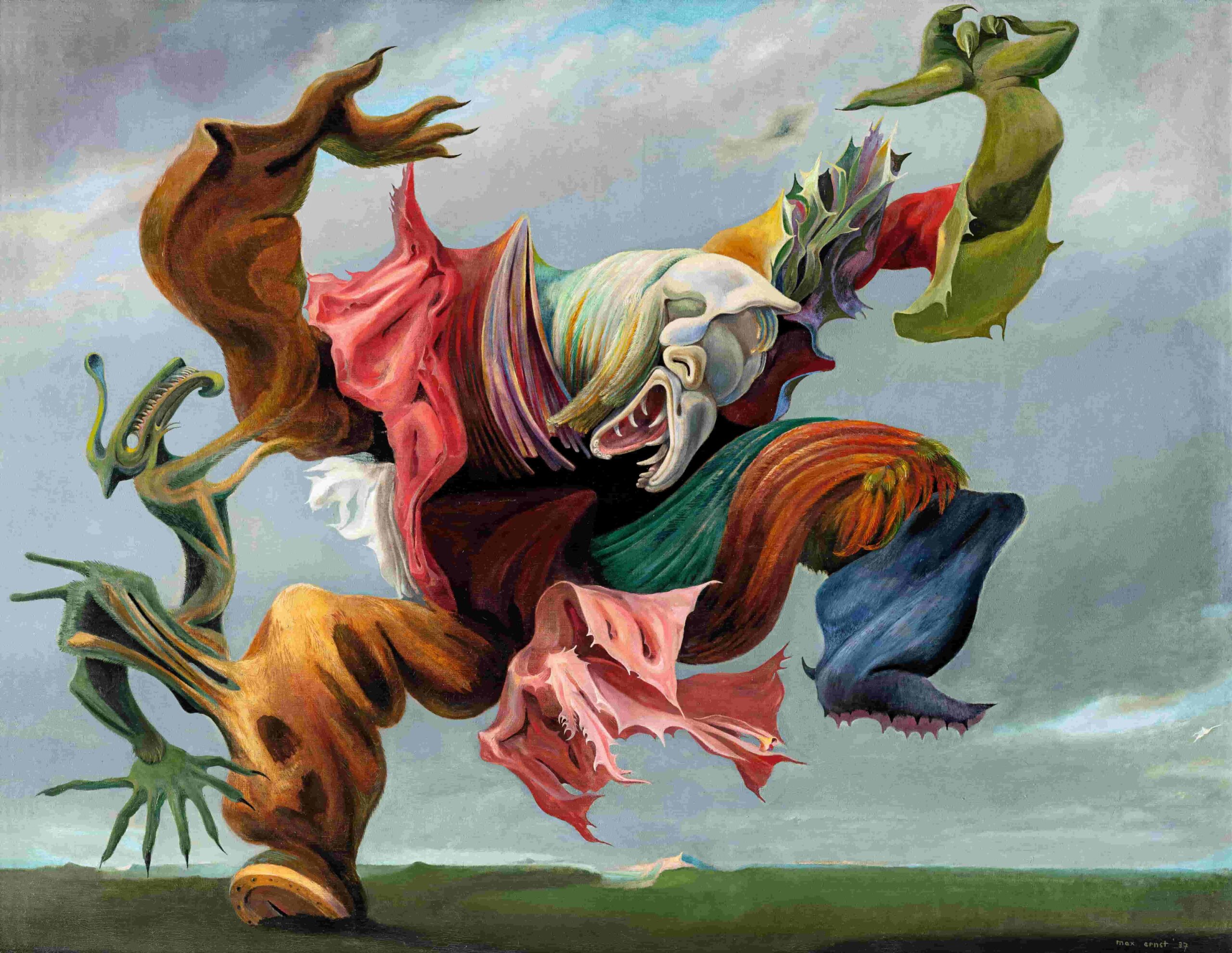

Surrealism emerged from a synthesis of two pivotal ideas: Karl Marx’s imperative to “change the world” and Arthur Rimbaud’s aspiration to “change life.” In 1925, the Surrealists engaged with politics, collaborating with the young communists of the Clarté group to draft a manifesto denouncing France’s colonial war in Morocco. As fascism loomed in the 1930s, many artists began to scrutinize the nexus between their artistic endeavors and political responsibilities. During this tumultuous period, Surrealism birthed “monsters” that symbolized the encroaching threat of totalitarianism. In 1932, shortly before Adolf Hitler’s rise to power, a new Surrealist magazine adopted the mythological Minotaur as its emblem, embodying the chaos and danger of the times.

