The Worst 20 Minutes of My Life

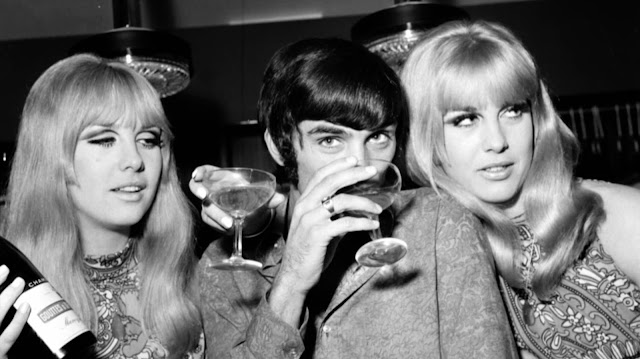

“If you asked me, ‘Would you rather dribble past three players, score from 40 yards out against Liverpool, and make the crowd roar, or spend a night with Miss World?’—well, that would be a tough choice. I’m lucky because I’ve done both. But one of them was in front of 50,000 people,” said George Best.

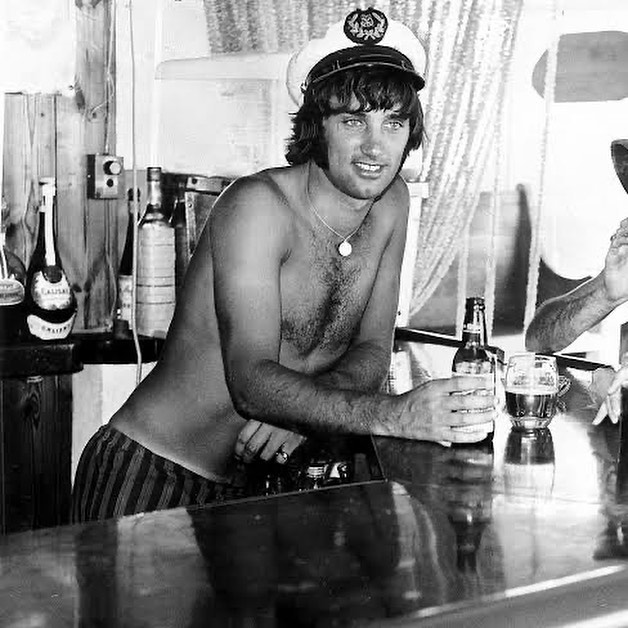

Life, in many ways, resembles football. George Best’s life was football—complete with triumphs, downfalls, and all the pain in between. Born in Belfast, he was only fifteen when he first joined Manchester United’s training session and made his teammates regret ever calling themselves footballers. He was George Best: a prodigy, a playboy, an alcoholic—and a legend.

What set him apart from every other gifted player before him was something unprecedented: he was football’s firstmodern superstar. No one had ever been as “famous” as George Best. No footballer had ever been so relentlessly followed by journalists, women, and fans. And no one before him had ever fallen from such dazzling heights.

His genius on the field was matched only by his appetite for nightlife, women, and alcohol. Every step he took became gossip. He was, in a sense, what today’s footballers are on social media—only decades before Instagram existed. England, and a good part of Europe, became a living app orbiting around him. Whatever he did, he was watched. And people watched him a lot.

When United’s manager Sir Matt Busby first received the scout’s message about a promising teenager, the note simply said: “We think we’ve found a genius.” Excited, Busby asked, “Really? Who does he play like?” The scout’s reply would turn prophetic: “He’s like no one we’ve ever seen before.”

The fifteen-year-old boy from Belfast was invited to a trial. It took Busby barely five minutes to be convinced. The seasoned United players, known for their toughness, tried everything—kicking, pulling, fouling—to dispossess the frail boy. But Best danced through them like the wind. His opponents could only see him from behind as he flew past, both the ball and his body untouched. Even fouling him was difficult; he was too quick to catch. The lucky ones in the stands saw both his face and his back—especially the women, many of whom fell instantly in love.

A few years later, after a sensational performance against Benfica in the European Cup, female fans stormed the pitch with scissors in hand, desperate for a lock of his hair.

This wild child from Belfast was not only gifted—he was handsome and aware of it. “If I had been a little uglier, neither Maradona nor Pelé would be remembered,” he once joked. By the time he was seventeen, he was England’s most famous man after the Beatles. But his fame wasn’t just about looks or mischief—it was the electricity he radiated on the field.

