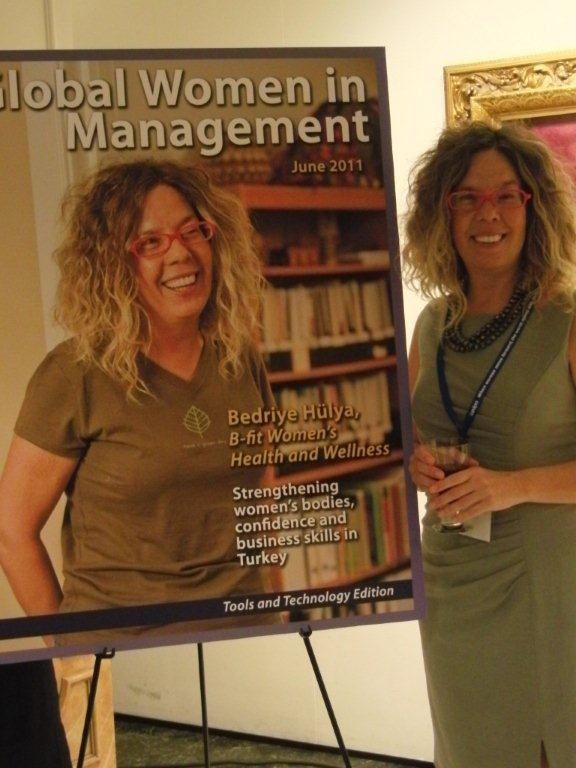

Bedriye Hülya: “Women’s Presence in the Workplace Is My Life’s Work”

We spoke with entrepreneur and psychologist Bedriye Hülya, who, in her new book, shares—with honesty and humor—the realities of being a female entrepreneur. Our conversation turned to gender roles and the working world.

An entrepreneur who never abandons a project once she begins—what she calls her “completion obsession”—Bedriye Hülya is best known as the founder of B-fit, a women-only gym concept. After her ventures reached a certain level of maturity, she handed them over and finally sat down to finish a book she had been envisioning for years. Published by Destek Yayınları, the book offers an entertaining yet incisive account of navigating a male-dominated business world. Titled Kızım Sen Saftirik Halinle Bu İşleri Nasıl Yapıyorsun? Bir Kadın Girişimcinin Seyrüseferi (My Dear, How Do You Manage to Do All This in Your Naive Way? The Journey of a Female Entrepreneur), it is a work that makes readers laugh out loud while allowing every woman—entrepreneur or not—to find a part of herself within its pages. Behind its humor lie Bedriye Hanım’s sharp observations of professional life. After completing the final stage of her psychology training in the U.S. and returning to Turkey, she dedicated her knowledge and experience to helping women feel more empowered in their working lives. We spoke to her about how work shapes gender roles.

How did your working life begin and evolve?

I started working during my first year at university. Then, in 1987, I got married and moved to Bodrum with my then-husband. For a few months, I couldn’t find work, and that period became known in the family as “the time when Bedriye Hanım dismantled and cleaned all the bolts.” I was literally taking apart the stove and scrubbing the bolts one by one. I simply didn’t know what to do with myself. Around that same time, I started getting headaches every morning at ten—they were psychosomatic, of course.

Eventually, I found a job at a bank, though it wasn’t a good fit for me at all. People warned me, “You can’t handle banking,” but I said, “I don’t have a job, so I’ll work,” and I went ahead anyway. I spent six months there, constantly announcing, “I’m going to resign.” After that, I moved to a travel agency. At first, I accompanied tours, but gradually I advanced and became the general manager.

Because business slowed down in the winter, I began setting up my own ventures. I started small, and before long, I realized I had three businesses: a hotel, a restaurant, and the tourism company where I was still working. My mother noticed how exhausted I was and gave me an ultimatum. That’s when I decided to sell. The hotel was doing well, so I said, “I’ll keep this and let the others go.” I had already systematized everything at the tourism company and was becoming bored, so I resigned. The restaurant was also thriving, so it sold immediately. With the extra time, I wanted to study again, so I went to the U.S. to pursue a master’s degree in psychology. We also started a business there, which allowed me to stay.

But once I arrived, I realized I wasn’t as “rich” as I’d assumed. Life in America was financially tough at first. Still, I didn’t complain; I enjoyed every aspect of being there. After launching the business, life became easier, and I studied comfortably. But for six years, I worked nonstop. When the academic year ended, I would fly to Turkey in June and work at the hotel throughout June, July, and August. At the end of August, I returned to school in the U.S.—and, of course, to my job there. I worked for six straight years without a single day off.

During that time, I discovered a gym that used different types of exercise equipment and loved the concept. That was the seed of B-fit. By then, I was tired of running the hotel, too. I told the partners, “Buy me out,” but they didn’t. For a few years, I ran the hotel and B-fit simultaneously, and B-fit grew significantly. Eventually, I said, “Whether you buy my share or not, I’m leaving.” They replied, “If you’re leaving, we’re leaving too,” and we quickly sold the hotel.

