How to Build a Watch Library? (I)

Some may know, watch is not a simple object. However, some of us do not know the timepieces at all, whilst some of us have the wrong information about them. Besides, one cannot know everything. Therefore, human being must constantly read, observe, and understand. If we have a watch library, would it be possible looking at watches from a different perspective?

Photos: Mehmet Çelik

We did not have a watch museum in the past. Likewise, when I think about whether there is a library on watches and time, I cannot find an example for such library. There is no such place. At least there is no such a public place. Well, anyone request for this? It must be. Someday, a watch library should build. Because when it comes to watches people should come to mind such as philosophers who think about time, Marcel Proust swimming in a sea of memories or a stylish hero who takes the Breguet watch of Alexander Pushkin rather than a time machine.

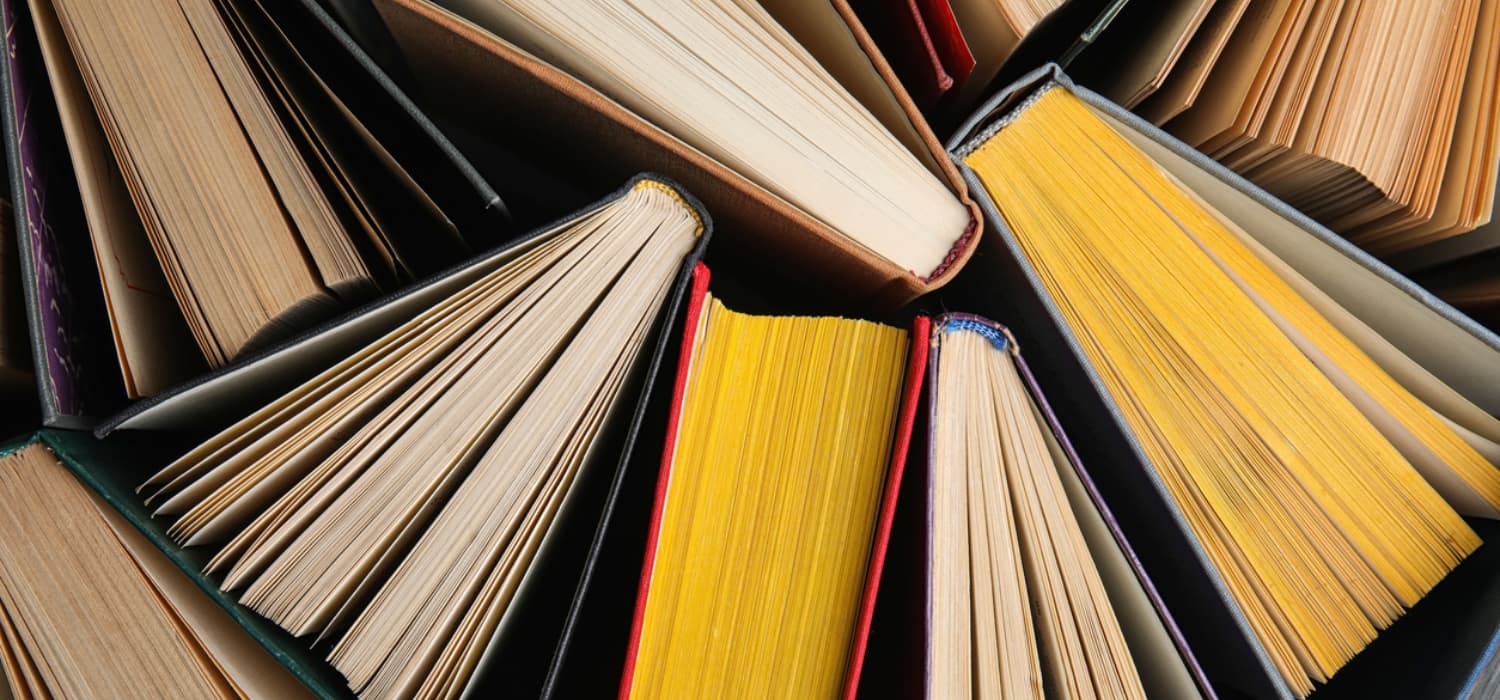

Therefore, library is a must. And a watch library should be overflowing with magazines, and best magazines such as Revolution, Zoom, Watch Plus were published on the subject. Furthermore, Esquire The Big Watch Book, QP, WatchTime, and a unique publication Saatolog continue to publishing. On the other hand, the number of watch books are less than magazines.

