Calumeno Mausoleum: Design Facing Death

Death is a topic most people prefer not to dwell on. Yet, when it comes to cemetery design, it offers an unexpectedly compelling field of exploration for architects. One name behind a singular architectural experience in Turkey is Evren Öztürk, who designed the Calumeno Mausoleum.

This design presents quite an unusual perspective architecturally. Let me begin by asking: how did this project come to you?

The project originated with businessman and collector Orlando Calumeno, with whom I’ve collaborated for many years. Mr. Orlando owns an extensive collection of items from the Late Ottoman and Early Republican periods —thousands of postcards, documents, and everyday objects. In the past, when he needed a space to display and partially sell this collection, we designed 3×3 meter shops in the Hak Passage in Nişantaşı. The mutual trust built through those projects eventually led to a much more personal and meaningful commission: the Calumeno Family Mausoleum.

Is there a reason you emphasize the 3×3-meter dimension?

Yes, because the mausoleum we’re discussing has the exact same floor area. At the time I was designing those tiny shops, I never imagined I’d be applying the same spatial constraints to a mausoleum someday. After that early collaboration, we completed several projects for Mr. Orlando. Then one day, he approached me and said, “We’re going to do something interesting.” He asked me to design a mausoleum for himself and his family.

Is this concept similar to a family grave in Islamic tradition?

Yes, quite similar. It was conceived as a memorial tomb for five individuals. In Islamic culture, its counterpart would be a türbe (mausoleum). It’s a place where coffins are laid to rest and visitors can come to pray.

As an architect, had you encountered such a project before? Are these types of commissions common in architectural practice?

To be honest, I can only recall one or two cemetery-related design competitions. One example was the Istanbul Cemeteries Design Competition organized by the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality, which focused primarily on Muslim cemeteries. Those competitions produced some really high-quality proposals. However, I had never encountered a project or competition specifically aimed at designing a Catholic mausoleum. These structures are quite rare in Turkey. Due to their cultural and typological uniqueness, such projects are not commonly found in architectural practice. That’s precisely why this project offered such an intriguing experience for me.

Is monumental architecture something that’s typically addressed in architectural education?

Not usually. It’s not a core subject, nor is it commonly offered as an elective. However, it can appear as a design challenge in studio projects, depending on the instructor’s initiative. For instance, a cemetery or monument might be assigned based on the semester’s theme. Personally, I didn’t encounter any projects directly related to cemeteries during my education. That said, cemeteries, like any other structure, can be approached through architectural design.

I’m curious—how did the brief for a structure like this come to you? How did the design process take shape?

Before diving into the process itself, it’s helpful to first understand the needs a mausoleum must meet. At the outset of the project, Mr. Orlando entrusted me with the task of designing a modern mausoleum that would reinterpret traditional elements. Within that framework, I had full creative freedom to shape the direction of the design.

Functionally, there were several core requirements. Mausoleums are essentially small chapels. They typically include a space at ground level for visitors to pay their respects, and a lower level where the coffins are stored. There were also specific dimensional constraints dictated by the Feriköy Latin Catholic Cemetery.

From a technical standpoint, natural ventilation was especially critical. In Latin Catholic mausoleums, the deceased are not usually buried directly in the ground. Instead, a sealed zinc coffin is placed inside a wooden one for preservation. This makes air circulation and maintaining indoor air quality essential. In short, there was a very clear and specific technical brief. All other architectural decisions were left to my discretion, which made the project both exciting and highly challenging.

This is a difficult topic for many people to even contemplate. As an architect, how did you feel when faced with such a project?

Although the subject is directly tied to death, my initial reaction as an architect was one of excitement. This is a rarely explored area in architectural practice and requires a degree of courage to approach. Meeting a client willing to engage with such an under-addressed topic—and someone capable of discussing death and ritual from an architectural perspective—truly impressed me. The fact that someone entrusted an architect with such a deeply personal and sensitive issue, and approached it with such thoughtfulness, was a strong motivating factor as I began the project.

How does your architectural method come into play when you’re working on a subject you’ve never dealt with before?

In fact, in most projects, architects are not expected to know everything from the start. Our job is to design a process by asking the right questions about unfamiliar subjects, collaborating with the right people, and carefully analyzing needs. I adopted the same approach for this project. I didn’t begin with deep knowledge of the topic, but through discussions with historian Rinaldo Marmara—who has studied the cemetery—Mr. Orlando, cemetery officials, and various suppliers, we gradually built an understanding of the spatial and ritual requirements. So the issue isn’t about possessing complete knowledge from the outset, but about managing a process that generates that knowledge.

