Behind it lies the wealth of a parchment passed from father to son, countless memories, countless witnesses… Standing tall against time with its back to the Bosphorus and its face to the square… We pay homage to a great masterpiece that has served as Istanbul’s showcase for generations and to contemporary Turkish art that has blossomed in its shadow.

What makes it special cannot be limited to its face turned towards Taksim Square. Being Turkey’s only opera house for years is not enough to define it. Its story goes beyond the long project processes, the tragic events it endured, and its resilience in overcoming them, even if it meant falling and rising again with dignity. Nor does identifying it as a symbol of a new national identity suffice. The Atatürk Cultural Centre is a partner in the memories of multiple generations, a meeting point for Turkey’s enlightened face, and a symbol of a city transformed by art in the hands of a father and son over time.

ON A FATHER’S PARCHMENT

Despite the limited means of the Middle Ages, Archimedes’ scrolls are undoubtedly the reason why he survived to this day. Since it was very expensive to produce the animal skin paper on which he wrote his history-shaping notes, the writings were erased, cleaned and prepared to be written again. This method, called palimpsest, stands as a confirmation of the history of the Atatürk Cultural Centre.

Its iconic façade meets digital technologies, artworks integrated with the space are presented in different forms, and it has turned into a cultural space that lives 365 days a year, one step beyond its mission in the 60s. With its libraries, cafes, restaurants, exhibition halls, and spaces for children, Atatürk Cultural Centre seeks to breathe new life into the city while keeping its nostalgic atmosphere intact. But in order to understand its history well, we need to rewind time a bit and remember the story of the Tabanlıoğlu family…

A YOUNG THEATER LOVER

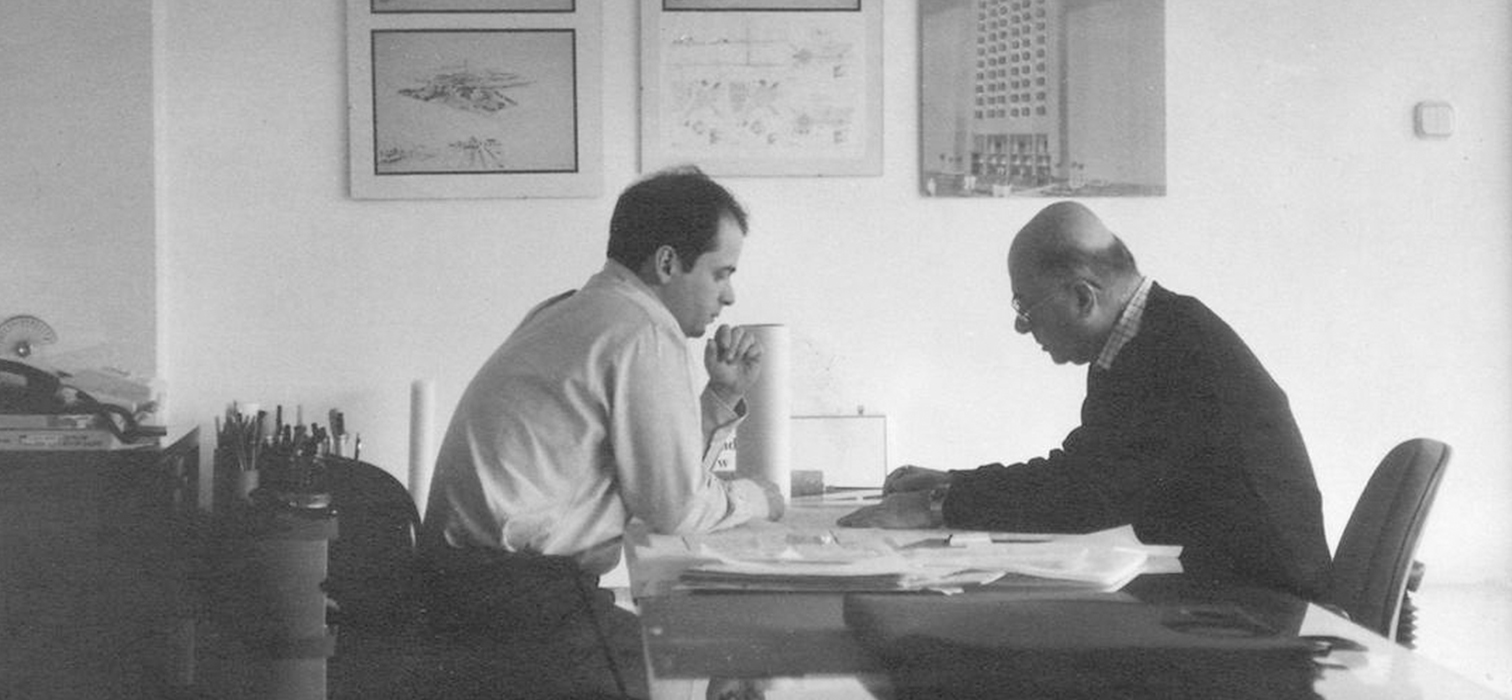

While the world had not yet recovered from the shock of the Second World War, Hayati Tabanlıoğlu, a young and idealistic architect, set off for Europe. Tabanlıoğlu, who took courses at Istanbul Technical University from the doyen names of the architecture world such as Emin Onat and Paul Bonatz, first fell in love with the value of art when he arrived in Europe in 1950. While working in various architectural offices in Germany and Switzerland, he took part in the design processes of important cultural buildings such as Bochum State Theaters and Munich National Theater. He was an idealist, but more than that, he was passionate about theater. While simultaneously working on his doctoral thesis at Hannover Technical University on “The relationship between the audience and the playing space in the theater”, he examined many buildings in Europe and advocated the construction of an opera house in Turkey as a necessity, not a luxury.