While I am looking at my dream watch library, I think of the famous words of Jorge Luis Borges: “Time is a river which sweeps me along, but I am the river; it is a tiger which destroys me, but I am a tiger; it is a fire which consumes me, but I am the fire.” (Labyrinths, 1964)

Watch Books

The magazines are already clear, now let us see the books that should be in a watch library. Of course, books about mechanical watches should be in the front of row in a watch library. Let us begin with most recently published book.

Timekeepers, Simon Garfield, transl: Özge Dinç, Turkuvaz Book, 2021.

When it comes to Simon Garfield, my flesh creeps. Because I had an adventure that the mistake of translating Simon Garfield’s a short article for a magazine. It was extremely tough. The conclusion: I was alienated from English, questioned my Turkish knowledge and was weary of life.

Thanks to Simon Garfield, I almost went back to 2013, when I was afraid of translation, and begging my friends. I think that a book translation must be hell if a magazine article such hard. Simon Garfield’s translators are now heroes to me. That is why, I cannot praise my translator friend Özge Dinç enough. The publishing house that worked with Dinç is incredibly lucky as she is a Turkologist, watch editor of Esquire magazine, and manager editor of The Big Watch Book; so, the editor of the Timekeepers had little work to do. There could not have been a righter person to translate a watch book. (Meanwhile, greetings to those hardworking editors who do not always come across a clean book and are not appreciated!)

Timekeepers tells about many people, including artists, athletes, inventors, composers, directors, writers, photographers, social scientists, and watchmakers. Not just human beings, but also many watch brands are mentioned in the book, such as IWC, Patek Philippe, Breguet, Audemars Piguet, Ulysse Nardin, Rolex, TAG Heuer, Jacob & Co, Mondaine, Victorinox, Christophe Claret, Hublot, Zenith, Harry Winston, Montblanc, Omega, Jaeger-LeCoultre and Vacheron Constantin.

The hero of one of the most interesting stories in the book is William Strachey, who lived in India for a while, had lived more than 50 years of his life in England according to Kolkata time. He had breakfast at teatime, lunch by candlelight in the evening, and had to make precise calculations about other routines of daily life, such as train services, shopping, and bank hours. However, a few years later, things got even more complicated: with Kolkata time moving 24 minutes ahead of the rest of India, Strachey’s time moved 5 hours and 54 minutes ahead of London time.

Timekeepers has a clean translation, no doubt that done with a fair amount of hard work. In almost every part of the book (as in the Baselworld chapter), latest developments were given with footnotes when needed. While I am appreciating the Timekeepers, I expect new translations from the translator, or better yet, new copyrighted works from the author whose one foot is in Switzerland.