Were there any religious rules or restrictions that influenced the project, given its spiritual context?

Naturally, the family held religious beliefs, and we approached the project with sensitivity and respect. However, there were no strict religious prohibitions or rigid constraints that dictated the design. The primary limitations were technical in nature. For instance, the structure needed to fit within a 3×3-meter plot. From there, we posed questions such as: How much vertical space could we create within these dimensions? How deeply could we excavate? How could we achieve spatial depth? In this sense, it wasn’t belief systems that imposed boundaries, but rather the physical and technical parameters of the site that shaped the project.

What were your primary criteria in the design?

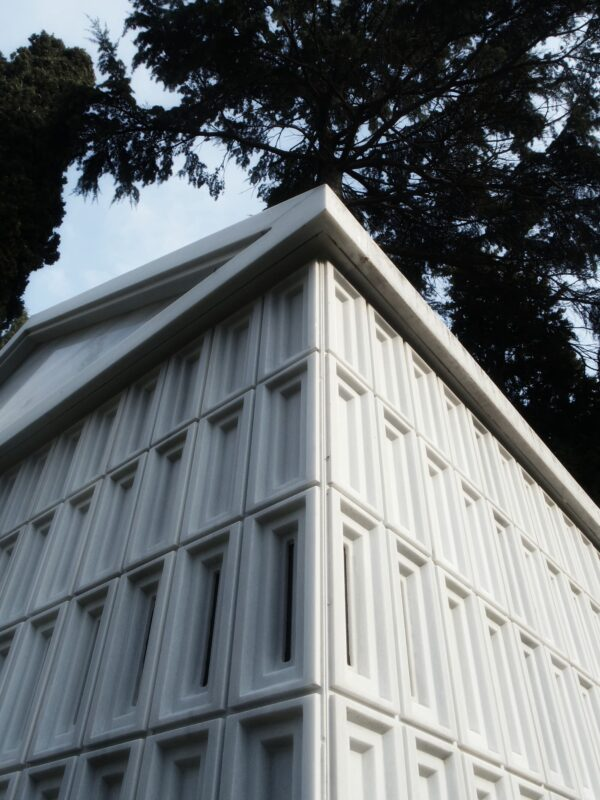

At the heart of the design process was the architectural fabric of the Feriköy Latin Catholic Cemetery, the site of the mausoleum. This cemetery is home to many distinctive mausoleums belonging to Istanbul’s historic Levantine families. With their triangular pediments, pitched roofs, and prismatic volumes—each conforming to particular proportions—these existing structures served as significant reference points. Notable examples include the mausoleums of the Rossi, Scotto, and Castelli families. Drawing from these precedents, we sought to maintain formal continuity while respecting the cemetery’s overall atmosphere. Thus, preserving the existing architectural fabric and introducing a contemporary interpretation within that continuity became one of the most essential design principles.

How did you manage to preserve the fabric of the cemetery despite using modern materials and techniques?

The design is rooted in two fundamental forms drawn from the cemetery’s existing architectural language: the triangular pediment and the prismatic mass beneath it. This compositional style is quite common in the cemetery, and we aimed to maintain this formal continuity. We approached material selection with the same level of sensitivity.

We deliberately chose not to deviate from Marmara marble, which is widely used throughout the cemetery. We understand how this stone ages—how it darkens, how moss settles on its surface. We wanted a material that would show the same signs of aging even after a hundred years, helping the structure remain visually in harmony with its surroundings. Ritual elements were also thoughtfully placed: planters for flowers at the entrance, candle holders inside, and, of course, a cross.

When was the last time a mausoleum was built in this cemetery?

The Calumeno Mausoleum is the first original mausoleum to be designed and constructed from scratch in this cemetery after the Republican era, nearly a century later.

So where does the project diverge from tradition?

Once we had established a general idea of how the structure would be shaped, we began to focus on the details that would give the mausoleum its distinctive character. The most significant of these was the use of cassette panels on the exterior. These components are not merely decorative surface textures—they serve as architectural building blocks that define the structure’s identity.

