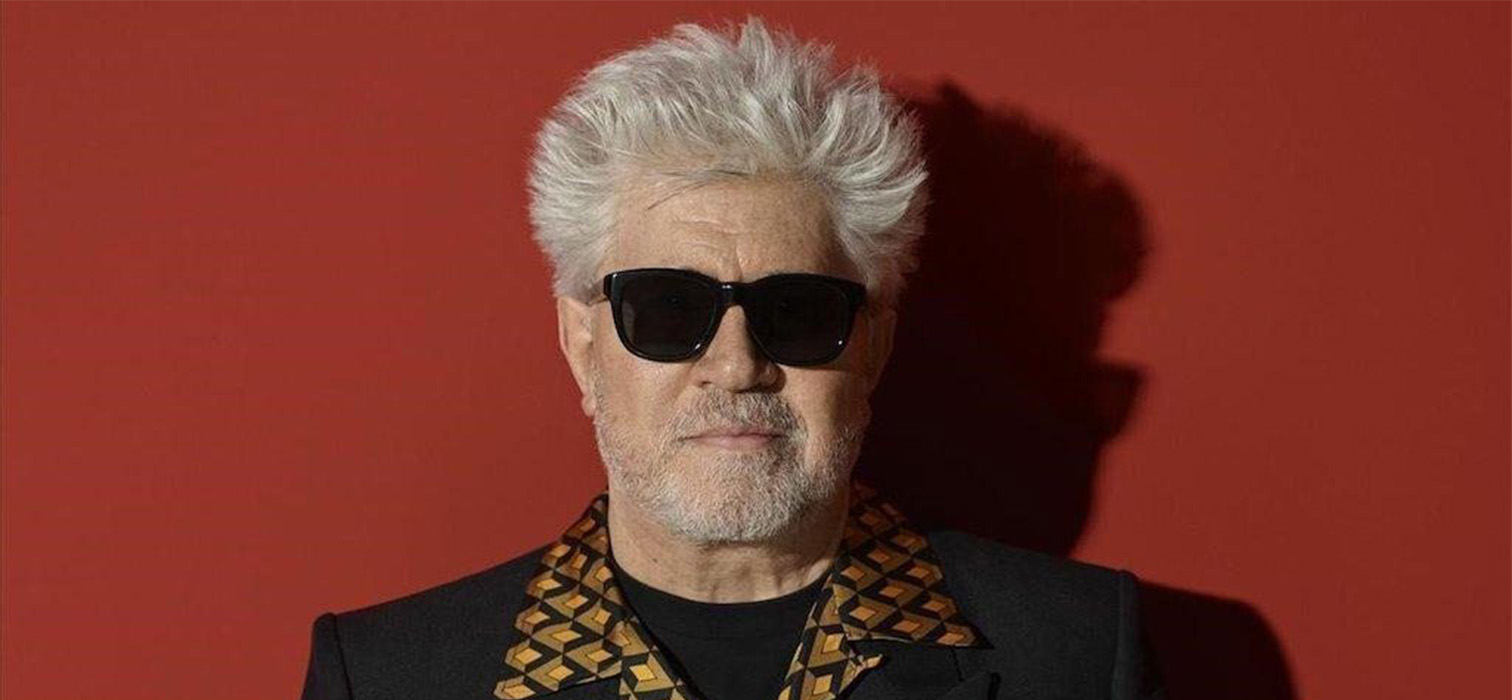

Pedro Almodóvar: The Master of Finding Solace in Fiction

Pedro Almodóvar, the cinematic maestro, has captivated audiences with his bold storytelling, unforgettable characters, and boundless passion for film.

At just eight years old, Almodóvar experienced a pivotal moment that would shape his artistic vision. His family moved from La Mancha to a modest town in Extremadura, with its humble adobe houses and slate-paved streets. His mother, Francisca Caballero, supported the family by reading and writing letters for their illiterate neighbors.

One day, young Pedro noticed something curious. While reading a letter aloud, his mother embellished its content, adding lines like, “I hope my grandmother is well; there’s not a day that goes by that I don’t think of you all.” The words, however, weren’t in the original letter. Pedro was alarmed by this improvisation and questioned her when they got home. Her reply was simple yet profound: “Didn’t you see how happy they were?” This moment stayed with him, planting the seeds of a powerful realization: fiction has the extraordinary ability to make life more bearable. It helps us navigate reality with hope and imagination.

Almodóvar has since become a master of weaving truth, lies, and imagination into mesmerizing stories that pulse with raw emotion. His films are a whirlwind of love, pain, and humanity—extraordinary tales that make us laugh, cry, and ultimately feel more alive.