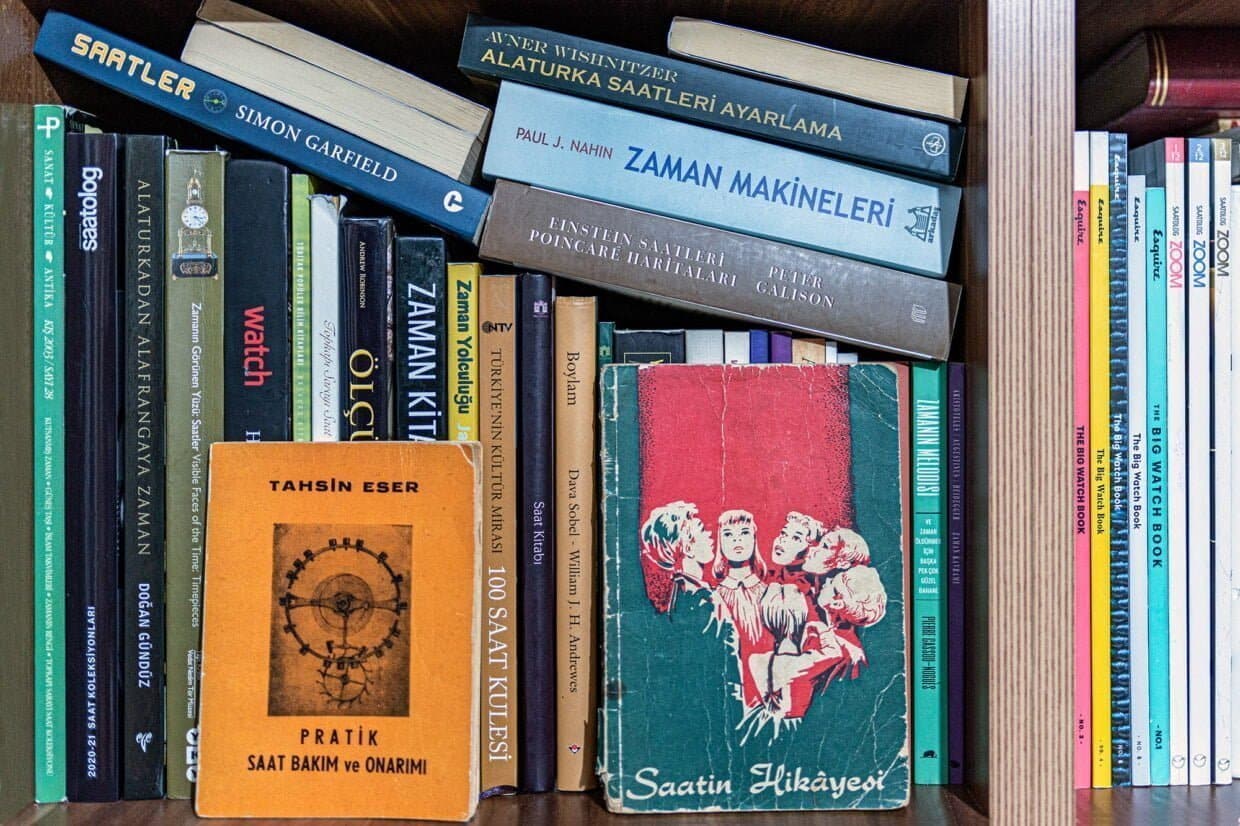

The Watch Book, Şule Gürbüz, TBMM Departmant of National Palaces, 2011.

The name of author is not written on the book cover, yet Şule Gürbüz’s The Watch Book is one of the must-have books in a watch library. The most crucial point is the presence of the author. Şule Gürbüz is a writer who studied art history and philosophy and is an extremely valuable name as a watch repairer for museum palaces, her every article writes about watches and time is at a premium. In the book, there are magnificent articles on Ottoman watchmakers, Turkish watches and time, mechanical watch repair, clock-towers, and Ahmed Eflâki Dede. My favorite article is “Looking at the Watch”, on page 107. A sentence from this article: “When looking at the watch again, all past and future times and all people who ever looked to date are intuited, though not actually seen first and last.”

The Face of Time:Watches, YKY, 2009

An exhibition titled “The Face of Time: Watches” was held at Yapı Kredi Vedat Nedim Tör Museum between March 13 and June 28, 2009. A comprehensive book with the same name as the exhibition was also published at that time.

The introductory article of the book is by İlber Ortaylı, presentation chapters are signed by Şule Gürbüz, from a rare work Wolfgang Meyer’s “The Sun Watches in Istanbul”. In addition to the Şule Gürbüz’s article in this important book, her interview with craftsman Recep Gürgen (p. 149) is one of the unforgettable pages. A perfect start to get know Recep Gürgen.

Topkapı Palace Watch Collection / The Watches That Made World Jealous, 2012

Another exhibition book with great articles. The introductory article is by İlber Ortaylı, and preface is by Shelly Ovadia. Şule Gürbüz also contributes to book with her Edhan Time and Muslim’s Time Perception, How Do Turks Make Watches? and Mechanical Watchmaking articles. The actual part of the book is the catalog of watches exhibited.

It was a magnificent exhibition. From the sound of things, the exhibition area will move, and we will be able to see the watches and more in this book, again in Topkapı Palace, but in a larger area. Craftsmans Recep Gürgen and Şule Gürbüz are working on revive valuable watches.

Longitude, Dava Sobel (Tübitak)

The Age of Discoveries began in 1492. However, it was such a dark time, and setting sail to unknown was the end of many people. When the ships steered for the familiar routes, they were prey to pirates or enemy warships.