Even people who don’t follow football today know David Beckham or Cristiano Ronaldo. Both wore Manchester United’s number 7 jersey. But before them, number 7 was just a number. George Best was the one who made it sacred. By the time he took it off, it had become a symbol.

In 1965, Best almost single-handedly carried United to a championship. When he left the club at 27, the team collapsed and was relegated soon after. They would wait 26 years for another league title—until Eric Cantona’s arrival—and 31 years for their next European Cup.

Best burned as brightly as a star could burn. Every club in England wanted him. He, however, wanted only more nightclubs. After the 1965 title came another in ’67—and more alcohol, more women, more goals. The ’68 season brought a European Cup, and with it, even more chaos: more women, more drinks, and now gambling. When asked years later what happened to all the money he earned, Best replied with perfect irony: “I spent 90 percent of it on women and alcohol. The rest I wasted.”

He often repeated one of his most famous lines: “If you asked me, ‘Would you rather dribble past three players, score a goal from 40 yards against Liverpool, and get the crowd on their feet, or spend a night with Miss World?’ it would be a tough choice. I’m lucky because I did both. But one of them was in front of 50,000 people.”

He wasn’t exaggerating. In his 59 years of life, Best reportedly slept with more than 500 women and destroyed two livers—ruining the second one after a transplant. “In 1969, I gave up alcohol and women,” he once said. “It was the worst 20 minutes of my life.”

His stubborn streak—the same one that made him a genius on the field—followed him everywhere. It surfaced in 1976 when Northern Ireland faced the Netherlands. Though widely regarded as one of the best players in the world, Best was often overlooked because his small nation rarely qualified for major tournaments. Asked before the match, “Who’s better, you or Cruyff?” he replied, “Who do you think’s better when I score five goals against him?”

And in the match, when he first got the ball, instead of charging toward the goal, he approached Cruyff, slipped the ball neatly through his legs, raised his hand in a victory sign, and carried on dribbling.

By 1974, after ten years in United’s number 7 shirt, the beautiful, unruly boy from Belfast was an alcoholic, a gambler, and a man who skipped training. Hoping to reinvent himself, he moved to America—but what he sought there was not redemption. It was more of the same: more women, more alcohol, more casinos. When that wasn’t enough, he moved to Hong Kong, then considered the world’s gambling capital, and joined three different clubs—spending far more time in casinos than on the pitch. At 37, he finally took off his jersey for good.

After football, Best tried commentary to make a living, having squandered his fortune. His life had become a cautionary tale. From his hospital bed, his last words, printed across the front pages of British newspapers, read: “I beg God—no one should die like me.” He had lived fast, risen fast, and crashed fast. That’s what made him football’s first true modern celebrity. The fans who once carried him on their shoulders, the women who once chased him with scissors, and the reporters who never left him alone—all now looked at him with pity and faint disgust. Yesterday’s hero had become today’s tragic figure.

When George Best died in 2005, both England and Ireland came to a halt. The plane that carried his body to Belfast and the airport where it landed were renamed in his honor. Today, it is still George Best Belfast City Airport. Within a year of his death, the Central Bank of Northern Ireland printed a million George Best stamps—sold out in five days. More posters of Best were sold than of any rock star of his era, and journalists earned the highest royalties in magazine history from chasing his image.

Hundreds of thousands of fans—many too young ever to have seen him play—applauded him until their hands hurt at tributes before matches. Stadiums wept for him. Of the hundreds of women in his life, he only married twice—both times “offside.” His will to his only legitimate son consisted of three words: “Don’t become a footballer.”

Pelé once said, “He was the best footballer I ever saw.” Best, in turn, said of Cantona, “I’d give up all the champagne I ever drank to play just one game with him.” At Best’s funeral, Cantona completed that exchange with a line of poetic generosity: “In his first training session in heaven, he moved to right wing and turned God’s head at left back. I just hope he saves me a spot on his team. On Best’s team, not God’s.”

That was George Best—an immortal who made football look like art and chaos look like charm. He wasn’t the greatest footballer in history simply because he didn’t want to be. He wanted to live, to feel, to burn. He crammed into one short, dazzling life what others could barely fit into a century.

And perhaps that was his final dribble—past all rules, all limits, and even time itself.

Luiz Nazario Ronaldo: The Story of How a Knee Cap Became a Phenomenon