Pedro Almodóvar‘s illustrious career spans an incredible 42 films as a screenwriter and 40 as a director, each a testament to his unparalleled love for cinema. His debut feature, Pepi, Luci, Bom and the Other Girls (1980), set the stage for a career bursting with color, wit, and emotional depth. From Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown (1988), which swept five Goya Awards, to All About My Mother (1999), a heartfelt dedication to women and mothers, Almodóvar’s films are milestones of cinematic brilliance. The accolades keep rolling: Talk to Her (2002) earned 32 awards, The Skin I Live In (2011) won a BAFTA, and Pain and Glory (2019)—infused with autobiographical elements—brought the world closer to understanding the man behind the lens. His filmography is so compelling that skipping even one feels like a disservice to the magic of cinema.

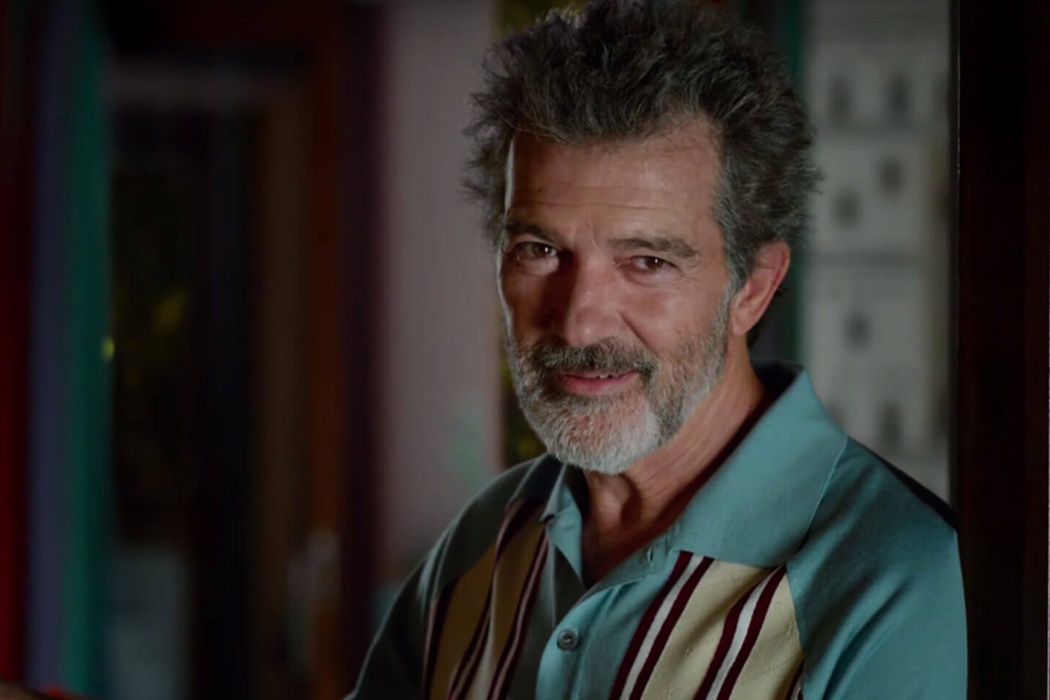

In Pain and Glory, Almodóvar’s protagonist, Salvador Mallo—a melancholic filmmaker played by Antonio Banderas—delivers a poignant line: “If I don’t make movies, my life has no meaning.” Though Almodóvar insists Mallo isn’t his direct reflection, elements of the film suggest otherwise. From Banderas wearing Almodóvar’s own clothes to scenes shot in the director’s Madrid apartment, it’s clear that Mallo’s struggles echo Almodóvar’s deep connection to his craft.

In a candid interview, Almodóvar once revealed his all-consuming relationship with storytelling: “The need to tell stories is an addiction; I cling to it. But my relationship with film is becoming more and more tense, more problematic, because that question is always lurking: When will my time be up? Will it be the last movie I make? Maybe that’s why I haven’t developed other aspects of my life. Cinema is the only thing that makes me feel whole.”

Despite these doubts, his creativity shows no signs of fading. Since expressing these sentiments, Almodóvar has gifted audiences with five more films, including shorts, proving once again that his cinematic voice is as vital as ever.

Born on September 25, 1949, in the quiet town of Calzada de Calatrava in Castile-La Mancha, Spain, Pedro Almodóvar’s childhood seemed destined for a very different path. Sent to a religious boarding school in Cáceres, his parents dreamed he would become a priest. But Almodóvar found his true calling not in the chapel, but in the local movie theater. “The cinema was my real education. It taught me much more than I could have learned from a priest,” he later reflected. In 1967, Almodóvar defied his parents and moved to Madrid, drawn by the city’s vibrancy. By 1975, with the death of dictator Francisco Franco, a new era began. The La Movida Madrileña cultural movement swept through Madrid, bringing an explosion of artistic freedom, rebellion, and creativity. For Almodóvar, it was a transformative moment. “Franco had to die for me to live,” he said, as Madrid was electrified by British punk, glam rock, the American New Wave, and the lingering echoes of the 1960s sexual revolution.

