The Art Market in Times of Crisis

These days, a single question echoes across the art world: Should the record-breaking auction sales be cause for celebration, or are they the early tremors of an approaching collapse?

There are moments in the art market when numbers begin to overshadow logic. After an extraordinary week in November at the auction houses, art historian and academic Burak Yiğit Aydın made a striking remark on his YouTube program Eller Kadir Kıymet Bilmiyor (“Hands Don’t Know Their Worth”): “For the first time in world history, three sales records were broken in a single week. One after another. And this is not a good sign.” His follow-up comment sharpened the picture even further: “These records always surface before major crises —major economic crises and global upheavals.”

Auction houses are more than luxurious marketplaces; they often serve as stages for power, confidence, and at times, unrestrained appetite. Behind the crystal glasses, the polite applause, and the slow-motion bidding wars lies a persistent, almost whispered question: Why is so much money flowing now?

A look back at history tends to bring us to the same familiar conclusion. The art market reaches fever pitch during periods of heightened economic optimism, when wealth accumulates rapidly in select hands. Prices surge, records topple one after another, and what was once seen as an “exception” suddenly transforms into the “new normal.” And more often than not, these scenes play out just before a storm breaks.

So let us briefly revisit some recent sales that, as Burak Yiğit Aydın notes, have turned into a form of “portable wealth insurance.”

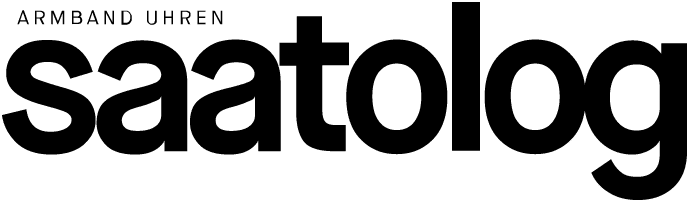

The Japanese Dream and Van Gogh

One of the most memorable scenes in the recent history of extravagant, almost irrational luxury unfolded on May 15, 1990. Japan’s economic bubble had expanded to such proportions that money itself seemed to have lost its weight and meaning. In this atmosphere, Vincent van Gogh’s Portrait of Dr. Gachet sold at Christie’s in New York for a staggering $82.5 million. The buyer was Japanese businessman Ryoei Saito—an amount that instantly made the painting the most expensive artwork in the world at the time.

But the story did not end with a single record-breaking purchase. Just two days later, Saito acquired Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s Bal du Moulin de la Galette for $78.1 million, leaving behind, within a span of 48 hours, a fortune that would go down in art-market history. In today’s currency, the total amount spent on these two works corresponds to roughly $327 million.

These acquisitions became emblematic of how the art market can be swept into speculative frenzy at the height of an economic bubble. At the peak of the madness came rumors that Saito had asked for the Van Gogh to be cremated with him upon his death. And yet, when Japan’s bubble burst soon afterward, it did not take long for these astronomical auction prices to collapse just as dramatically as they had risen.

