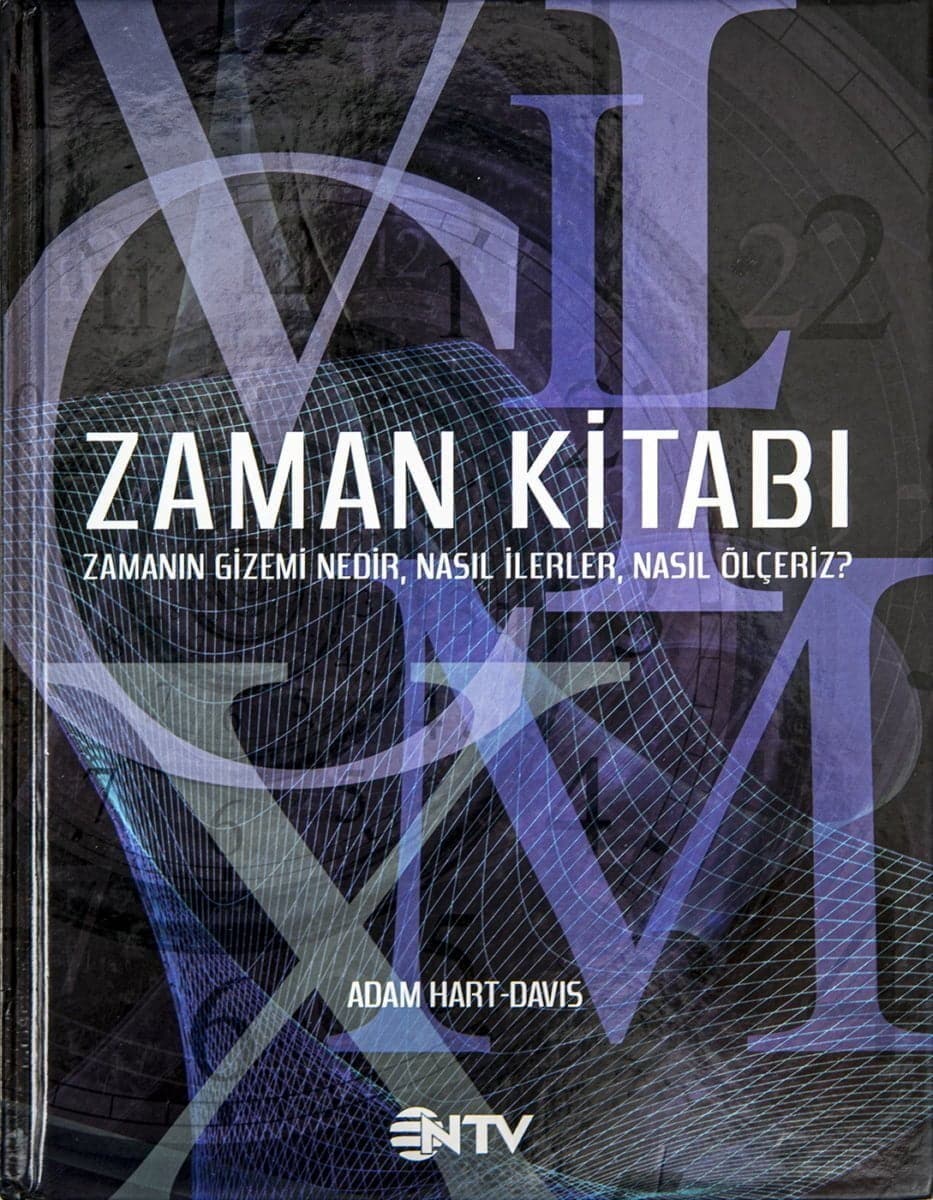

Books Focusing on Time in Thought, Science, Art, and Literature

In the previous article, I introduced some books that directly talk about watches, especially mechanical watches as an object, for those who want to set up a watch library. Now, there are some eye-opening books about the time that I think should be in the library of a haute watch enthusiast.

Pip Pip: A Sideways Look at Time, Jay Griffith, translation: Ertuğ Altınay, Ayrıntı Pub., 2003.

Pip Pip: A Sideways Look at Time is an effective and stimulating work. Jay Griffiths traveled the world for Pip Pip: A Sideways Look at Time and wanted to explain that time is highly political, that there is not just one time on earth. In other words, there are many understandings of time that we cannot even imagine. The author says that the concept of time, which the modern West embraces and imposes, is a hidden keystone of cultural sovereignty.

The criticisms that start at the beginning of the book and may give a shock to the unprepared reader, are increasing in the last sentence of the first chapter, and Griffiths even says that “Throw your watch into the sea.” The watch is a symbol here. At the end of the book, we understand that the timepiece that is said to be thrown into the sea is actually a mentality of domination and the idea of living a wrong time that enslaves us. Each chapter in the book depicts with examples that there is no single time.