After The Substance: Films To Watch That Broke the Mold

No Winter This Year: Summer 2024 Concerts and Festivals

During this period, Almodóvar embodied the energy of La Movida. By day, he worked a steady job at Telefónica, Spain’s telephone company, a position he held for 12 years. But by night, he was a man of many passions: singing in a band, performing in theater, penning articles and stories for magazines, and immersing himself in the city’s burgeoning alternative scene. His nights were fueled by an insatiable appetite for the creativity buzzing through Madrid’s clubs, bars, and underground venues.

A pivotal moment came when Almodóvar used his first paycheck from Telefónica to buy a Super-8 camera. With it, he began shooting silent sex comedies, unapologetically provocative and filled with kitsch. These films, projected on nightclub walls, became his first foray into storytelling through cinema.

In 1980, Almodóvar made his feature-length debut with Pepi, Luci, Bom and the Other Girls, a film that boldly challenged Spain’s lingering taboos. While critics were dismissive when it premiered at the San Sebastián International Film Festival, the film gained a cult following and established Almodóvar as a daring new voice in Spanish cinema. For the next eight years, he continued making films annually, sharpening his style and pushing boundaries. By 1988, everything changed. Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown brought him international acclaim and an Oscar nomination for Best Foreign Language Film. The newfound success prompted a memorable call from his mother: “This is probably a good time for you to call Telefónica and ask for your job back.” Almodóvar, of course, had found his true career—and the world of cinema would never be the same.

Almodóvar’s relationship with his parents, particularly his mother, remains a poignant thread running through his life and work. Despite the deeply personal melodramas he brought to the screen—fraught with sin, tears, and redemption—he never truly crossed a certain threshold in real life. “I was never the child they wanted me to be. They really loved me, but I always felt this,” he once revealed. Born into the conservative heart of La Mancha, Almodóvar described himself as a 21st-century child in a 19th-century world. His parents envisioned a life of stability for him: staying in the village, working in the bank, and settling down. “They even got me a job in the bank,” he recounted. “I hated town life… Everything was inward, looking at each other. The only thing they worried about was what the neighbors would do or think. It was hell for me. All I wanted was to get out of there, to escape.”

Thankfully, escape he did. Madrid welcomed him with open arms, and he began crafting one masterpiece after another with unrelenting enthusiasm and creativity. Without that escape, the world would have been deprived of Almodóvar’s cinematic marvels—films that explore life’s raw, familiar dimensions, requiring a rare kind of bravery to reveal.

Almodóvar’s films are nothing short of visual and emotional feasts. Every frame is a testament to his meticulous attention to detail, from evocative set designs to carefully chosen costumes that mirror the emotional landscapes of his characters. As he unpacks themes like identity, sexuality, and family dynamics, he introduces us to strong, multifaceted female characters whose struggles and resilience command both empathy and admiration. Blending melodrama, comedy, and suspense with effortless sophistication, Almodóvar creates complex plots brimming with twists and reversals. His characters, with their profound flaws and emotional richness, evoke a sense of deep connection—an undeniable reflection of his own observations and experiences. Through his rich narratives and audacious storytelling, Almodóvar celebrates life by embracing its complexity and finding truth within fiction. His films are not merely stories but vivid explorations of humanity, where every moment pulses with the undeniable vitality of imagination.

There are, of course, the actors he has included in his films with a fidelity that one would not expect from his mad pen: The venerable Antonio Banderas; the marvelous Penélope Cruz; Carmen Maura, who appeared in early films such as What Have I Done to Deserve This? and Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown; Rossy de Palma, unforgettable for her distinctive look; and the talented Julieta Serrano.

But where does his latest Golden Lion-winning film, The Room Next Door, fall in a filmography that smells of Spain and the Mediterranean? First of all, it is the director’s first feature film entirely in English, having so far established a relationship with Hollywood based on mutual respect and cautious distance. Always keen to maintain his independence, Almodóvar never volunteered to enter the Hollywood system—in fact, he turned down an offer to direct Brokeback Mountain for fear of not being able to work in complete freedom. This is because one of the elements that make his films unique is that they emphasize cultural elements. Hollywood has its own cultural codes.

Therefore, The Room Next Door, starring Hollywood stars Julianne Moore and Tilda Swinton, adapted from Sigrid Nunez’s book What Are You Going Through, about the emotional journey of two friends who reunite after years under the shadow of a fatal illness, and shot in New York for a short part, but mainly in Spain, received conflicting reviews.

Some praised the strong performances of the actors and said Almodóvar blended European elegance with American spirit. Others criticized it as didactic. Others called it slow, colorless, bland—adjectives that Almodóvar’s films should never be compared to.

But even if The Room Next Door is a bit offside in the movie universe, we mortals who adore the director can take solace in the thought that Almodóvar’s time will never end, as long as his passion for storytelling never ends.