While the young architect, not yet in his 30s, was building his future, the foundations of another ideal were being laid in Istanbul. The cultural and artistic momentum rising with the establishment of the Republic had created the need for a grand opera house in Turkey to stage Western arts. This would be an ideological breakthrough, a symbol for the new national identity. In 1939, a project was drawn by French architect Auguste Perret, but it did not advance beyond the design stage. In 1946, the architects Rükneddin Güney and Feridun Kip began to implement Perret’s project, altering it substantially. This time, the economic and political conjuncture of the country did not allow it. No matter how much effort the then Governor and Mayor of Istanbul, Lütfi Kırdar, put into this project, his calculations did not match reality.

The incomplete project was handed over to the Ministry of Public Works and in 1956 Hayati Tabanlıoğlu, known for his work in this field, was appointed to head the project. Tabanlıoğlu did not want to carry the classicist tendencies of the previous architects to the new project. Tabanlıoğlu complained about the technical difficulties and bureaucratic obstacles of working on a ready-made skeleton, and although he said that “the architectural project prevented the architect from unlimited freedom,” he did not give up.

He designed an additional foyer area in front of the facade completed according to the old project. It was at this point that his characteristic touch to the façade facing Taksim Square emerged. This characteristic façade, which he said, “Particular efforts have been made to make this façade unlike any other existing façade in the world, but with a claim to art,” suddenly transformed the neoclassical and heavy air of the Perret project into a transparent, modern expression. When Gerhard Graubner was invited to Turkey to examine the project, the architect, an expert on theater structures, gave full marks to the work of his former student Tabanlıoğlu.

FROM ISTANBUL CULTURAL PALACE TO ATATURK CULTURAL CENTRE

The building opened in 1969 under the name Istanbul Cultural Palace. Despite criticism from the arts community, including Muhsin Ertuğrul, regarding its name, the venue quickly became a favorite not only in Istanbul but also in Europe due to its successful performances. Istanbul now boasted the world’s fourth-largest and Europe’s second-largest opera house.

TRAGEDY STRIKES

Just a year after its opening, during a performance of “The Crucible” in 1970, the building experienced its most tragic event. During the third act, actor Kerim Afşar was preparing for his famous line, “The world is ablaze… We will all burn together,” when flames erupted from the set. The fire, fueled by stage lights, engulfed the building in just 45 minutes, forcing over a thousand people to flee for their lives. Investigations revealed that fire safety systems, including the iron curtain separating the stage from the audience, sprinklers, and even telephones, were inoperative. While some claimed Tabanlıoğlu had repeatedly requested a delay in opening due to incomplete preparations, the investigation focused on sabotage. Ultimately, Tabanlıoğlu was cleared of wrongdoing and reassigned to the project.