Jay Griffiths explains that modern man has never understood or comprehended the “real” time(s) of the earth by saying “Modernity knows contraction and anxiety, not the watch”. The author thinks that even repairing things is a kind of protest against time in this fast life, and also explores possibilities outside the West’s perception of time. She is interested in how humanity perceives time and conveys to us the information she gained by traveling around the world. For example, in Burundi, time is described rather than counted. If the night is so dark that you cannot see someone’s face when you meet them, they call these nights as you-who-are-night. For the Inuit people of Baffin Island, the word Uvatiarru also means both “long in the past” and “in the future, long after”. For the Maoris, the past lies before them, so that, in the words of the Maori writer Witi Ihimaera, they “walk back into the future, give on to the past.”

The first chapter of the book deals with our present day, which has become unpleasant to be surrounded by wathces, and its depictions in various parts of the world. The second chapter on “speed” is followed by chapters on “the past” and the “carnivals and rhythms” of time. The next chapter on “time for women” is followed by chapters on “gender”, “power” and “money”. After the chapter on “progress”, the chapters on “future”, “nature” and “death” comes. The final chapter is about “wild,” liberated, unconstrained time and the possible insights of such a time.

The last and thirteenth chapter of Pip Pip: A Sideways Look at Time was written in one of the rare natural areas on earth, Alaska, that wild lands where a wild river flows, and that the tales told begin with the words “long ago, in the future”. This part titled “Wild Time,” represents the thirteenth hour, the unrecorded wild time, which is not time-bound. The author begins to describe the wild time with sundials: “For example, sundials encompassed and tamed only the day. In the time of these hours, there were no ‘clocks’ at night. As the shadow of the hour hand spread after twilight, time would blend into the shadows of the dark night and the wild time.”

The Geography of Time, Robert Levine, translation: Özgür Umut Hoşafçı, Maya Books, 2013.

Sub-title: On Culture’s Perception of Time. The Geography of Time and Pip Pip: A Sideways Look at Time complete each other since they deal with the similar issues. The chapters “A Brief History of Watch Time” and “Fast, Slow and the Quality of Life” are very interesting. The quotes at the beginning of the chapters in the book are also very good. Although the way societies perceive time is more involved, there is also information about clocks:

“It was just after the first mechanical timepieces began marking the hours that the word “speed” (originally spelled “spede”) first appeared in the English language. Not until the late seventeenth century did the word “punctual,” which formerly described a person who was a stickler for details of conduct, come to describe someone who arrived exactly at the appointed time. Only a century after that did the word “punctuality” first appear in the English language as it is used today.”

The Book of Time: The Secrets of Time, How it Works and How We Measure It?, Adam Hart-Davis, translation: Cem Duran, NTV Publications, 2013.

This is an excellent book. However, there is no such thing as NTV Publications anymore, the publishing house was closed in 2016. Luckily (although some had minor issues) they left some good books behind. In the Book of Time, which includes many photographs and drawings, almost every subject from philosophy to science, from anthropology to technology, from nature to calendars is mentioned. Of course, every watch enthusiast will slow down for a while in the 4th episode titled “Measuring Time”, because this episode describes the technological evolution of the watch. The pages about the first pocket and wrist watches and John Harrison are very good.

The Melody of Time, Pierre Cassou-Nogues, translation: Nazlı Ceyhan Sümter, Kolektif Book, 2016.

The Melody of Time is one of the best books I’ve ever read. Laziness, procrastination… in short, there are excellent essays on wasting time. In addition to the fact that almost all texts such as “Watching the Whirling Clock”, “The Melody of the Clock” and “The Circle of the Clocks” relate to each other. It is also nice to be mentioned the works of Oliver Sacks, Raymond Queneau, Guy de Maupassant, Charles Baudelaire, Raymond Carver and many more.

Time, Philip Turetzky, translation: Mustafa Çağlar Atmaca, Otonom Pub., 2015.

This book, compiling the history of the philosophy of time, examines its development in the European world of thought, from Ancient Greece to contemporary approaches. The work, which has an extremely simple name, is also modest but rich in content. While the first part of the book chronologically describes the theories of time developed in ancient and modern philosophy, from Aristotle to Nietzsche, the second part with a more flexible way focuses on only three philosophical approaches (represented by McTaggart and Mellor, Husserl and Heidegger and Bergson and Deleuze) in the 20th century. Reading philosophy books has always been difficult for me, but this book is different. For example, there is a quote from Omer Khayyam at the beginning of the “Time Mode and Existence” chapter:

“Olanların olacağı belliydi çoktan;

İyiyi kötüyü yazmış kaderi yazan;

Ta baştan gereği düşünülmüş her şeyin

Neden boşuna uğraşır, dertlenir insan?”

(trans: Sabahattin Eyüboğlu)

An Essay on Time, Norbert Elias, translation: Veysel Atayman, Ayrıntı Pub., 2000.

Sociologist Norbert Elias begins his book’s preface by referring St. Augustine: “An old sage said that ‘If no one asks me, I know what time is. If I wish to explain it to him who asks, I do not know.’”

