French Elegance Shines in Hong Kong: Fashion and Jewelry from 1770-1910

The Hong Kong Palace Museum unveils a dazzling showcase of French fashion and jewelry, highlighting their influence on social status and aesthetics in Asia.

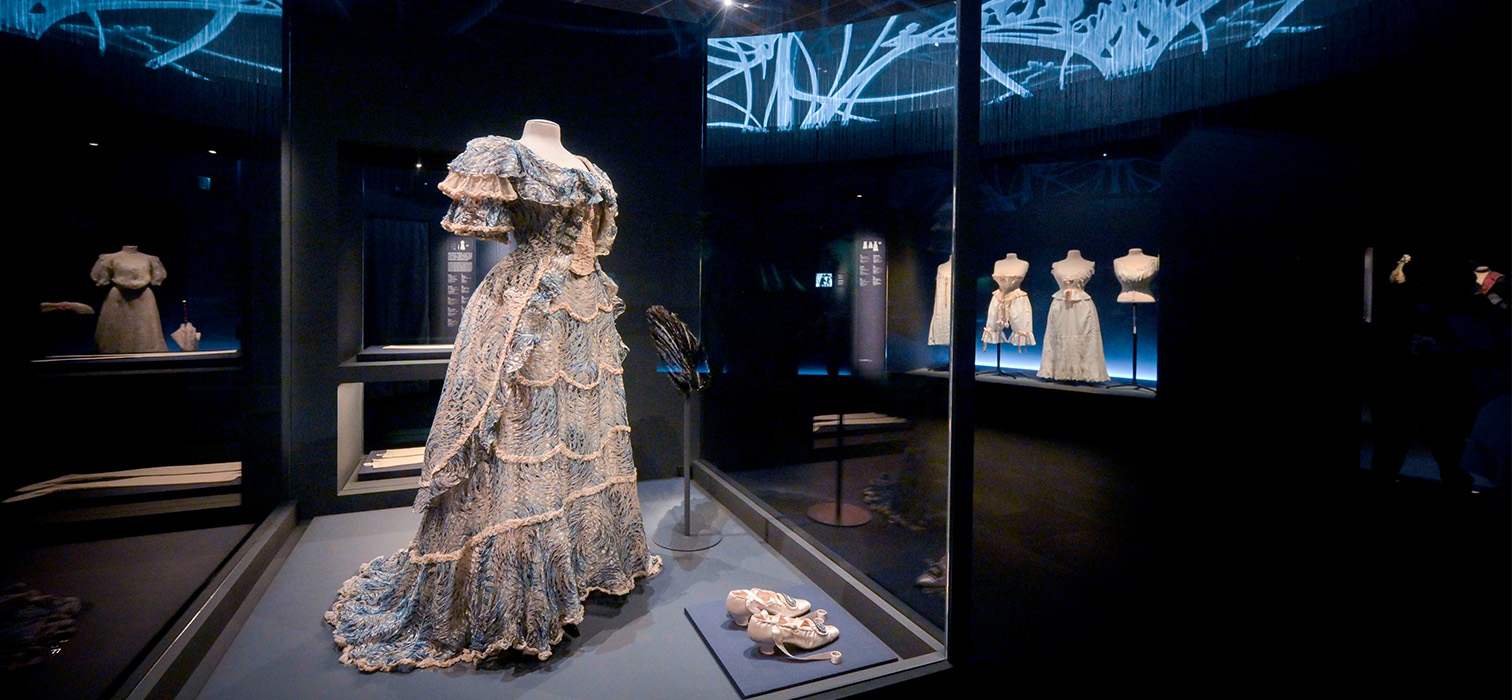

Co-organized by Paris’s Musée des Arts Décoratifs and the Hong Kong Palace Museum, the exhibition, titled “The Adorned Body: French Fashion and Jewellery 1770-1910,” marks the Musée’s first-ever display in Asia. Featuring the largest collection of historical French fashion, it celebrates 60 years of diplomatic relations between China and France. As one of four major exhibitions in the West Kowloon Cultural District in 2024, it is housed in Gallery 9 of the museum and runs until October 14.

The exhibition showcases nearly 400 exquisite garments from the late 18th to early 20th century, illustrating how jewelry and accessories could transform the body and signify social standing. It also delves into captivating narratives about the evolution of French fashion and the cultural exchanges that influenced its development.

Divided into five sections, the exhibition explores Court Splendor (1770-1790), Sense and Sensibility (1810-1830), Tradition and Innovation (1850-1860), The Birth of Luxury (1880), and the Belle Époque (1890-1910).

Palace Splendor (1770-1790)

The exhibition opens with Palace Splendor, presenting the opulent dresses and suits worn at the French court in the 18th century, alongside dazzling jewelry and rare accessories.