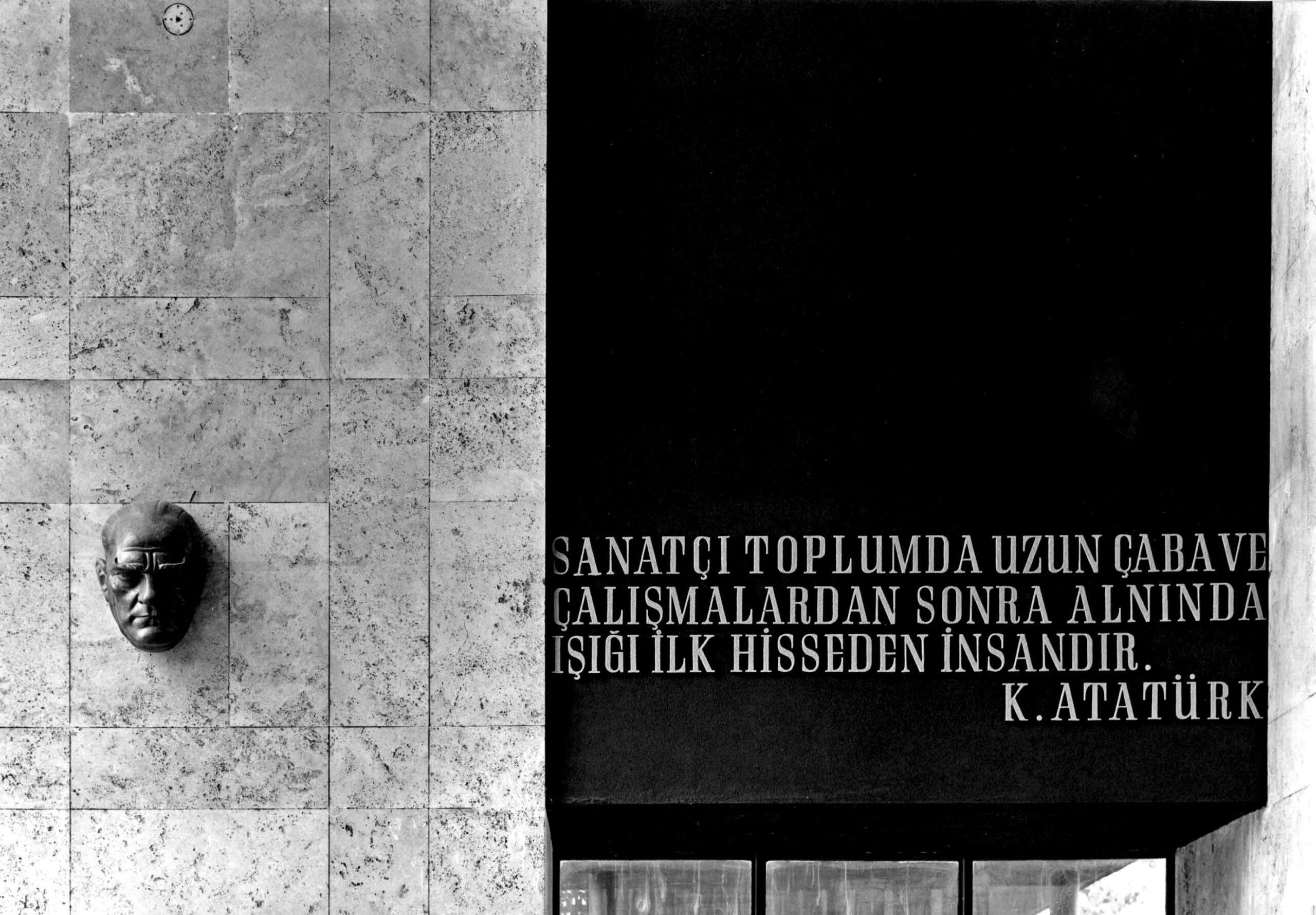

Two days after the fire, journalist Abdi İpekçi wrote in Milliyet newspaper, “What burned was not just a building… The skeleton that remains must be preserved as a painful lesson and a symbol of our negligence.” From that moment, the Istanbul Cultural Palace took on a new meaning in the city’s history. Learning from this tragedy, Tabanlıoğlu rebuilt the structure over seven years, reopening it to the public in 1987 under the name “Atatürk Cultural Centre.”

A RENEWED VISION

The renewed Atatürk Cultural Centre bore the unmistakable mark of its architect, Hayati Tabanlıoğlu. Inside, a staircase adorned with spherical lights that harmonized with the glass façade stood like a sculpture in the foyer. Tabanlıoğlu invited renowned experts of the era, including architect Aydın Boysan, engineer Willi Ehle, lighting designer Johannes Dinnebier, and artists Sadi Diren and Belma Diren, to contribute their expertise. Enhancing the building’s contemporary Turkish art profile were features such as a 100-square-meter Hereke carpet, Cevdet Bilgin’s plastic designs, and paintings by Oya Katoğlu and Mustafa Pilevneli.

Over the years, while the Atatürk Cultural Centre became a cultural landmark, Hayati Tabanlıoğlu passed away, his architectural firm was taken over by his son Murat Tabanlıoğlu, and Turkey faced significant events such as the Marmara earthquake. Structural reinforcement was deemed necessary for the building, but bureaucratic and financial obstacles complicated the process. In 2005, the building was declared economically unsustainable and slated for demolition. Murat Tabanlıoğlu objected, advocating for the preservation of the structure as a cultural heritage site adapted to modern needs.

A NEW BEGINNING

After years of controversy, in 2018, the Atatürk Cultural Centre was demolished. On October 29, 2021, it reopened with a bold vision and an ambitious mission. Designed to transcend the elitist perspective of the previous century, the new building preserved Hayati Tabanlıoğlu’s artistic vision while embracing Murat Tabanlıoğlu’s forward-thinking approach. Resembling the old structure in size and height, it introduced additional functional spaces and a modern aesthetic. A passageway was created in the area once used as a parking lot, iconic digital elements were incorporated into the façade, and its darker tones were updated with light aluminum materials for a more contemporary look. Inside, the spherical lights, striking red surfaces, and iconic staircase paid homage to its predecessor while signaling a fresh chapter.

Some see it as an “unintentional monument,” as described by Austrian art historian Aloïs Riegl, while others view it as fulfilling its intended purpose as a central cultural landmark. Since its inception, the Atatürk Cultural Centre has not only sparked debate within the architectural world but also witnessed societal events and embodied the vision of two generations from the same family. Standing tall with its back to the Bosphorus and its face to the square, it remains a vibrant heart of Turkey’s cultural life.

Credit: Atatürk Cultural Centre – Tabanlioglu Architects

The article was published in Saatolog 2023-24 magazine.

“Istiklal is a Phoenix and It Will Return”: Casa Botter Born-Again