Kingdom of Mothers

The “Mothers” referenced by Goethe in Faust II evolved into a significant poetic myth within Surrealism. In 1927, André Breton introduced Yves Tanguy at his inaugural art exhibition, declaring him the first to uncover the “Kingdom of the Mothers.” These maternal figures were perceived as dynamic creative forces, capable of instigating profound change in an instant. For the Surrealists, mothers epitomized constant transformation, nurturing the creative processes exemplified by automatic writing. Artists such as Grace Pailthorpe, Jane Graverol, and Salvador Dalí also recognized “Mothers” as an inexhaustible wellspring of imagination.

Mélusine

The legend of Mélusine, a being half woman and half snake, has its roots in medieval fairy tales. André Breton revisited this myth in Arcane 17, composed during his exile in America. In this work, he delved into themes of harmony with nature, drawing connections to the expansive landscapes of New Mexico and eastern Canada. Mélusine emerged as a symbol of reconnection with nature’s fundamental elements. Breton’s interactions with Native American cultures further shaped his vision of a future where humanity was intimately tied to the natural world.

Forests

For poet Charles Baudelaire, the forest represented a mystical realm where hidden relationships could be unveiled. The Surrealists adopted the forest as a potent symbol of subconscious exploration and metamorphosis. Artists like Max Ernst, influenced by the darkness and mystery inherent in German Romanticism, integrated forest imagery into their works. Meanwhile, Cuban artist Wifredo Lam critiqued the devastation wrought by colonialism, portraying the forest as a celebration of untainted, primitive nature. In a 1938 essay, Benjamin Péret interpreted the sight of an abandoned train traversing the forest as a testament to nature’s triumph over human progress.

Philosopher’s Stone

In his Second Manifesto of Surrealism, penned in 1929, André Breton underscored the parallels between Surrealism and alchemy. Alchemy served as a metaphor for the Surrealists’ ambition to fuse knowledge with poetry, as well as the art of transmuting base metals into gold. Historical alchemists such as Hermès Trismégiste and Nicolas Flamel became vital sources of inspiration for Surrealist artists. Within this context, alchemy was regarded as a “science of love,” illustrating the interconnectedness of all aspects of existence. Breton’s epitaph, “I seek the gold of time,” encapsulated his belief in alchemy’s profound and transformative potential.

Hymns for the Night

In Hymns to the Night, published during the Romantic period, Novalis celebrated the “ineffable, sacred and mysterious night.” The Symbolist poets, influenced by this theme, embraced ambiguity, with Victor Hugo noting, “He who thinks lives in darkness; he who does not think lives in blindness. We can only choose black.” Gérard de Nerval heralded the emergence of the Surrealist night in Aurélia: Dream and Life, a juxtaposition of opposites that inspired André Breton’s paradoxical title Sunflower Night and René Magritte’s Empire of Light series. In Paris By Night, Romanian photographer Brassai captured the transformative power of metamorphosis, turning a modern city into a mysterious, archaic labyrinth. Following the legacy of nocturnal figures like Nosferatu and Fantômas, the Surrealists enveloped visitors in darkness and uncertainty during the Exposition internationale du Surréalisme exhibition at the Galerie des Beaux-Arts in Paris in 1938.

“Perhaps man is not the center or the focal point of the universe.“

Tears of Eros

André Breton, declaring that “the most distinctive feature of Surrealist works is primarily their erotic connotations,” positioned eroticism at the forefront of Surrealism and redefined “L’Amour fou” (mad love) in its purest form: a passion so intense that it could provoke mental disorders. Surrealist love emerged as both a scandalous and revolutionary force. The Marquis de Sade was a pioneer in the pursuit of absolute freedom, with his influence palpable in the works of Alberto Giacometti’s Unpleasant Object, Hans Bellmer’s Doll series, and the provocative poetry of Joyce Mansour. JJ Pauvert, the publisher of Sade’s writings, endured a three-year court battle over these controversial texts. Nonetheless, eroticism was chosen as the primary theme at the 8th Exposition internationale du Surréalisme (EROS) held at the Daniel Cordier Gallery in 1959, solidifying its centrality in Surrealist art.

Cosmos

In his 1942 Introduction to the Third Manifesto of Surrealism or Not, André Breton contemplated humanity’s role in the cosmos, pondering, “Perhaps man is not the center or the focal point of the universe.” This idea positioned Surrealism as a counterpoint to the modern world’s detachment from nature and its urge to dominate it. Instead, Surrealism embraced the medieval notion of continuity between the microcosm and the macrocosm. Breton’s journeys to Hopi lands and Antonin Artaud’s explorations among the Tarahumara Indians underscored the potential for a profound connection with nature. Reinforcing this belief, André Masson’s 1943 engraving The Unity of the Cosmos articulated the universal connection with the assertion, “Nothing in the world is lifeless; there is a relationship between minerals, plants, stars, and animal bodies.”