So, you believe in building businesses, bringing them to a certain level, and then selling them…

I truly believe that a company must change hands at some point. After a certain stage, keeping the same management becomes a disservice to the business. There’s a limit to what a single leadership style can achieve. Beyond that, someone else needs to come in and take it further. You know how some restaurants or shops proudly say, “No other branches”? I’m not like that. After a while, a business doesn’t belong to me anymore—it belongs to whoever uses it. I have this urge for “someone else to take over.” Although, in truth, that’s also an excuse—I simply want to do new things after a point. I have many interests. For example, I began gradually selling my shares in B-fit in recent years, but the process didn’t move as quickly as I had hoped. I reached a point where I felt certain I no longer wanted to do this job because psychology had become central in my life.

How did you pursue your psychology education?

I completed my psychology training at Columbia University and earned my master’s degree at Hunter College. Between 2014 and 2022, I completed a doctorate in clinical psychology at Arel University. I continue to teach courses such as Organizational Psychology, Feminist Therapy, and Personality Theory—in both English and Turkish—while also conducting individual and group therapy sessions.

How has teaching been for you?

I’ve taught at both private and public universities, and I enjoyed public universities more. Students come from all over Turkey; they’re not privileged children. They are hardworking young people who read, think, and continue to push themselves. I loved that aspect. But now, external teaching is no longer allowed at public universities, so we can’t do that anymore.

One thing I’ve noticed overall is that students’ attention is scattered. Mobile phones play a part, but it’s also the nature of our times. Anxiety levels are extremely high. Yet I also have students with whom classes are a joy—young people who read, observe, ask questions. They give you the strength to keep going. At the same time, there are students who aren’t even aware of their own anxiety and remain distracted.

I love teaching; if I didn’t, I couldn’t do it. I learn a lot from students. I’m naturally curious, genuinely interested in many things. When they say something, I pick up on it and learn. Understanding how their minds work fascinates me. I try to make the class engaging for myself as well. Participation is key for me. For example, no one fails my class because of attendance—I find that absurd. But if they don’t participate, I don’t enjoy the course either. So I work hard to make it a participatory environment.

There seems to be a certain hierarchy in public perception between academia and entrepreneurship. What do you think about this?

One is not superior to the other. I completed my doctorate later in life. In entrepreneurship, you must take risks and put your hand in the fire—it requires courage. Comparing the two is unfair. You can be entrepreneurial as an academic, and academic as an entrepreneur. For example, when we founded B-fit, we conducted numerous surveys and research studies. How many companies do that? We worked with focus groups and carried out in-depth interviews. In that sense, we built the business like academics. Likewise, I approach academia like an entrepreneur. In some ways, I see my students as customers: it’s my job to win them over, to get them to come to class, to motivate participation. That’s simply how my mind works. If your brain operates that way, you approach everything—cooking, playing games, teaching, or starting a business—with the same mindset.

So, how did the idea for the book come about?

I first began writing this book around 2006–2007. B-fit had just launched, I was living in Istanbul, and there was a café I absolutely loved. My apartment was nearby, and I admired the people who worked there. But at that time, I couldn’t even bring myself to go to a café—not because I lacked money, but because I was drowning in work. I was working nonstop. One Sunday I finally said to myself, “Enough—go sit in that café!” So I grabbed my laptop and went.

Back then, I was experiencing things in my company that felt almost surreal. I thought, “Let me start writing these down.” I also wanted an excuse to sit in that café longer. So I began writing, pretending I was some sort of author hiding behind a laptop. It felt a bit silly, but I kept at it for a while. I let a few people read what I’d written, and they laughed a lot. That encouraged me, and I continued writing from time to time.

But I decided I wouldn’t publish the book until I had sold my companies. I’m an outspoken person—I speak my mind very freely. In this country, that can bother people, because we’re not used to such bluntness. Many people are afraid. I didn’t want that honesty to harm the companies. So when I eventually sold my last business, I made a firm promise to myself to finish the book and publish it.

I’m a little “ridiculous” in that way—once I make a promise, I feel compelled to keep it, even if it no longer matters practically. So after selling the last company, I said, “Right, now I’m finishing this.” I immediately found an editor, completed the manuscript, and sent it off. That’s how this journey finally began.

Looking back, how did you manage to achieve all this—how are you succeeding?

The truth is, I don’t actually know what it is I’m “succeeding” at. What people call success, I experience as a compulsion to finish things. Whether I’m organizing drawers or building a company, it’s the same impulse. When I attempt something, my only goal is to complete it, to bring it to a proper end.

I love the feeling of success—but for me, success is completion. Nothing more. Delivering a product, offering a service, creating a finished whole, even simply producing a tidy drawer… that’s the essence of success for me.

You prioritise working with women. What differences have you observed between working with women and men?

I noticed something fascinating at B-fit: when women decide to quit a job, they begin sabotaging it. They want the job to go badly so that they can justify leaving. Men, meanwhile, quit because things are going badly. Women sabotage a job that is going well so that they can leave it.