Since ancient times, the sailors have been able to calculate the latitude of the sun and known stars by looking at their height above the horizon and the length of the day. Yet, the measurement of longitude lines is not so easy, it depends on time. In order to learn the longitude at a point in the sea, it is needed to know what time it is on the ship and at a known longitude, at that time.

A sailor who knows what time it is at two different points can convert the time difference into distance information. Since 24 hours have passed once our planet rotates around itself, an hour’s rotation corresponds to one twenty-fourth of a day. Since the Earth rotates 360 degrees, this one-hour rotation corresponds to 15 degrees. Each time difference indicates a 15-degree path east or west, that is, 1 longitude range. Each longitude range shows the distance traveled. However, while the longitude range is 111 kilometers at the Equator, it is zero at the Poles. All these difficulties necessitated the development of watches. However, there were other challenges in the way of development. For instance, on a ship that could not stay in the same position in a turbulent sea, the primitive time measuring instruments were also slowing down or stopping. Moreover, the temperature problem experienced by ships navigating between different geographies also affected the watches. In cold weather, the oil of the watch was freezing, and metals were contracting, whilst in hot weather the metals expanded and the oil thinned, it was difficult to determine the longitude with such a tool. The first condition of calculating longitude with using time was knowing what time it was in two different places.

In fact, Christiaan Huygens, who is regarded as the first great watchmaker, had designed some watches for use at sea nearly 100 years before John Harrison, but could not overcome the challenges of producing a reliable and precise sea watch. The conclusion was even famous scientists such as Isaac Newton, Galileo Galilei and Edmond Halley decided that the longitude problem could not be solved without watches, and they thought that measuring the positions of the moon and stars was the most appropriate way.

At long last, in 1714, Longitude Act passed in Britain. According to this act, it was decided that the person who would find a method for the longitude problem with a precision of half one degree (1 degree means a difference of 110 kilometers over the Equator, this large margin of error also showed the desperation of the board) would be offered an unprecedented reward of £20,000.

Gemma Frisius dreamed of using a mechanical watch to find longitude in 1530. However, after 200 years later, this idea was realized by John Harrison, who is a watchmaker born in 1693 and had an intelligence beyond his time. And Longitude tells the story of the watches (H-1 to H-5) produced by John Harrison. A wonderful watch book.

Reading Clocks, Alla Turca: Time and Society in the Late Ottoman Empire, Awner Wishnitzer, transl: Ercan Ertürk, İş Cultural Publications, 2019.

This book, which started as a thesis on time and culture in the Ottoman, later turned into a more comprehensive work of 258 pages (335 pages with Notes, Bibliography and Index sections) with content that goes beyond the academic world. I said, “content that goes beyond academic world” because many curious people, along with me, listened to the author’s speech “Return to Ottoman Time” at Pera Museum, on 4 April 2009.

The introduction of the book is very entertaining, tells the minutes of the Ottoman council members on December 31, 1877, showing that they could not determine the meeting time for the next day. Although these speeches were about the difference between Turkish and European time, they show the existence of much deeper issues for the determination of time. The author says that research about time in the Ottoman Empire is still in its infancy.

It is not a stretch to say the most impressive chapter of the book was “Ferry Stories”, which begins on page 167. Each chapter is important, but I think the “Time for School” and “No Time to Lose” chapters are also interesting.

A Watch for the Sultan / European Clocks and Watches in the Near East, Otto Kurz, transl: Ali Özdamar, Kitap Publishing House, 2005.

A Watch for the Sultan describes the period after the invention of the first mechanical watch in the 1300s, as a result of the development of time measurement studies in the West, which were first raised in the East but then forgotten. The book talks about the only exception was Sultan Mehmed the Conquer that for more than two hundred years in a period no one showed any interest in newly invented time measuring instruments. After the peace treaty in 1477, Fatih asked the Venetian seigneur to send him a glass craftsman who had the ability to make glasses and a watchmaker who could make alarm clocks, and a good painter. On October 2, 1531, in Venice, Marino Sanudo seen a gold ring with a watch inside. Despite its tiny size, the watch was in perfect working order, showing the time and announcing the time by ringing at the beginning of the hour. We have learned from a letter that this watch was purchased by Suleiman the Magnificent, and this watchmaker was Giorgio Capobianco from Vicenza. Twelve men were needed to move the next watch, which reached Sultan Suleiman, to the supply room. The machine that the apostles brought in the autumn of 1541 combined a watch with a planetarium, and showed the movements of the Sun, Moon and planets thanks to a complex mechanism.