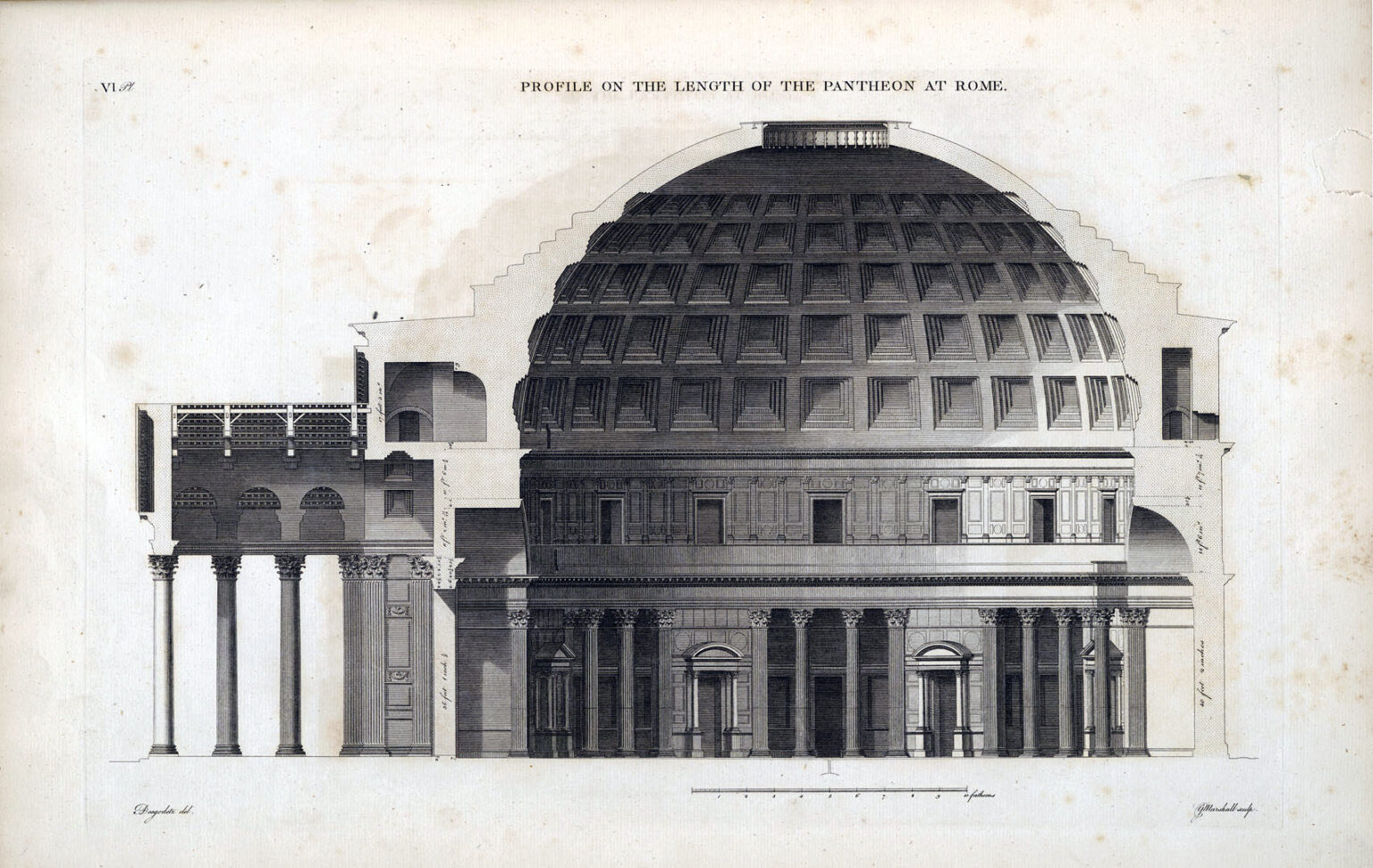

With these cassettes, we aimed to make a direct reference to the family’s Italian heritage. Our inspiration came from the coffered ceiling system (cassette structure) inside the dome of the Pantheon in Rome. In that iconic space, the cassettes are used not only to reduce structural weight but also to create depth and a dynamic interplay of light and shadow across the surface. In a similar spirit, we designed our cassette system to evoke a rhythmic play of light on the façade through these layered, stepped surfaces. Over time, this coffering developed into a defining and expressive architectural language—one that became a unique hallmark of the mausoleum.

