Luiz Nazario Ronaldo: The Story of How a Knee Cap Became a Phenomenon

Only his own knee cap could stop the man no one else could. This is the story of how Luiz Nazario Ronaldo became a phenomenon.

On November 21, 1999, perhaps the most creative compliment he ever received was spoken: “He’s not human. He is a herd.” With the ball at his feet, he charged at defenders with astonishing speed, resembling a stampede of wild bison. Dust rose as he ran, and if his incredible pace wasn’t enough, he could halt with the agility of a cheetah, twist in the opposite direction, and remain untouchable. But then, suddenly, he stopped. He collapsed in pain.

Clutching his right leg, he stared at his kneecap through tears. The unstoppable “herd” was defeated by his own knee. Carried off on a stretcher, he left players from both teams watching with sorrow. It was the legacy of an injury that began in adolescence, caused by pressure on the cartilage of his knee. Long barefoot hours kicking the ball in Rio de Janeiro’s poor neighborhoods had contributed, as had the relentless strain he put on his body through his extraordinary speed and agility.

Luckily, the diagnosis was not catastrophic. After several months of rehabilitation and a minor surgery, he returned in April 2000 for the Italian Cup final’s first leg against Lazio. Entering in the 55th minute, his comeback electrified the stadium and those watching on TV. All eyes followed him. He touched the ball, accelerated, accelerated, accelerated. The familiar rhythm of his signature moves filled the pitch, and fans savored his presence once again. As he picked up speed, the roar grew louder. Then, without warning, he stopped. The man who could not be stopped had halted himself for the second time in five months. He crumpled to the ground, crying in pain once more. But this time, he wasn’t alone—fans in the stands, teammates, and viewers around the world wept with him. In history, perhaps only a kneecap could carry such dramatic weight. This injury was far worse. The tendon previously repaired by surgery and stitches had now completely ruptured. He was stretchered away. Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, the Catalan sociologist and devoted Barcelona fan, remarked: “If football is a religion, today it has lost its god.”

The curtain fell, the lights dimmed, and the crowd dispersed. Was it all over? No. The reason for starting in the middle of this story is that this was the turning point. Now let’s rewind and return to the early years of Luiz Nazario Ronaldo, one of football’s greatest ever players.

In Brazil, games in the alleyways began at dawn and ended only with nightfall. Barefoot children gave rhythm to the ball, filling the sky with melodies. One of the sweetest came from Ronaldo’s feet. A childhood friend recalled years later: “When we sat down from exhaustion, Ronaldo was still chasing the ball. He had endless energy. Football wasn’t just a game for him—it was like breathing.” That boundless drive took him to Cruzeiro at just 16.