Whereas, around three hundred years ago, a planetarium had traveled in the opposite direction as a gift from a sultan to an emperor. In the following centuries, it has been traditionalized for Western emperors to present various watches to the Ottoman Sultan and courtiers. The timepieces were in a great demand in the Ottoman market. Therefore, many pocket watch shops were opened in Galata in the 17th century. These shops were opened by craftsman from the West. In the next century, English pocket and wall watches would be popular in the Ottoman market.

The book also includes many interesting information, for example, watches with the portraits of Sultans were started producing for the first-time reign of Sultan Abdülmecid.

The Time Machine / Clocks and Culture: 1300-1700, Carlo M. Cipolla, transl: Tülin Altınova, Kitap Publishing House, 2002.

The Time Machine is a book based on questions and answers. Carlo M. Cipolla explains that the watch has a cultural dimension beyond being a technical tool with questions such; “Why did the first mechanical watches appear at the same time as the end of the 13th century and the beginning of the 14th century? Why were the timepieces developed in Europe? Why was the watch viewed as a toy in China? Why did the Japanese develop their own unique watches?”

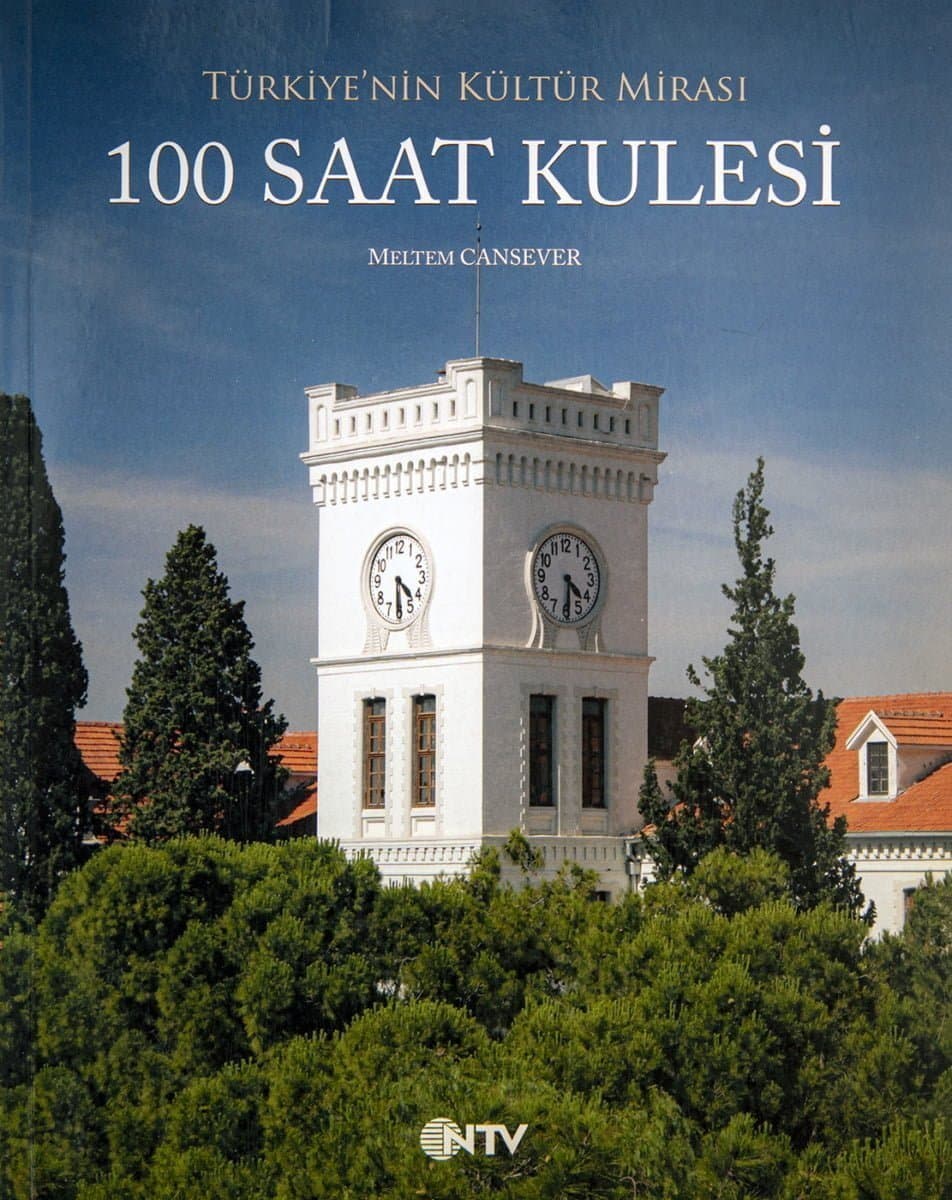

The Cultural Heritage of Turkey: 100 Clock Tower, Meltem Cansever, NTV Publ., 2009.

One of the best aspects of this book is “Clock Towers As Mechanically” which is written by Şule Gürbüz. The book talks about the clock tower Turkey. It does not inspire enthusiasm to see these tower, yet it fills the void on this subject.