How did concepts such as horizontality and verticality shape the architectural design?

In this project, the concept of horizontality gained meaning through its association with the fan element, symbolizing the transient, earthly dimension of life. Verticality, on the other hand, drew its significance from its connection to both the subterranean and the celestial—pointing simultaneously to the underworld and the heavens. Put simply, the horizontal represents this world and its impermanence, while the vertical stands for the afterlife and the spiritual realm.

The vertical alignment of the cassette panels on the exterior façade enhanced the perceived height of the mausoleum, further emphasizing the structure’s vertical axis. This upward movement reinforced the symbolic power of the design. In the same vein, the skylight—an opening that introduces natural light from above—played a crucial role in strengthening this vertical relationship. By carefully directing the light that enters through this aperture, we aimed to create an interior atmosphere that evokes a sense of the infinite. In both symbolic and spatial terms, the vertical axis became one of the building’s fundamental layers of meaning.

How was the cross shape incorporated into the mausoleum?

After designing the cassette façade, we conceived the idea of carving a slit at the deepest point of these cassettes to admit light. This opening projects a cross-shaped beam into the interior. Thus, visitors entering the mausoleum are met by a cross formed by light—a quiet but powerful gesture. This decision naturally echoes Tadao Ando’s Church of the Light, one of the most iconic examples of architecture shaped by the interplay of light and concrete. Acknowledging this reference, we cast the cross shape directly into the concrete formwork, making it both a symbolic and structural element of the design.

Was there any feature in this project that had never been done before?

Yes, the glass flooring was particularly unprecedented. In traditional Catholic mausoleums, the floor resembles a chapel, and the cover can be opened to access the chamber below. However, these lower spaces often feel dark, enclosed, and over time become places people prefer to avoid. We wanted to reverse that perception—to create a space that invites descent, both spatially and emotionally. We designed a comfortable staircase, ensured natural light would enter from above, and, most importantly, implemented a glass floor to visually connect the upper and lower spaces.

It was a bold material choice, but after extensive discussion with the client and contractor, we made it a reality. One of the advantages of the glass floor is that it allows the coffin to be seen clearly while framing it together with the descending light. Visitors are thus offered a powerful and emotional visual connection. We used laminated tempered glass for safety and optimal light transmission.

What role did craftsmanship play in the project?

Looking at the historical mausoleums in Feriköy Latin Catholic Cemetery, one finds many examples of detailed craftsmanship—frescoes, statues, column capitals. One of the central questions we asked was: How can we reinterpret this tradition today, and with what tools?

Our answer was to blend traditional craftsmanship with contemporary fabrication methods. The cassette panels, made from Marmara marble, were carved layer by layer using water-jet CNC technology. But the process didn’t end with digital cutting—the inner surfaces of each cassette were then hand-sanded and finished. So, a process that began digitally was ultimately completed by human hands.

Moreover, the internal geometry of these cassettes served as the basis for a typographic identity. The areas created by the cassettes guided the design of all inscriptions: the family name on the triangular pediment, the tombstone engravings, and the interior marble texts—all were developed using a font specifically designed for this structure. Craftsmanship thus extended beyond surface detail to define the graphic and symbolic language of the building.

Another significant application of craft is the raw concrete dome system inside the mausoleum. We combined raw concrete surfaces—chosen for the interior walls and ceiling—with skylight elements, all shaped using custom formwork. Through this, we aimed to develop a fresh interpretation of how craftsmanship can be expressed in concrete.

Was there a specific example that influenced you in exploring such detailed workmanship?

Yes, years ago I came across a year-end exhibition at Chiang Mai University in Thailand, hosted by the Faculty of Art and Technology. A student had created dozens of versions of a Buddha statue—some sliced into layers, others perforated. All were made using a 3D printer. By repeatedly reinterpreting the same sacred form through technology, the student had pushed the visual boundaries of the Buddha’s image to the point where its metaphorical meaning nearly vanished. In a country where Buddha symbols are omnipresent, this was a strikingly avant-garde approach.

It made me ask: How transformable is a material within its own limits? That question stayed with me throughout the design of the marble coffins in the Calumeno Mausoleum. It led to an experimental process in both how marble is worked and how marble can be made to feel.

The coffin itself was specially designed for this project, wasn’t it?