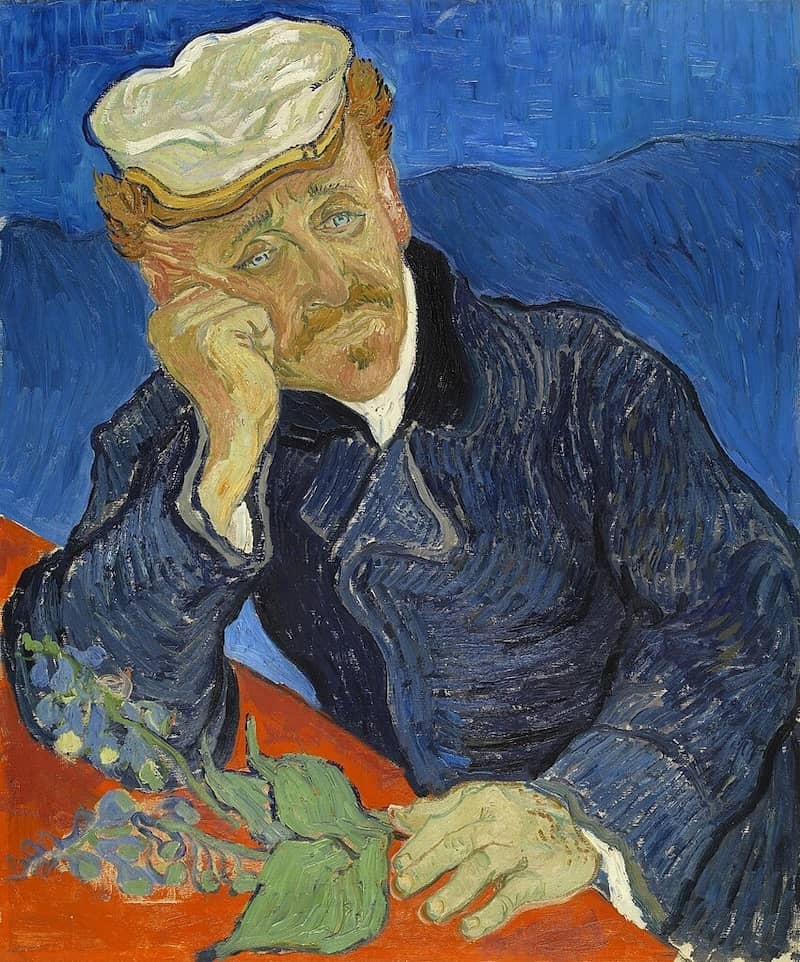

Jackson Pollock – No. 5, 1948 & Willem de Kooning – Woman III

The year 2006 became a striking display of how dangerously intertwined modern art had become with the market. In November, film producer David Geffen sold Jackson Pollock’s Number 5, 1948 for approximately $140 million in a private transaction—at the time, the highest price ever paid for a painting. Just two weeks later, Willem de Kooning’s Woman III changed hands for $137.5 million, marking the second major transfer from the same collection in an astonishingly short span.

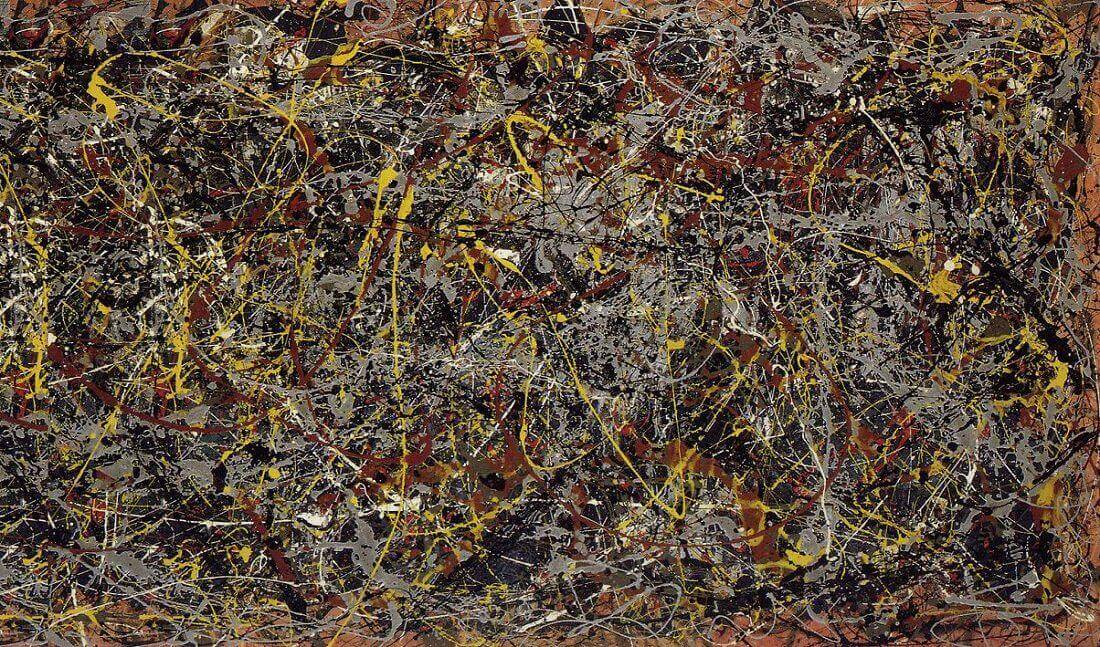

These record-breaking sales did not appear out of nowhere; the groundwork had been laid years earlier. In June 2004, collector Ronald Lauder acquired Gustav Klimt’s portrait Adele Bloch-Bauer I for the Neue Galerie in another private deal worth $135 million. This purchase created a psychological rupture in the art market, as it was the first modern masterpiece to surpass the $130 million barrier.

The Pollock and de Kooning deals demonstrated that this figure was no longer an outlier but had become the new baseline. Coincidence? Hardly. These transactions coincided with the peak of the U.S. housing bubble, a moment when confidence—and speculation—ran unchecked. The financial crisis that erupted soon afterward would reveal that the art market, too, was swept up in the same intoxicating optimism. The canvas may have been small, but the meaning—and the inflated price—was far larger than it could ever contain.

The Most Expensive Symbol of Power of Our Time: Leonardo da Vinci and Salvator Mundi

In the fall of 2017, the Renaissance’s heaviest icon stepped into the global spotlight. Salvator Mundi, attributed to Leonardo da Vinci, shattered every existing record when it sold for $450.3 million at a Christie’s auction in New York on November 15, 2017. The bidder on the phone was Saudi Prince Badr bin Abdullah, purchasing the work on behalf of Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, a detail never officially confirmed, yet widely accepted as fact.

What made this record extraordinary was not only the final price but the dramatic trajectory that led to it. When sold in London in 1958 for just £45, the painting was believed to be the work of one of Leonardo’s students. After a restoration, it changed hands again in the United States in 2005 for $1,175. Then rumors began to circulate that the painting might actually be an authentic Leonardo—a possibility that catapulted it into a completely different realm. In 2013, Russian billionaire Dmitry Rybolovlev acquired it for $127.5 million; four years later, the famous hammer fell again, this time for nearly half a billion dollars.