Time from Alla Turca to Alafranga, Doğan Gündüz, Ege Publ., 2015.

An important work that I wish had not been printed on cast coated paper. The book, which has a successful design with the subtitle “Mechanical Watches in the Ottoman Empire”, contains high quality visual materials. In the work, parallel topics are talked in Otto Kurz’s A Watch for the Sultan. Thomas Dallam’s sad story of the mechanical clock-organ (p. 75) is a chapter that I read again and again.

National Palaces Watch Museum (The Grand National Assembly of Turkey Publications, undated catalogue)

According to the introductory article of the catalog, unsigned but stylistically understood to belong to Şule Gürbüz, National Palaces Watch Collection has 193 of the 294 watches at Dolmabahçe Palace. These watches, most of which belong to the second half of the 19th century, are collected in two separate sections as European and Ottoman. I think that the watch museum in Dolmabahçe Palace, which housed exceptionally beautiful timepieces, is under-appreciated. Each timepiece in the collection is fairly a different world.

Practical Watch Maintenance and Repair, Tahsin Eser, 1974.

The author says that he has been interested in watchmaking since his early ages, after he had retired from TCDD Izmir Accounting Directorate, where he worked for thirty years, started to repair watches in his atelier called as Eser Saatçi in Kadıköy, Istanbul. After working on this field for 18 years, he wrote this small but invaluable book. The book includes practical information on watch repair.