During this period, the corset and pannier, known as “stays,” dramatically transformed the silhouettes of women at court. French fashion dominated Europe, with French-made goods renowned for their elegance and superior quality. The textile industry, especially silk production in Lyon, thrived as the demand for luxurious garments grew among the elite. Both men and women used fashion to display their social rank, with men’s court attire featuring intricate embroidery crafted by expert designers. Women’s fashion of the era set trends with pastel hues, embellished with lace, ribbons, and even floral accents.

In 1770, Marie Antoinette (1755-1793), archduchess of Austria, married the Dauphin, later Louis XVI (1754-1793). As queen of France, she became a fashion icon, shaping the court’s style and influencing many of the trends featured in this section. One highlight is an 18th-century inner coat worn by an aristocratic man, which reveals the global connections between China and France. The coat is crafted from French silk, inspired by the luxurious fabrics produced in China. Other pieces in the exhibition also showcase designs influenced by Indian, Japanese, and British styles, reflecting the era’s vibrant cultural exchanges.

Sense and Sensibility (1810-1830)

The French Revolution, beginning in 1789, brought about a minimalist aesthetic, in stark contrast to the extravagance of the former court. However, when Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821) became emperor, he reintroduced ornate court attire, including the habit à la française (the precursor to the modern three-piece suit), helping to revive the struggling textile industry. His wife, Empress Joséphine (1763-1814), favored the neoclassical high-waisted dress, which became a defining trend in women’s fashion in the early 19th century.

After Napoleon’s initial fall in 1814, the Bourbon monarchy was restored with Louis XVIII (1755-1824) as king. By the mid-19th century, the rigid bell-shaped crinoline, or hoop skirt, emerged as one of the most dramatic fashion trends, gaining popularity throughout France and Europe. By 1865-1866, the crinoline reached its peak size, making it difficult for women to pass through narrow doorways.

The corset, which cinched the waist and made breathing difficult, became a symbol of both the pleasure and pain associated with beauty. When women felt faint from tight corsets, they would sniff a vinaigrette—a small container with a sponge soaked in a strong substance—to revive themselves. This highlights how fashion often gave rise to new accessories. The corset reached its final peak in popularity in the early 1900s, before the bra was introduced around 1905. A revolutionary garment, the tailored suit was designed for the modern woman’s active lifestyle. During the Bourbon Restoration (1814-1830), romanticism flourished, with puffed sleeves, corseted waists, and dramatic crinoline skirts defining the fashionable female silhouette of the time.

Tradition and Innovation (1850-1860)

The 1850s were a decade of economic prosperity and splendor. During the Second Empire of Napoleon III (1852-1870), grand celebrations, including the emperor’s wedding in 1853, dazzled with traditional courtly magnificence. Paris, the “City of Light,” buzzed with a festive atmosphere as shops and shopping arcades made fashionable clothing and accessories more accessible to the growing middle class.

Women’s clothing became more vibrant with the invention of synthetic dyes, while the steel hoop crinoline lightened the weight of skirts, making them easier to wear. The crinoline craze, which spread from France to Britain and across Europe, was largely inspired by Empress Eugénie (1826-1920), whose fashion influence boosted French manufacturing and international trade in luxury goods.

The Birth of Luxury (1880)

As France’s foreign trade surged between 1860 and 1880, the luxury goods market flourished, driven by the high demand from affluent women. By the late 19th century, social etiquette required women to change dresses and accessories multiple times a day for different occasions. The crinoline, worn beneath the skirt to shape the silhouette, remained essential in the 1880s.

The most sought-after dresses were crafted by Charles Frederick Worth (1825-1895), often called the “father of haute couture.” His devoted clientele included royalty and socialites from across Europe and the Atlantic. Worth was among the first to use live models, pioneering the concept of the “fashion show,” and he was also the first designer to sew branded labels into his creations—innovations that continue to influence the fashion world today.

Belle Époque (1890-1910)

The turn of the century saw a rapid acceleration in life with the expansion of railroads, the invention of automobiles and airplanes, and the social transformations brought by technologies like radio. During this vibrant era, Parisian operas, theaters, café concerts, and even the streets were illuminated, showcasing the spectacular Art Nouveau designs that defined the city’s aesthetic.

Fashion-forward women embraced flowing silk dresses and nature-inspired jewelry, highlighting their curvaceous silhouettes. France became a hub for artists, musicians, dancers, and writers from across Europe and the world, who sought to create new forms of expression. Traditions began to relax, with men adopting the three-piece suit for daytime and the tuxedo for evening wear. As women’s social roles evolved, so did their wardrobes—modern women opted for blouses, skirts, and jackets that reflected their active, independent lifestyles.