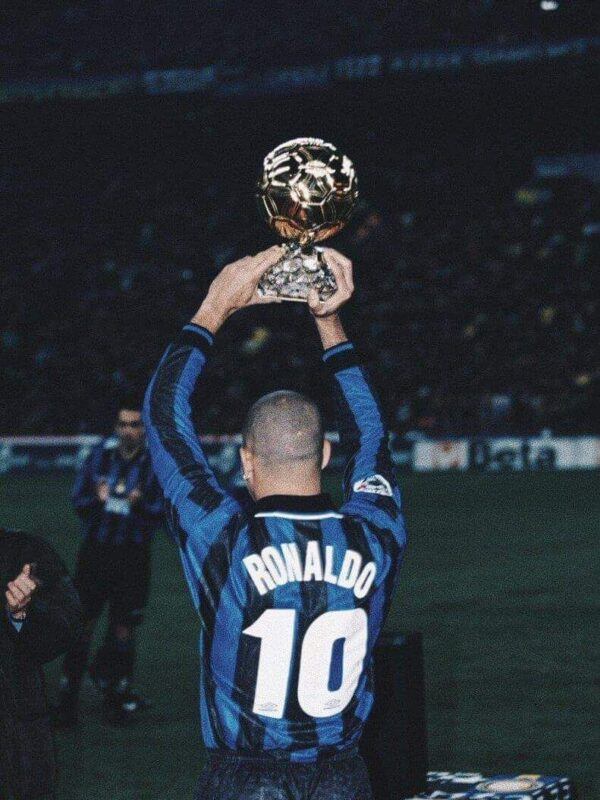

When he scored his first professional goal, the crowd knew instantly: this boy was a star. His speed, control, and technique were unmatched. Even his early statistics proved it: 20 goals in 21 games at 16; 24 in 26 the following year. By 18, he had crossed borders to join PSV Eindhoven, where he netted 36 goals in 35 matches, then 19 in 21 the next year. Exhausting to read, but effortless for him. At 20, wearing Barcelona’s jersey, he scored 47 goals in 49 games and was named World Footballer of the Year. At 21, he joined Inter, scoring 34 goals in 47 games in one of the toughest leagues in the world, while also adding 30 goals in 44 appearances for Brazil, including five in the World Cup. By 21, he had tallied 208 goals in 244 matches, earned two FIFA World Player of the Year titles and one Ballon d’Or, alongside three championships, a World Cup, and two Copa Américas. Praise followed him everywhere. Sir Bobby Robson, then Barcelona’s coach, said: “I’ve never seen a striker like him. When he gets the ball, not only the opponents but even we wait with bated breath to see what happens.” Robson, known for his sharp wit, had seen countless stars—but Ronaldo was unlike any before.

Then came November 21, 1999—the day already described. What was thought to have healed by April 2000 resurfaced with horrific violence. Brazilian physiotherapist Petrone called it “the most severe and terrifying football injury I’ve ever seen.” Endless treatments followed: lonely, painful nights, a knee that ached relentlessly, and a man who once moved like the wind now leaning on crutches.