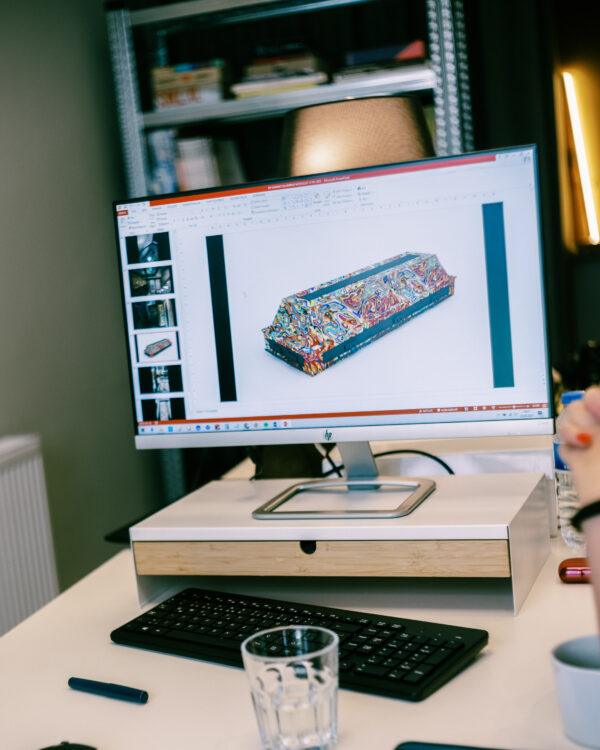

Yes, the coffin was created by painter Memduh Kuzay. He incorporated symbols of Catholicism and the family, along with graphic elements and colors reminiscent of antiquity. He prepared the sketches, and we had the opportunity to collaborate closely on the design. It was a fascinating experience to engage with such a deeply personal object.

Is it common to design the coffin when working on a mausoleum?

Not at all. Typically, the coffin is not prepared unless there’s an imminent funeral. This was purely a personal choice.

That’s unusual—how did the conversation around it evolve?

Yes, it was quite unusual. Memduh Bey’s studio is in Karakoyunlu village in Kayseri. The coffin was first shipped there, and he worked on it in his workshop. Once it was completed, it was carefully stored and later sent back to Istanbul. One day, Orlando Bey’s assistant, Sevil Hanım, called and said, “Evren Bey, I don’t know how to put this, but Orlando Bey’s coffin is ready.” Hearing that a coffin is “ready” was a surreal moment. (Laughs)

Have you ever thought about your own death?

To be honest, no. I’ve never thought about it in the sense of planning for my own death. Perhaps not every architect approaches such a project this way, but I tried to maintain a certain distance—more like a doctor’s clinical detachment. Throughout the process, I focused on meaningful design relationships and technical requirements. As an architect, I believe even structures associated with death can and should be thoughtfully designed.

A mausoleum is often expected to feel dark and somber. Yet this space feels surprisingly airy. Was that intentional?

Yes, it was a deliberate choice. We wanted the mausoleum to feel more like a chapel or a small museum. Instead of the enclosed, shadowy atmosphere often associated with traditional mausoleums, we aimed to create a more open and contemporary space. Our goal was to allow people to engage not only with the tomb but with the architecture itself—and to feel the presence of light moving between inside and out. Spatial openness was an essential design consideration from the beginning.

Has your architectural approach changed after this project?

Absolutely. This was a rare and extraordinary experience. While I’m interested in all aspects of design, this project deepened my belief that even the most sensitive and difficult subjects can be addressed through thoughtful design. It has inspired me to take even greater care in all future work.

Has it opened new professional doors for you?

In architecture, you don’t always choose your direction —your path is partly shaped by the projects you’re offered, how they’re received, and the network of clients that grows around them. Whether or not this project opens up a new area of focus, time will tell…

Who Is Evren Öztürk?

Born in Istanbul in 1978, Evren Öztürk graduated from Saint-Benoît French High School before earning his architecture degree from Istanbul Technical University in 2004. He began his professional career at Boran Ekinci Architecture and worked there for eight years. In 2015, he co-founded the design office KO-Arch with architect Ceren Kerpiç Öztürk. Alongside his architectural practice, he taught studio courses at Gebze Technical University, Maltepe University, and Doğuş University. Today, he continues to work in architecture, interior design, and exhibition spaces, and lives in Istanbul with his wife and daughter.