This sale did not occur on the cusp of an imminent crisis. The global economy at the time was still buoyed by optimistic growth narratives. Yet for many observers, Salvator Mundi became the quintessential symbol of a new era—an era in which art had fully transformed from an aesthetic experience into a financial instrument and a tool of geopolitical display. A painting once overlooked had become one of the most expensive emblems of power in our time.

Alberto Giacometti – L’Homme au doigt (Pointing Man)

Although it may appear overshadowed by record-breaking paintings, the sculpture market has also been swept up in the same whirlwind. In May 2015, Alberto Giacometti’s slender bronze figure L’Homme au doigt (Pointing Man) sold for $141.3 million at Christie’s, earning the title of the most expensive sculpture ever sold. The result slightly surpassed its pre-auction estimate of around $130 million, and it was soon revealed that the piece had entered American billionaire Steve Cohen’s collection.

This sale also broke Giacometti’s previous record; in 2010, his Walking Man I had fetched $104 million. And the momentum did not stop there. In the very same week, in the very same auction room, Pablo Picasso’s Les Femmes d’Alger (O) sold for $179 million—setting a fresh benchmark for paintings. The spring of 2015 became etched in memory as a moment when records were shattered one after another, in both canvas and bronze, under conditions of abundant liquidity and seemingly limitless market optimism.

A critic’s remark about auction houses from that period captured the atmosphere perfectly: money was flowing freely, while creativity, quietly and almost imperceptibly, was slipping into the background.

And now, let’s turn to three recent sales that have been at the center of contemporary art market debates:

Second Most Expensive Work in Auction History: Gustav Klimt – Portrait of Elisabeth Lederer

On November 18, 2025, New York witnessed a staggering moment. Gustav Klimt’s Portrait of Elisabeth Lederer sold for $236.4 million at Sotheby’s, setting a new auction record for the artist. The work came from the estate of collector Leonard Lauder, who had passed away only a few months earlier at the age of 92. With this sale, the painting became the second most expensive artwork ever sold at auction, surpassed only by Leonardo da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi.

Rumors that the buyer was Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, President of the United Arab Emirates—and that the painting might join the collection of the newly opened Zayed National Museum in Abu Dhabi—served as a reminder that such acquisitions are often tied less to aesthetic taste and more to cultural prestige, soft power, and nation-branding.

Before Klimt’s sale, the second-place position behind Salvator Mundi belonged to Pablo Picasso’s Les Femmes d’Alger (Version O), which sold for $179.4 million at Christie’s New York in May 2015 and held that rank for many years.

The Most Expensive Work by a Female Artist: Frida Kahlo – El sueño (La cama)

Barely had the echo of the Klimt hammer faded when the spotlight shifted to Frida Kahlo. On November 20, 2025, Kahlo’s self-portrait El sueño (La cama) sold for $54.7 million at Sotheby’s New York. This price not only shattered Kahlo’s personal auction record but also set new milestones for both female artists and Latin American art broadly. The sale is still fresh, and the market is actively absorbing its implications.

Sotheby’s initial commentary emphasized the convergence of rarity and highly competitive bidding as the key drivers behind the result.

The auction house also announced that the buyer wished to remain anonymous, in keeping with standard confidentiality practices.

Japanese Print Art Record: Katsushika Hokusai – Under a Wave off Kanagawa (The Great Wave)

While New York auction rooms thundered with record prices, another tremor emerged from the Asian market. On the evening of November 22, 2025, at Sotheby’s Hong Kong, all 125 works in the “Masterpieces of Asian Art” sale from the Okada Art Museum collection found buyers, reaching a combined total of HK$688 million. At the heart of the event was one of the most iconic images of Japan’s Edo period: Katsushika Hokusai’s The Great Wave, from the Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji series.

Estimated at HK$5–8 million in Sotheby’s catalogue, the woodblock print sold for HK$21.7 million (about US$2.8 million), setting a new world record for a Japanese print. Only around 130 impressions, dating to around 1831, are known to survive today. Its museum provenance and exceptionally well-preserved condition transformed its rarity into measurable value. When scarcity, historical weight, and distinguished collection history align, the market reaction is instantaneous—this time, the wave truly swept everything in its path.

This sale is also interpreted as evidence that the Asian market is becoming an increasingly powerful center for high-quality works. The compass needle may indeed be shifting—ever so slightly—from West to East. But for some, the scene also echoes the Japanese spring of 1990.

In November 2025, the market’s barometer spiked sharply for a moment. And inevitably, we return to the same persistent question: Why so much money now?

These three sales do not yet provide a definitive forecast. Are we on the brink of a storm, or merely witnessing a period of consolidation within the market itself? Time will offer the answer—and perhaps sooner than expected.

Let’s close this article with a line from Burak Yiğit Aydın, since we opened with one of his remarks. It captures the core truth of the art market in its simplest form: “Rich people sell, richer people buy.”

Opening photo: Eduardo Munoz Alvarez / Getty Images