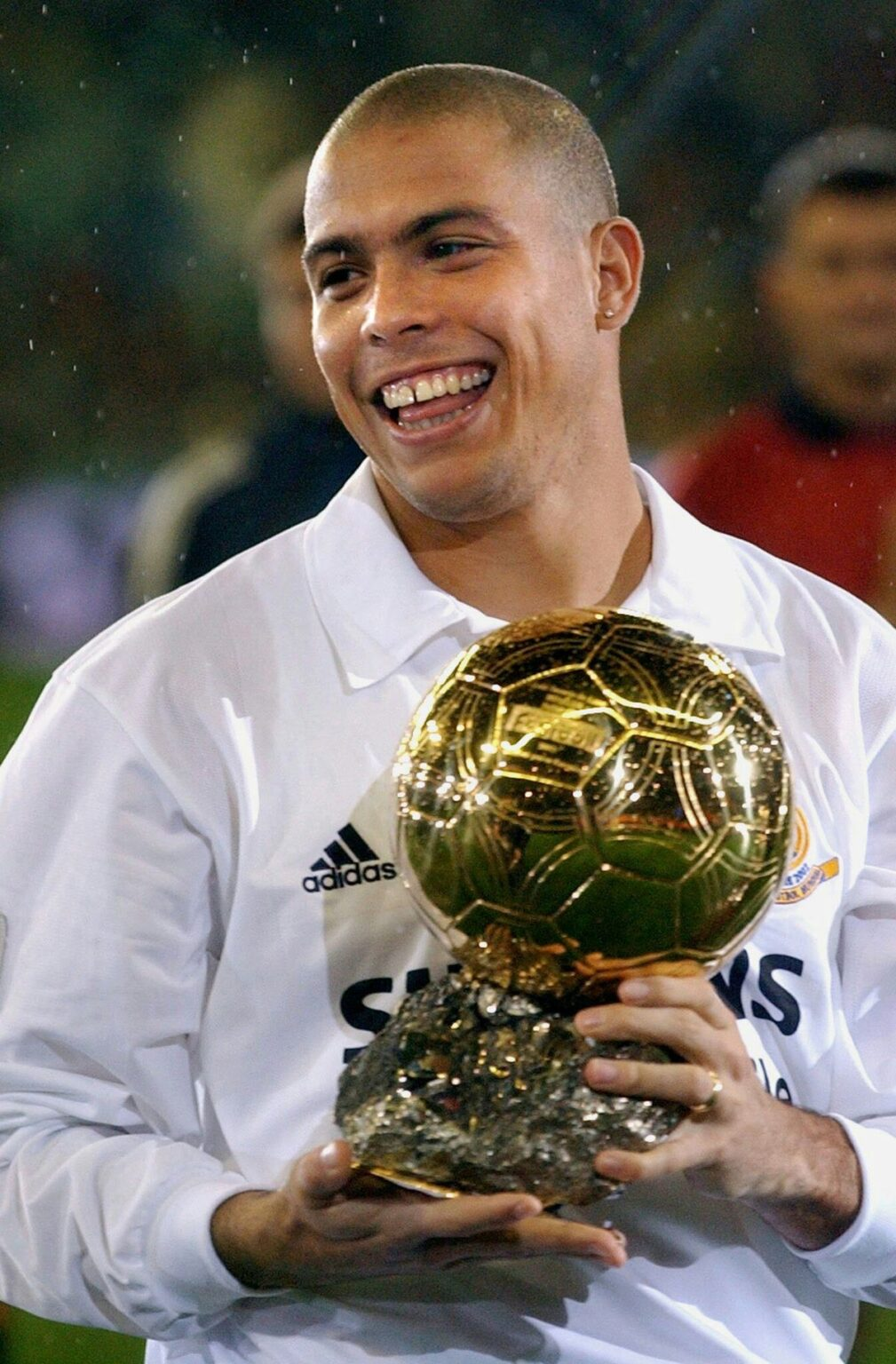

The 2002 World Cup, Turkey’s last appearance, brought Ronaldo back to the world stage—haircut and all. But his goal was more than fashion: it was redemption. Many doubted he could even walk, yet there he was, playing for Brazil. Turkey, too, felt his brilliance—knocked out in the semifinals by one of the simplest goals of his career. He struck the ball awkwardly, almost like a child just learning to kick. No one, not even goalkeeper Rüştü Reçber, expected it. That goal sent Turkey to the third-place match and Brazil to the final, where Ronaldo scored twice against Germany. He finished the tournament with eight goals, earning the Golden Boot. Oliver Kahn, the tournament’s best goalkeeper, admitted: “I was the best goalkeeper there, but when I looked into Ronaldo’s eyes in the final, I knew what would happen.” And it did.

Two years before, Ronaldo needed crutches. By 2002, he was dazzling again, joining Real Madrid that summer. On a Champions League night against Manchester United, he scored a hat-trick so audacious that Old Trafford rose in applause, applauding him for minutes. Just two years after his kneecap was displaced by ten centimeters, he was running again—like that unstoppable herd. Zidane summed it up: “Ronaldo was more than a striker. When he touched the ball, everyone’s face lit up. Football was more beautiful with him.”

But years of injuries, surgeries, weight gain during layoffs, and age eventually caught up. After five glorious years at Real Madrid, he returned to Italy with Milan, then back home to Brazil with Corinthians, where he was welcomed as a hero. Three seasons later, at an emotional press conference, he confessed: “My body is telling me to stop.” In tears, he accepted what his knee had decided long before. In April 2000, his injury left even Inter’s captain Zanetti in despair: “Ronaldo was writhing in pain. We all ran to him. It felt like losing not only a great footballer, but a friend.” In 2011, millions felt the same when he retired. Ronaldo had lost his lifelong friend—the ball. Yet the streets remembered. Because no one had ever played like him.

That phenomenon was Ronaldo. Just Ronaldo. Every Ronaldo who came after would need two names. The only true Ronaldo was him. Born 49 years ago today, on September 18, 1976, his name, his goals, his haircut, even the copyright battles that left him marked only as “No. 9” in football video games—all remain unforgettable. Today, when someone says “No. 9,” the world knows exactly who they mean. And really, how much more of a phenomenon can a knee be?