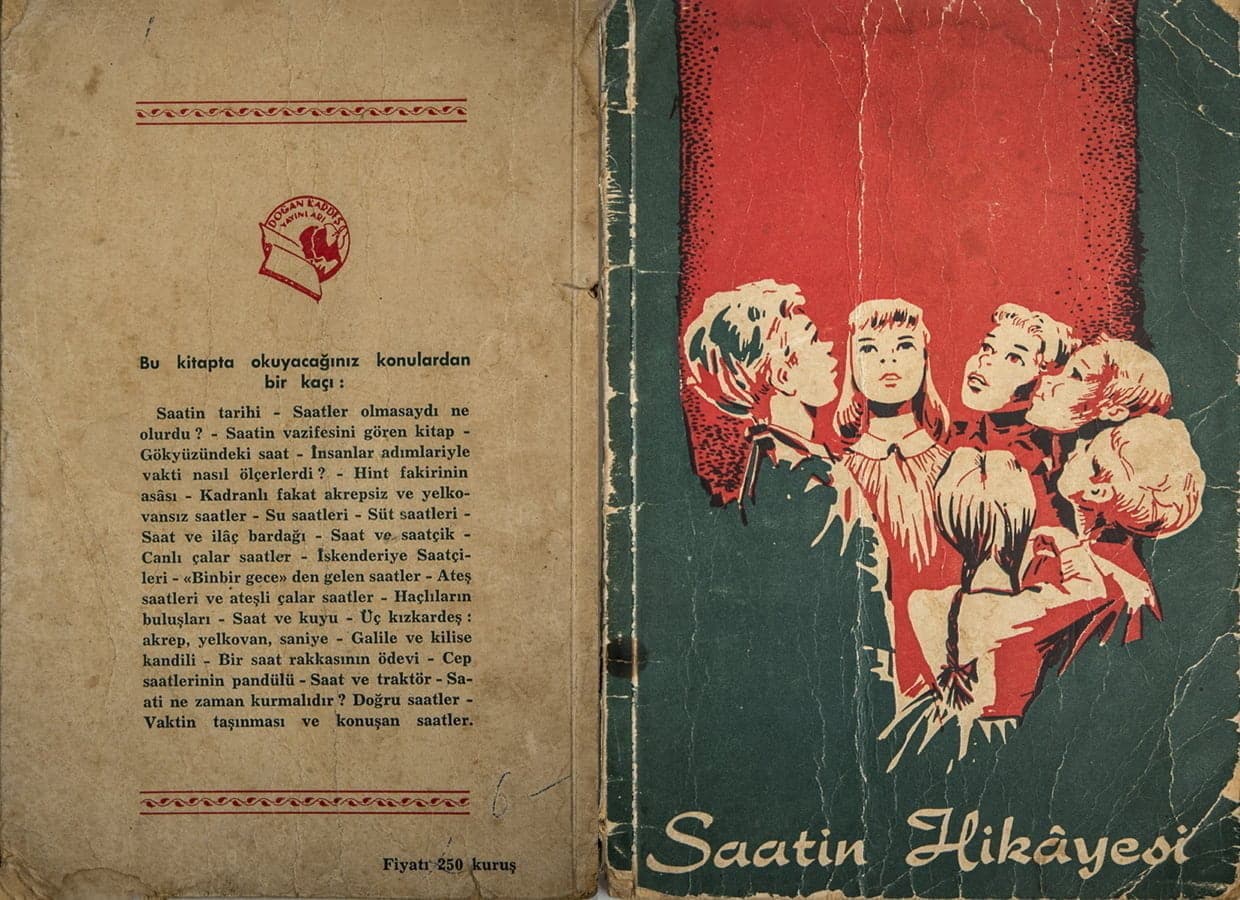

The Story of The Watch, Hasan Ali Ediz, Doğan Kardeş Publ., 1959.

Another magnificent book… It is hard to believe that the book was written for children. The back-cover blurb includes several interesting topics: the history of the watch. What would happen if there were no watches? The book that serves as a watch. The watch on the sky. How did human being measure time with their steps? The timepieces with dial but without hour and minute hands. Water watches. Milk watches. The watch and medicine glass. Living alarm clock. Alexandria watchmakers. The timepieces from 1001 arabian nights. Fire watches and fiery alarm clocks. The three siblings: hour, minute, second. The homework of a pendulum clock. The pendulum of pocket watches. When to wind a watch?

Watch Plus, Horology Encyclopedia Special Issue, October 2016

The most important and last issue of Watch Plus magazine’s 10-year publication life looks more like a large book than a magazine, and it is far from the classic magazine format with its 384 pages. It was incredibly sad that the magazine was closed, my only consolation was that I was a small part of it. Ömer Sevil and his colleagues designed the last issue as a thematic encyclopedia. The magazine consists of two chapters as “Horology Legends” and “The Brands”. In the introduction, the short but touching article by Ömer Aydın, who is the third generation manager of Tevfik Aydın Saat, is particularly important.

Other Important Issues on This Subject::

- Objects of The Daily Life in the Ottoman Empire, Şinasi Acar, YEM Publ., 2011

- From the History of Watchmaking to the Watch Collection, Ed. Filiz Çağman (Akbank Publ.)

- Sundial Construction Guide, Ahmed Ziya Akbulut (Bir Yıl Kültür Sanat Publ.)Rubu Board User Guide, Ahmed Ziya Akbulut (Bir Yıl Kültür Sanat Publ.)

- Ottoman Sundials, Assoc. Prof. Dr Nusret Çam, Ankara, 1990.

- Safranbolu Clock Tower and Timekeepers Symposium (Proceedings Book, Safranbolu Municipality)

- Anatolia Clock Towers, Hakkı Acun

The next article: The Time Machines: Time Oriented Books in Thought, Art and Literature