Many women struggle to simply say, “I’m bored, this job no longer suits me—I’ll sell it to someone else.” Yet that is the rational thing to do. Anyone can become bored with their work. Women come to us saying, “I’ve decided to quit.” You’d think they spent weeks thinking it through, making charts, weighing pros and cons. But no. What actually happens is that they romanticise the idea of “leaving.”

In their minds, the moment they say, “I’m leaving,” the job is already over—they feel free. And once they feel free, they unconsciously find ways to sabotage the job so that the external reality matches their internal decision.

Changing this mindset has been one of our biggest struggles. But of course, there are reasons behind it. Supporting the household has never been considered a woman’s role. Nor has proving oneself in the workplace. These roles are assigned to men. So women learn these roles later in life, and it takes time for them to internalise them.

A large part of society still does not want women to work or start businesses. Their own mothers don’t want it. Their husbands don’t want it. Their friends don’t want it. Even their children resist it. There are always people clinging to them. So letting go of a job doesn’t feel that difficult in comparison.

What have you observed about solidarity among women?

When women are given the space to form their own communities, they show extraordinary solidarity. We have an association called Biz Bizze, established to support women who face obstacles when trying to find a job or start their own business.

I watch the interaction in its WhatsApp group, and I’m constantly impressed. When a woman needs something, they open their resources to each other with remarkable generosity. They collaborate, act collectively, and support one another beautifully—so long as the right environment exists.

How is your experience as a therapist going? What are you doing?

I truly enjoyed the process of learning during my clinical psychology doctorate, and once I began seeing clients under supervision, I realised I loved the work itself. I felt that I could genuinely be of help to people. At first, it was difficult—I couldn’t leave therapy in the therapy room and return to my own life. The conversations stayed with me, echoing in my mind. Eventually, though, I learned how to set boundaries and leave what was said in the room.

But there is still something that deeply troubles me. Therapy services are extremely expensive—both globally and in Turkey. As a result, only a certain segment of society has access to them. If you don’t have money, you are simply excluded from therapy. In state hospitals, there’s no time for proper psychological support; psychiatrists often can only prescribe medication and send patients on their way. Yet in many cases, psychotherapy alone is enough to ease those problems, without medication.

This reality—therapy being accessible only to those who can afford it—goes against everything I believe in, especially as someone who identifies as a communist. I spent a long time thinking about what could be done. During my doctoral research, I discovered that some countries offer group-based programmes—not group therapy in the conventional sense, but training modules that can be facilitated even by trained nurses. That idea stayed with me.

How?

We work with groups of 10–12 women. We designed four training modules: emotion regulation, mindfulness, stress tolerance, and effective relationships. These modules are based on dialectical behavior therapy. My aim is to train women who can then go on to lead their own groups—essentially a “train the trainer” model. I personally conduct these programmes. We also established an organisation called Meraklı Bilge. Under its umbrella, we run assertiveness camps for women. These programmes focus on assertiveness, self-expression, and communication skills. Sessions can be half-day, full-day, or even two days long. I’m trying to expand this work further.

My broader mission is to find methods that help women discover and reclaim their own power. This is my life’s work. I have been oppressed; I know what oppression feels like. I know the tricks patriarchy has played on me. When I didn’t recognise them, I was more oppressed. I’m still oppressed now—just less so. This is one of the central issues of my life. And I intend to do whatever I can in this area. The training programmes I mentioned are part of this effort, because they also contain elements that help open professional pathways for women.

What factors, for example?

Take assertiveness, for instance. We waste so much time trying to say what we want, what we need, and what we think—if we manage to say it at all. When we do speak up, we get labelled instantly. Before we speak, we carry the anxiety of how we should express ourselves. It’s a waste of time and emotionally draining.

Another issue is emotional regulation. Patriarchy affects us so deeply that even when we continue our work, we often cannot regulate our feelings. Without emotional regulation, we sabotage our own efforts. We express ourselves in ways that aren’t helpful, we prolong emotional states, and we don’t understand what purpose a particular feeling serves. Sometimes when we speak, we don’t know what exactly we should say or what would actually help, and we end up harming ourselves instead.

We have not learned emotional regulation as a society. Our parents didn’t express their emotions in healthy ways, nor did they model that for us. These simply aren’t skills we naturally possess. But if we learn them, we can carve out our own path—especially in professional life. That’s why I’ve been thinking about these issues so much lately.

The groups you’ve formed with women, assertiveness training, Meraklı Bilge… What do you think these will evolve into?

Everything is developing gradually. I don’t yet know what all of this will eventually become. As you know, Turkey doesn’t have an official “social enterprise” status. For instance, B-fit met every criterion of a social enterprise. A social enterprise is essentially a company that identifies a social problem and works to solve it—but through the tools and mechanisms of a for-profit business. Of course, if you establish a foundation, you could also call that a social enterprise, depending on how it operates.

You were 38 when you started studying psychology in America. What would you say to those who think it’s too late to start entrepreneurship or pursue something they desire?

I wouldn’t say anything. Just get up and do whatever it is you want to do. You have only one life. It doesn’t have to go anywhere in particular. If I have fun along the way, that’s a bonus—at least that’s how I see it.