I think that if there was a “Preface Anthology”, 43-page preface of this book would been definitely included in the anthology. Elias’s perspective is of the kind that compiles the complicated topics:

“Watches are the leading time representation mechanisms in developed societies. However, the mechanism called watch is not time itself. Although time has an instrumental character, this character of it appears in a unique and completely different way. When we try to examine the relationship between watch mechanisms and time, an interesting question arises: What kind of relationship is there between the physical event flow created by a time determinant, such as a clockwork, and the social function of the same device as a time notifier? The device, as a time determinant, is a tool that carries a notification to the person who wants to know the time, just as newsprint and the printed texts on it represent the physical means that carry news and information to the reader. Whether this tool is a watch or the Sun around which the Earth revolves, time determination processes are always carried out through the flow of events (movement of the hour-minute hand, sunrise-sunset) that can be perceived by our senses. This principle does not change when it comes to a written or printed calendar. The calendar performs the same function by creating the impression of time flow for us. However, whether it be the moving indicators of the clock, the Sun moving on the horizon, or the consecutive pages of the calendar; in order for these physical flows to serve to determine time, they must also have the character of dynamic social symbols and be embedded in the communication cycle of human society, that is, on the social plane, both as information transmitters and as regulatory symbols. Regardless of their source and characteristics, the tools that serve to determine the time are always message sources that only appeal to people without exception. Even if the mechanisms called watches are designed by humans, they represent dynamic events, that is, a physical relationship. However, they are instruments of physical origin that were placed within the human’s world of symbols and the social world with a certain way such as the changing positions of the hour and minute hands.”

Living the Time, Jean Chesneaux, trans: Münir Cerit, Ayrıntı Publications, 2006.

As it can be understood from the subtitle of the book “Past, Present, Future: An Essay on Political Dialogue”; history, philosophy and politics are the main themes of the work. “A Political Time Culture” chapter is eye-opening but especially the “Little Library of Time” chapter is a treasure in my opinion. I would very much like the books mentioned here to be fully translated into Turkish.

The Time Pyramids, Remo Bodei, translation: Durdu Kundakçı, Dost Bookstore Pub., 2010.

The Time Pyramids is a magnificent work. The subtitle of the book, “The History and Theory of Déjà-vu Emotion” may only partially explain my surprise. The book contains poems and impressive reviews. On the one hand, it is very serious because it is comprehensive research, and on the other hand, it is an interesting experience to read romantic sentences. The only downside to The Time Pyramids is that the footnotes are printed in the smallest possible font.

Eastern Man and Time & Human Law and Laws of Nature, Joseph Needham, trans. Nejdet Özberk, İz Publishing, 2000.

A lifetime of 94 years devoted to the history and philosophy of Chinese science can only superficially describe Joseph Needham. As an important figure who rewrote the history of science, Needham builds bridges between East (China) and West in this book (two books actually) and reassesses the roles of civilizations with fairness in the view of time and history.

A Brief History of the Philosophy of Time, Adrian Bardon, trans. Özgür Yalçın, Isbank Culture Publications., 2018.

The title of the book also summarizes its main topic. The bibliography of A Brief History of the Philosophy of Time is very good. An amazing library can be created only from the works in this bibliography. The author is an academician who thinks that philosophy can achieve success by working with the applied sciences. As we read the book, we understand that the research on time is also the best example of this cooperation.

The Order of Time, Carlo Rovelli, translation: Tolga Esmer, Tellekt, 2020.

Although the author has a style of expression that I find a bit sharp in general, it was very nice to read the “The Scent of the Madeleine Cake” chapter. My only complaint is that the notes at the end of the book are too small for the human eye to read. Maybe it’s not right to say a complaint, let’s say a reproach on behalf of readers with glasses like me. Otherwise, there is a lot of effort in the book.

The Concept of Time, translated by Saffet Babür, İmge Publishing House, 1996.

The Concept of Time book contains three important texts titled The Physics by Aristotle, Confessions by Augustine, and The Concept of Time by Heidegger. There is the original text on the left pages of the book, and the Turkish translation on the right pages. The work that should be read right after The Concept of Time is Martin Heidegger’s work called Being and Time (trans: K. H. Ökten, Agora Library, 2011) based on these texts.

P World Art, Time and Art special issue, Winter 2003.

Years passed, but P World Art (1996-2010) magazine could not be replaced. The magazine was, in which experts in the field elaborated on a particular subject in each issue, one of the keystones of our publishing world. The “Time and Art” special issue of the magazine, which makes an important contribution to our cultural world, is also extremely beautiful. The fact that it remains “fresh” despite the passing years shows that the magazine itself has become a work of art.

Time and Space, Mary Gribbin – John Gribbin, translation: Gürsel Tanrıöver, TÜBİTAK, 2005.

Although it has an awful cover and some of the information is now outdated (it came out in English in the 1990s), Time & Space is still a good reference. Moreover, it has many drawings and photographs. In the book, in which the philosophy of time is explained in two pages (!), there are also very interesting topics such as biotime and biospace. After all, it is a must-have book for any clock enthusiast, even just for the detailed and annotated photograph of John Harrison’s H-1 clock. (Unfortunately, there is no such detailed photograph even in the Longitude book that I introduced in the previous article.)

Note: The next article is on time travel and time machines.